Mar 12, 2021

The economy looks set to roar, and that worries investors

, Bloomberg News

McCreath: The quality of the market move higher in Canada isn't as good as in the U.S.

Before we talk about what’s going on in the stock market—and why it’s whipsawed so many investors even though the S&P 500 index is near a record high—we have to talk about bonds.

U.S. Treasuries are probably the world’s most important financial market, but it’s easy to forget about them when they’re well-behaved. When prices suddenly drop, which causes their yields to rise, for many professional investors it can seem like Godzilla poking his head above water off the coastline: Time to run and hide—trouble may be coming.

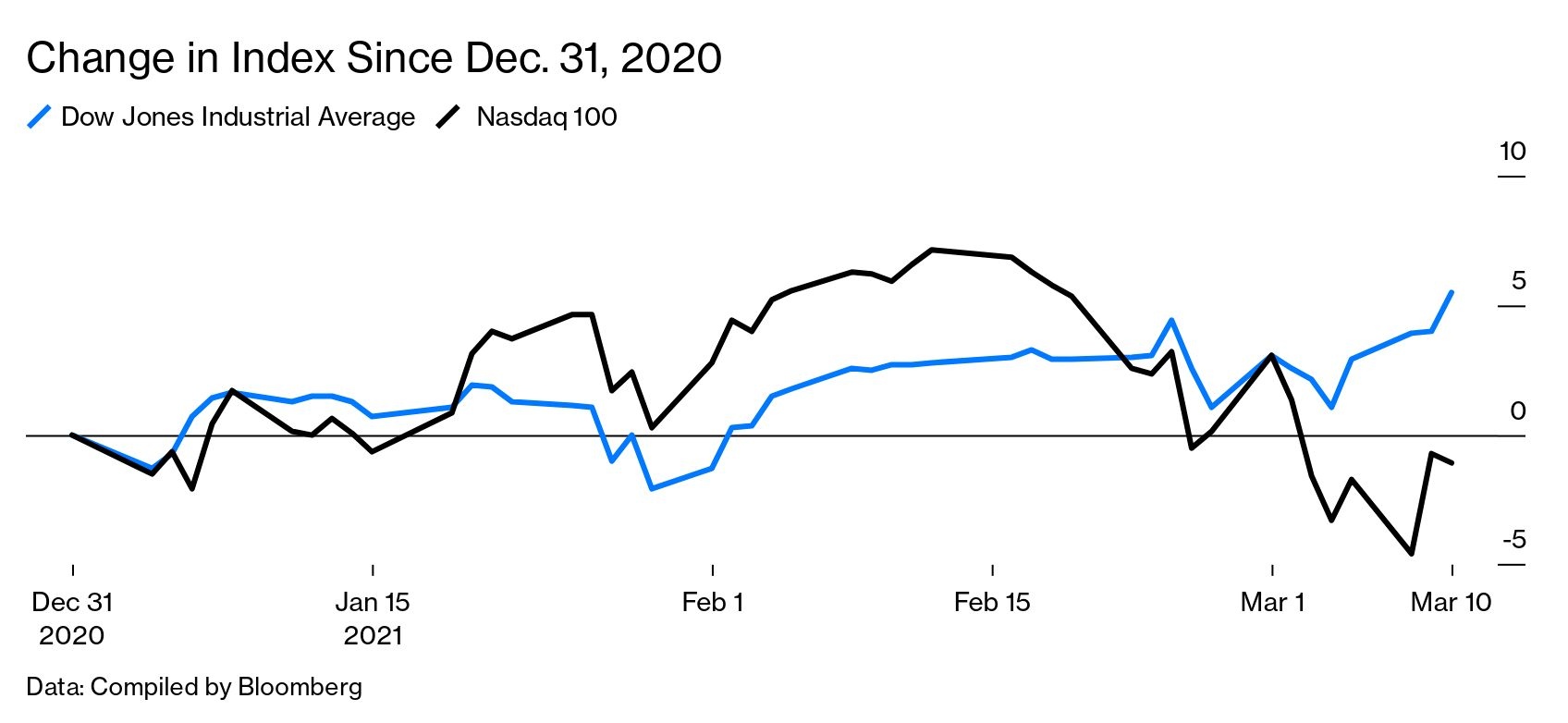

The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury climbed this month to as high as 1.62 per cent, up from less than 1 per cent at the start of the year. That’s still very low by historical standards, but it was high enough to spread pain in the most popular and rewarding parts of the stock market. The Nasdaq 100 Index, which is dominated by the likes of Amazon.com, Apple, and Microsoft, fell as much as 11 per cent from Feb. 12 before rebounding in recent days as the bond market selloff subsided. Cathie Wood’s ARK Innovation ETF, which surged 153 per cent last year and attracted more than $15 billion in cash in 14 months, plunged almost 30 per cent and then climbed back part of the way. Likewise, Tesla tumbled and so did special purpose acquisition companies.

Why would a bond yield spike have that kind of effect on high-flying tech stocks? Partly because of the role Treasury yields have in setting the so-called risk-free rate, a yardstick against which other investments are measured. When a safe Treasury delivers a scant 1 per cent per year, investors may be willing to pay up for speculative assets to get a higher return. The increase in bond yields changed the math, making stocks look relatively more expensive. It didn’t help that valuations of Nasdaq 100 stocks were already high because investors had piled into tech-driven companies during the pandemic, betting that the lockdowns would be good for revenue from online shopping and streaming services.

“It feels like an attitude adjustment for tech and growth stocks,” Mike Bailey, director of research at FBB Capital Partners, told Bloomberg News. “Investors have decided that these Covid winners just got too expensive, and now it’s time for a valuation haircut.”

The yield on Treasuries also plays an outsize role in influencing interest rates on everything from mortgages to corporate debt. And because innovation and disruption are often brought about with borrowed money, higher rates can be bad news for companies with big plans that need to raise money to make them happen.

