Jun 29, 2020

Suitcases of Cash Halted by Virus in EU Money-Laundering Hotspot

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- When customs agents in Riga followed a tip and searched passengers arriving on a private jet from Ukraine last year, they hit the jackpot. Luggage belonging to the four travelers contained about $1 million in U.S. and European banknotes. The contraband was seized.

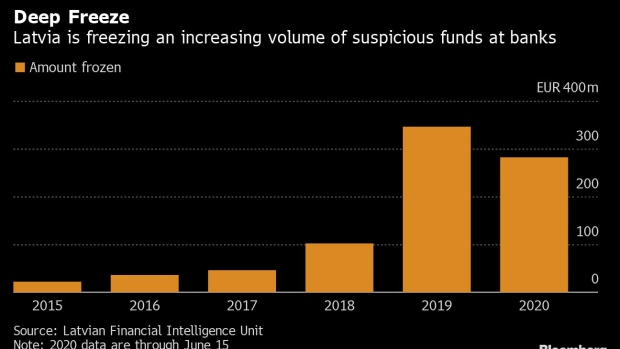

Latvia, a European Union and euro-area country of just 1.9 million people, hit the headlines in recent years for the piles of dirty money sloshing around its banks. A crackdown has ended much of the illegal activity -- often wire transfers from clients in the former Soviet Union looking for a gateway for funds into the EU. Some more old-fashioned methods of moving money persist, however.

Based on deposits by commercial lenders at the central bank, Latvia had thought that about 400 million euros ($450 million) was being smuggled in each year. Recent border closures to curb the spread of Covid-19 are confirming those suspicions.

“Suddenly, there wasn’t this cash,” Ilze Znotina, who heads the financial intelligence unit, said in an interview in the Baltic nation’s capital.

She talks of people sending money via payment companies to neighboring countries, then withdrawing large sums at ATMs near the border and bringing it to Latvia -- often to dodge taxes on employees’ salaries.

Elsewhere, law enforcement is keeping tabs on people arriving and departing as often as 15 times a year, sometimes with their entire families in tow -- including children. Each carries an amount just short of the 10,000-euro threshold for declaration. The money is probably then deposited and transferred on to another country.

Commenting on the seizure at Riga airport, Znotina said investigators established that one of the passengers was a businessman who owned banks both in Ukraine and Latvia. “The question, then, is why do you need to bring cash?”

Latvia and Estonia, next door, have in recent years been at the center of dirty-money storms that sparked the demise of several local lenders and uncovered violations at the likes of Danske Bank A/S and Swedbank AB. Latvia, which at one point handled as much as 1% of the world’s U.S. dollar transactions, has since reined in foreign deposits and questionable offshore dealings. This year, it avoided inclusion on a list of jurisdictions that have failed to punish money launderers.

The country emerged as a financial hub as communism began to collapse and has a history of shipping cash by air.

In the early 1990s, Soviet TU-134 cargo planes filled with banknotes would fly to Russian regions on behalf of Parex, a foreign-exchange trader that went on to become a major bank, according to the autobiography of one of its founders. The book also describes cash belonging to a powerful Kazakh citizen arriving in Latvia and being driven down a road lined with armed guards.

Three decades on, “cash is still one of the biggest problems,” according to Znotina, who wants increased scrutiny of trains, road vehicles and people crossing the border on foot. A prevalence of 500-euro notes handed to the central bank by commercial lenders is a red flag for criminal activity, she said.

The help provided by the coronavirus pandemic is likely to be short-lived, however, with European nations gradually reopening their borders in to save the summer tourist season. The new influx of visitors will test the authorities’ tougher stance on illicit cash.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.