Mar 29, 2023

Wall Street Has No Idea How to Price In Banking Upheaval

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Struggling to figure out what all the financial stress means to markets? So are professional forecasters.

As fast and furious as the news has come, the reaction among stock strategists and earnings analysts has been uniform: no reaction. Whether unwilling to commit to a new course, unable to formulate a new thesis — or simply unconvinced anything important has happened — estimates remain almost exactly where they were before all the action erupted.

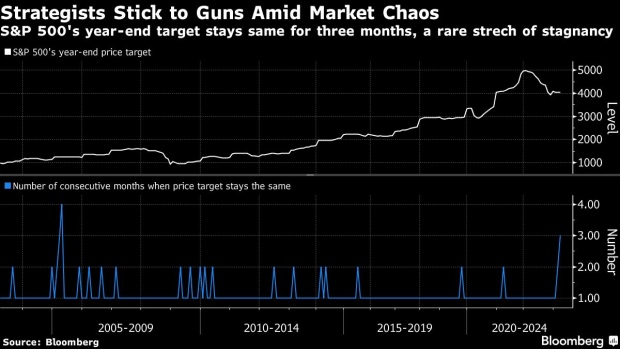

The stasis is most apparent among Wall Street strategists who predict markets based on macroeconomic trends. For a third straight month, their average year-end target for the S&P 500 stayed at 4,050, a streak of inaction not seen since 2005.

While frameable as conviction, the stillness more likely reflects confusion as to where the economy and market are heading. Arguing for the latter is the gap between the highest and lowest year-end targets for the S&P 500: at 47%, it’s the widest at this time of year in two decades, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

“It’s a slow-motion series of events with unknowable outcomes,” said Michael Purves, founder of Tallbacken Capital Advisors. “We do not know how contagious this regional bank crisis is. We do not know the government response to an acceleration. And if we get a seize-up in lending, it is unclear to what magnitude that hits earnings.”

The lack of reaction contrasts with big money managers who quickly adjusted positions after the banking turmoil. Equity-focused long/short hedge funds have dumped financial shares and sought safety in technology megacaps, while trend-following funds unwound some positions after being caught out by cross-asset volatility, according to data compiled by Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s trading desk.

As things stand now, net equity exposure at hedge funds has remained low in the 19th percentile of a one-year range, cash holdings at mutual funds have risen for 15 straight months, and so-called commodity trading advisers have gone from being long around $130 billion of futures to being short around $28 billion, the firm’s data show.

“It’s felt like most investor cohorts have had a rough couple of weeks,” Bobby Molavi, a managing director at Goldman, wrote in a note. “There remains a lack of conviction almost everywhere but at least positioning matches sentiment for the arguably the first time this year.”

To be sure, sitting still has been profitable of late. The S&P 500 is coming off a second straight week of gains, almost erasing its entire loss from March 8, the day before the plunge in regional banks. While Treasuries have dealt body blows to short sellers, holding on through the worst volatility in four decades would’ve produced sizable profits.

For now, traders are unwilling to push the market in any direction. The S&P 500 on Tuesday was trapped in a 0.7% band, the narrowest intraday range since November. Futures rose 0.8% as of 8 a.m. in New York.

With so much hanging in the balance, conflicting narratives abound. While the banking crisis could lead to tighter lending standards that hurt the economy, the specter of a recession means the Federal Reserve may be close to done with its aggressive inflation-fighting campaign.

Analysts following individual stocks have barely changed their outlooks on corporate earnings. Their aggregate 2023 forecast for the S&P 500’s members has stood near $220 a share from the week before the failure of lenders including Silicon Valley Bank.

With first-quarter earnings set to start in about two weeks, it’s possible that many of them are waiting for guidance from company management before adjusting their numbers.

“The US economy and labor markets have been remarkably resilient over the last nine months, and markets have extrapolated this to mean corporate earnings can remain strong as well,” said Nicholas Colas, co-founder of DataTrek Research. “Q1 earnings reports and management guidance, which we will get in the first half of Q2, will test that theory.”

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.