Jul 12, 2023

Why Private Equity Is Chasing Plumbers and Lumber Yards

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Local plumbers and lumber-yard owners across the US are feeling a bit like tech entrepreneurs of late — juggling multiple offers from private equity-backed firms that increasingly are targeting mom-and-pop businesses.

Wall Street has been buying into fragmented Main Street industries for years, with dental and veterinary practices among the favorite targets. It’s known as the roll-up strategy – and it’s catching a tailwind right now, and expanding rapidly in household services and building materials.

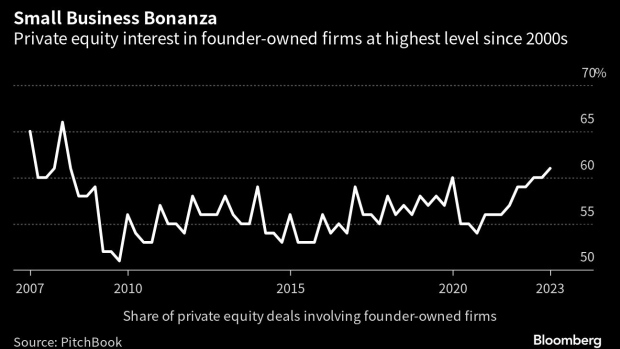

Small firms account for the biggest share of acquisitions by PE funds and their portfolio companies since the late 2000s, according to data from industry analyst PitchBook. They made up more than 61% of all private equity deals in the first quarter of 2023, compared with an average in the mid-50s over the past decade or so.

“If you acquire enough, you get economies of scale,” says Tim Clarke, PitchBook’s lead private equity analyst. “You just keep rolling rolling, rolling and before you know it you’ve got 10-20% of the market.”

‘They’re a Nuisance’

One reason that approach is popular now, according to Clarke, is that higher interest rates have pushed valuations down across the board. Owners who might otherwise have considered a sale — whether they’re publicly traded companies, or private equity — are holding onto companies in their portfolios instead. As a result, would-be buyers are turning toward smaller privately-owned firms, which also tend to be cheaper relative to their earnings.

What’s more, private equity’s enthusiasm for small firms is spreading into industries like plumbing and other trades — which have shown they’re recession-proof, even in the Covid slump, and have room for consolidation because markets are typically divided up among many businesses.

All of this Wall Street interest is a blessing for some Main Street owners looking to cash out. They don’t all see it that way, though.

In the Atlanta area, Jay Cunningham says he gets several pitches a week from PE-backed firms wanting to buy his Superior Plumbing — one of the few sizeable local firms that hasn’t already been snapped up by investors — or from investment bankers wanting to bring Superior to market. He’s not interested.

“I probably think they’re a nuisance as a whole,” Cunningham says.

In terms of dollar value, PE acquisitions of publicly traded companies or those bought from other private equity firms still make up the biggest chunk of deals. Even by that measure, though, purchases of founder-owned businesses — which in most cases are valued at under $100 million apiece — are on the rise. They accounted for more than 43% of deal value in the first quarter of 2023, well above the typical levels in recent years, according to PitchBook.

‘Lot of Players’

Especially prized are firms with steady revenue, subscription models and electronic billing, says John Wagner, a New Mexico-based investment banker who helps small and midsize companies find buyers. Better yet, he says, is a locally owned firm with strong revenue but high expenses — an opportunity to cut costs, increase efficiency and quickly boost the firm’s value.

In the Denver area, Steve Swinney is constantly hunting for lumber yards, steel fabricators, drywall distributors and kitchen-interior companies. His Kodiak Building Partners started out buying one steel fabrication firm 12 years ago, in the wake of the Great Recession. It’s made about 40 acquisitions since then, and welded them all into a building-materials firm with sales of around $3 billion.

As it looks for more mom-and-pop firms to buy, Kodiak — which is majority owned by New York-based PE firm Court Square Capital Management — faces plenty of competition.

“There’s definitely a lot of other players out there,” Swinney says. “I wish we were alone.”

John Loud gets as many as 30 solicitations a month for his Kennesaw, Georgia-based alarm installation firm, Loud Security Systems, which has about 60 employees and more than $7 million in annual revenue.

“It’s a non-stop barrage,” Loud says, and it’s been going on for years. He used to joke with employees: “If you want job security, save me from these calls and these emails.”

Open to Offers

Nowadays, though, Loud is entertaining offers. His two kids aren’t interested in running the family business, and at 56 he feels closer to the end of his career than the start.

He expects to continue with the firm after any sale, and keep 30% equity in the company, but figures his proceeds will be enough that if things don’t work out, “I’ll never have to go create a new business, never have to go to work.”

His longtime friend Cunningham, the Atlanta-area plumber, is comfortable for now holding onto Superior Plumbing, which has about 60 employees and $10 million to $15 million in annual revenue.

A couple years ago, the 61-year-old Cunningham says, he sent a rudimentary financial brief to an investment firm and the would-buyer shot back an offer for more than $60 million. But unlike many peers, his children are interested in taking over the firm at some point.

“Right now I have five kids in my business. That’s a combined north of 60 years of time,” Cunningham says. “If I sold for $60 million, it wouldn’t enrich my life at all.”

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.