Nov 14, 2022

US Treasury Has Scope to Avoid Debt Ceiling Gimmicks Entirely

, Bloomberg News

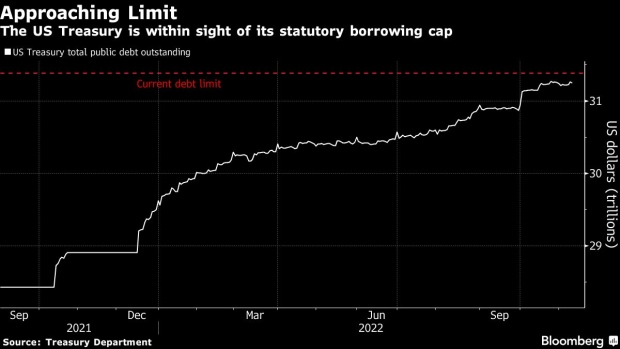

(Bloomberg) -- There’s a chance that the US Treasury can escape the usual market-distorting gimmicks it’s historically needed to avoid breaching the government’s statutory debt ceiling -- if the politicians in Washington can actually get their act together soon enough.

In previous legislative battles around passing laws to increase the government’s borrowing limit -- the most recent being in late 2021 -- the Treasury has usually been forced to employ a range of so-called extraordinary budgetary measures to keep under the cap. These include things like not making contributions to certain government pension funds and drawing down its cash pile to uncomfortable levels, which have tended to extend the Treasury’s borrowing authority by several hundred billion dollars and push back the deadline for technical default risks.

With the present limit of $31.38 trillion soon heaving into view, market experts and officials are busy weighing when these kind of fiscal gymnastics might start to begin. And some are hopeful that the ultimate answer may be not at all, if Congress can act soon enough.

Key Democratic Party leaders including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen have all signaled that they’re keen to extend the limit by the end of this year, during the so-called lame duck session before the newly elected Congress takes over. With votes still being counted for a number of close-fought districts, it’s not yet clear who will control the lower house, but there is a good chance it will be the Republicans and passing a bill through the current Congress would mean avoiding a protracted and possibly damaging fight next year.

Congress could, of course, choose to leave this imbroglio until next year. The extraordinary measures that the Treasury has available to it could stretch the deadline for a solution into the second half of 2023. But that has a political cost for Democrats, with Republicans saying they plan to use the debt-limit deadline to extract concessions on spending and government programs. And it has costs for the market: the fiscal limbo dance of extraordinary measures creates potential distortions as the Treasury’s cash pile shrinks and bill issuance dwindles.

“It now appears likely that it won’t need to begin playing accounting games until December 15 at the earliest,” Wrightson ICAP economist Lou Crandall wrote in a note to clients. “That may be late enough in the month to persuade the Treasury to pursue normal cash management policies in the near term.”

As of last week, the Treasury still had about $205 billion of room under the current ceiling, which suggests the department has about a month before it invokes extraordinary measures, more time than Wrightson had previously anticipated. With a little more room to maneuver in the near term, the Treasury could actually increase the size of some of its bill auctions within the next two or three weeks in order to keep the department’s cash balance on track for its end-December goal of $700 billion, according to Crandall.

Of course, whether the Treasury can avoid gimmicks after that depends upon Pelosi, Schumer and Co. can actually get a ceiling deal done.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.