But perhaps most important is what the rise in yields signifies to markets: an economy poised for a major growth spurt as more people get vaccinated. Wait—that’s supposed to be a good thing, right? It absolutely is, but markets and the economy don’t run on the same timeline. That was clear as stocks surged despite mounting Covid-19 deaths and waves of unemployment and business closures. Now bond investors see consumers with swollen savings getting ready to spend again while companies rehire, and to them that looks risky. A hotter economy could mean inflation and rising interest rates, which can hurt bondholders. So investors drive up yields to give themselves a buffer.

Equity investors, meanwhile, start rethinking their picks. Expensive growth stocks may not look as attractive when you can make decent profits in any business that can ride a reviving economy. Stocks in the energy, financial, and industrial sectors have been doing just fine recently, and so-called value stocks with modest prices have seen a long-awaited revival. The Dow Jones Industrial Average—which includes traditional businesses sensitive to the economy such as American Express, Caterpillar, and Chevron—is up 5.5 per cent this year, while the Nasdaq 100 is slightly down.

What happens next hinges not only on the continued vaccine rollout and effectiveness of President Biden’s $1.9 trillion relief package, but also on the delicate back-and-forth between U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell and the markets. The spike in 10-year yields suggests that efforts to revive the economy are working, but if those rates rise too quickly, there’s a risk they’ll nip the recovery in the bud.

The Fed has signaled that it will likely keep monetary policy accommodative for years to fight the pandemic’s long-term damage. In his recent public remarks, Powell has acknowledged that the rise in yields had caught his attention, but he stressed that overall financial conditions are more important. He also said he would be concerned if the yield rise was accompanied by disorderly conditions in markets.

The latest gyrations in tech stocks don’t qualify as disorder. With many investors warning that equities are still in bubble territory, and the Fed serving as the usual suspect for getting them there, some minor hits to richly valued stocks might be welcomed by Powell. He and his predecessor, Janet Yellen—now the U.S. Treasury secretary—both indicated some wariness last month about exuberant markets. Policymakers face a dilemma: While they recognize that loose policies can fuel financial excess, they believe the virus-damaged economy still needs substantial help.

Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, anticipates that the rise in yields will take some froth out of the equity and housing markets. That could reduce the risk of a harder landing later on. “I would see that as a positive thing,” he says. “It’s reducing the risk that bubbles develop to the point where they become existential to the recovery.” —With Claire Ballentine