Jul 8, 2022

Stock Faithful Revive Prayers That All the Bad News Is Priced In

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The bounce is back in equities. Could they have fallen enough to account for what comes next in the economy? While the consensus of the pundit class is no, investors are again showing signs of seeing it otherwise

Deluded as they have repeatedly proved, hopes that the worst is over are resurfacing. The S&P 500 just shook off rising bond yields and climbed for the week, at one point stringing together the longest streak of gains since March. Notably, bulls are flexing on the eve of a period when companies will give details on the topic dearest to investor hearts: the state of earnings.

Everyone has an opinion of how bad corporate profits will be -- including the market. The S&P 500’s $12 trillion slide this year is nothing if not a frantic exercise in figuring out how companies will do in 2023. One back-of-the-envelope methodology suggests traders would be comfortable with earnings coming in 16% below what analysts currently expect.

While that may prove optimistic, it’s a reminder to the bear camp that this year’s violent repricing in stocks has created at least the beginnings of a cushion for when Federal Reserve rate hikes start to bite.

“Some element of the earnings compression has been priced in. Probably not all of the risk there, but that’s probably not crazy,” said Matt Benkendorf, chief investment officer at Vontobel Quality Growth Boutique. “The market gets quite scrambled when it has to digest a few exogenous things at once.”

There’s been a lot to digest. Friday’s stronger-than-expected jobs report fueled concern than the Fed will have to toughen its hawkish stance to cool a hot labor market, a move that might drag the economy into a recession. Yields on two-year Treasuries surpassed 10-year’s for four straight days in the longest run of inversion since 2019.

Among market skeptics, few things come up for greater ridicule than existing Wall Street estimates for earnings. Estimates that S&P 500 profit growth will average around 10% over the next three years -- a prediction that has barely budged as the Fed withdrew stimulus -- are routinely mocked as a fantasy, sure to plunge. How far they will fall is arguably the biggest question in the stock market. What does the market itself have to say on the topic?

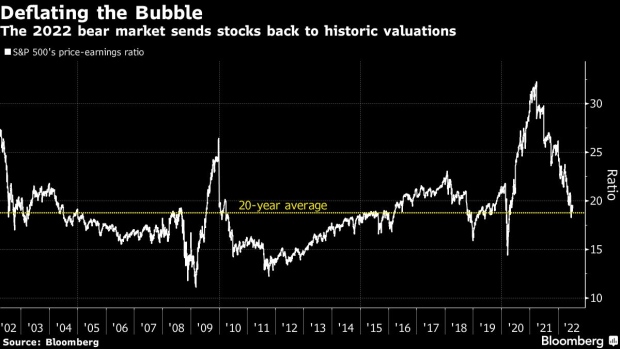

Down as much as 24% in 2022, the S&P 500 has traded as low as 15 times analysts forecasts for next year’s earnings, currently $246.10 a share. One way of deciphering how much traders really think companies will earn in 2023 is to apply a historical multiple to the index and see what pops out on the profit line. Right now, by dividing the S&P 500’s price of 3,899.38 by a historical P/E of 18.8, the market can be framed as seeing 2023 earnings of about $207 a share. That is, 16% below where analysts peg them now.

“There was all the talk about, ‘hey, it’s just been a multiple contraction bear market with interest rates up and therefore equity numbers should come down,’ and they have,” said Michael Vogelzang, chief investment officer at CAPTRUST. “What we don’t know is how much of that 20% drop is associated with an earnings shortfall that may be coming up in the next couple of months or next couple of weeks.”

To be sure, things can get much worse should a recession unfold in 2023, according to Credit Suisse Group AG strategists led by Andrew Garthwaite. In what they call a “gray sky scenario,” earnings estimates could be slashed by about 20% to $200 a share and the S&P 500 drop to 3,200. That’d represent an 18% decline from the index’s close Friday.

“Markets tend to trough four months before the trough in earnings and earnings downgrade cycles tend to last 19 months,” the strategists wrote in a note. “This would imply market lows in 2023.”

That caution is shared by Scott Opsal, director of research & equities for Leuthold Group, who studied earnings cycles since 1995 and found that the market typically wasn’t bothered until analyst sentiment began to sour. In all four instances where profit estimates started big declines, the S&P 500 posted positive returns during the six months heading into the top.

Then when analyst downgrades started, stocks fell along with them, particularly in recent bear markets. In the dot-com crash, they lost almost a quarter of their value following peak estimates in August 2000, and in the financial crisis, the S&P 500 plummeted nearly 40% after the earnings high-water mark in November 2007.

While that could still happen in this bear market, it’s notable how much pain has already been endured by stock owners while earnings are still rising. Rather than wait for proof, it might be argued, investors have taken the repricing into their own hands.

Not so fast, says Opsal. Unlike 2008 and even 2000, when market excesses were concentrated in tech, this year’s rout has landed in a market that was broadly overvalued. While losses to date have shrunken those, more pain awaits as earnings estimates come down.

“The valuation exuberance has been taken out and I would say that valuations today are pretty fair and not very scary looking,” Opsal said. “The problem now is, if the economy weakens to the point where earnings go down, I don’t think we’ve priced enough of that in.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.