Jan 24, 2024

Russia’s War Fuels a Wage Spiral That Threatens Army Recruitment

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Russia’s war in Ukraine is intensifying an acute deficit of workers that’s hitting businesses from metal refineries to posh Moscow restaurants and igniting a race to increase salaries that threatens the Kremlin’s ability to replenish the armed forces.

The competition for employees has pushed wages up at a double-digit pace and made once-relatively lucrative military service less appealing, even after a 10.5% increase in monthly pay to fight in the war last year. Specialists such as engineers, mechanics, machine operators, welders, drivers and couriers can now find jobs with salaries comparable to or greater than in roles with the army after compensation for such work rose by 8%-20% last year, according to data from local recruitment service Superjob seen by Bloomberg.

For a period after Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered a mobilization in 2022 for the war, companies lost employees to the army and defense plants, which offered much higher wages than even the most generous civilian factories. Then, private sector salaries began to rise in response, and many companies regained their competitiveness.

Now, there’s competition within civilian sectors. Industrial facilities vie for workers as openings for couriers and security guards offer top salaries that match those in factories, but with far fewer job-related responsibilities, a top executive at one of the biggest metals and mining companies said, asking not to be identified because he’s not authorized to speak to the media. The result is that today’s labor shortage is unlike any seen before, he said.

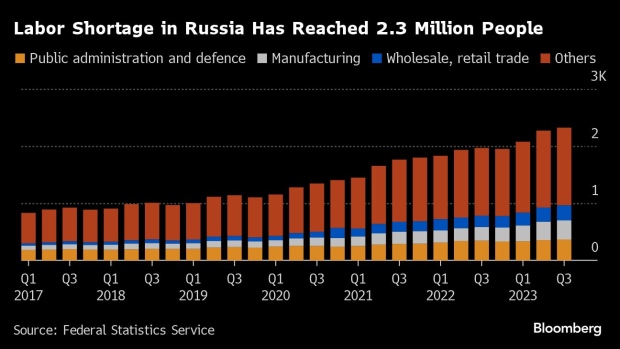

The Russian economy needs a record 2.3 million workers, Federal Statistics Service data published at the end of December show. At the same time, Russia’s unemployment has plunged to a historical low of 2.9%.

What Bloomberg Economics says...

“Russia’s strategy of recruiting armed forces volunteers with outsized sign-up bonuses and large pay was likely designed for a short conflict. As the war drags on, labor scarcity and low unemployment has meant private employers have few options but matching what the military offers.

As market wages catch up to military pay, Russia will be pressed to choose between shifting an even larger share of its public spending toward the military, accepting a drop in volunteer inflows or leaning more heavily into targeted mobilization.”

Alex Isakov, Russia economist

The sectors that have the greatest need for new personnel — public administration and defense — had a deficit of 365,000 workers. The Kremlin still mostly relies on volunteers to fight its war in Ukraine, offering 210,000 rubles monthly.

It’s eager to avoid any new mobilization ahead of presidential elections in March, where Putin is all but certain to win his fifth term in office, after the last one in September 2022 sparked a sharp increase in public anxiety about the war in opinion polls.

Putin’s decision then to call up 300,000 reservists triggered an exodus of hundreds of thousands of Russians eager to avoid the war. Many were young professionals, whose departure further exacerbated strains in the labor market.

In 2023, about 490,000 people were serving in the army under contract, according to Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu. The military receives more than 1,500 applications to the service every week, he said.

The labor shortage has become a major headache for the central bank, which doubled the key interest rate last year in part because of the inflation stemming from rising wages. Meanwhile, the scarcity of workers is acting as a limit on the Russian economy’s potential growth.

In addition to the difficulty of filling positions, salaries are eating into firms’ profits. On top of wages, manufacturers now offer additional benefits to attract and retain employees.

One Russian steel major, Severstal, is set to spend 9 billion rubles ($103 million) on salary increases in 2024 and 15 billion rubles for its employee support programs, which covers expenses for things like sports and mortgages, its press service said.

In Demand

Restaurants and construction companies are also feeling the squeeze as migrant laborers from neighboring countries leave Russia because high inflation and the weak ruble have lowered their income in dollar terms. Chefs are “in great demand,” according to Igor Bukharov, head of the Federation of Restaurateurs and Hoteliers, who said their salaries had increased by 10%-15%, to sometimes as much as 300,000 rubles.

The labor shortage has forced Russia to seek workers from further afield. About 10,000 people are set to arrive from Kenya after Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov visited Nairobi in May for the first time in 13 years, the state-run Tass news service reported, citing the Kenyan president’s spokesman, Hussein Mohamed.

Authorities in one Siberian region are counting on North Korea as a source of workers for their construction sites, which lack thousands of builders, while the head of the National Association of Developers Anton Glushkov wants to attract “excess” labor from Cuba.

Still other firms are looking to mine less conventional domestic sources for labor. At the end of last year, Russian Railways JSC Deputy Managing Director Dmitry Shakhanov said the company is planning to hire convicts sentenced to forced labor and has already started negotiations with the Federal Penitentiary Service.

According to Superjob’s research, the Russian labor market’s new reality is one where 85% of companies in Russia are experiencing staff shortages and 93% dare not reduce staff, and all while the number of job postings surged by 1.5 times in 2023.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.