Nov 8, 2023

Why Those Bank Emissions Numbers Are So Rosy

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

On the surface, Deutsche Bank AG, Citigroup Inc. and Mizuho Financial Group Inc. all appear to be delivering on their promises to cut carbon emissions.

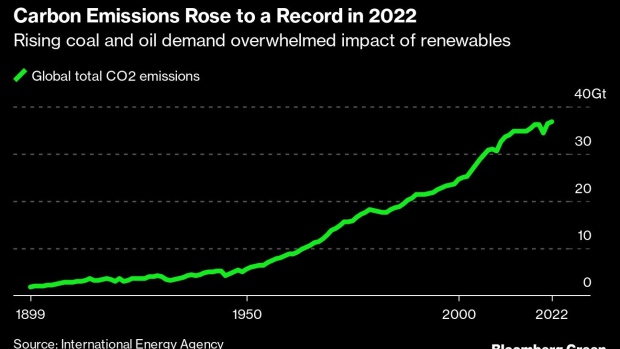

The three banks (along with most of their peers) have committed to eliminating financed emissions—the greenhouse gas-pollution enabled by their lending and investing—starting with the most carbon-intensive areas of their balance sheets. And in sustainability reports published this year, all three banks said those numbers had come down—in some cases significantly.

Yet if you read the footnotes, one would discover that their emissions have fallen in large part due to technical factors outside of their control.

Just last month, Deutsche Bank reported that emissions associated with its lending to oil and gas companies—the primary perpetrators of global warming—declined 29% from the prior year. As a result, the bank is much closer to its 2030 target for reducing financed emissions from the sector.

How did this happen? The war in Ukraine may have played a part. The German lender said the reduction was “predominantly explained” by three factors, the biggest of which being a decrease in the size of its loan books after ending relationships with Russian clients. But additional factors were changes in exchange rates and the increasing market value of its fossil-fuel clients.

Deutsche Bank, along with most other banks, calculates financed emissions numbers using methodologies developed by the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF). That methodology requires banks to account for a portion of the annual emissions of the companies they lend to, and then calculate a so-called attribution factor for each loan.

That math represents the ratio between the outstanding amount of the borrowing (the numerator) and the value of the company being financed (the denominator). The latter is expressed as the EVIC, or enterprise value including cash of the respective client.

With higher energy prices pushing up valuations of fossil-fuel companies (the denominator in the above calculation), banks appear to be doing less damage since their financing (the numerator) stays the same. The US nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund writes in a report entitled Carbon Conundrum, that this “means a bank’s share of the client’s emissions can decline even though financing to the client didn’t change.”

Jörg Eigendorf, Deutsche Bank’s chief sustainability officer, concedes that the calculation behind financed emissions “certainly needs more work to make it better—but it is the best indicator we have right now and helps us tremendously to manage our carbon budget.”

Eigendorf said the lender has been transparent in explaining the reasons for movements in its emissions numbers. “The key source of uncertainty” in financed emissions disclosures comes not from EVICs but rather from the swath of proxy data that is used to estimate emissions for companies that don’t disclose them, he says.

When Citigroup reported its latest financed-emissions numbers in March, the bank sounded a similar note, saying in a report that “a number of important variables create year-to-year volatility in reported figures and distort meaningful analyses of client decarbonization progress.”

Citigroup reported that a “data mismatch,” where energy companies ended 2021 with higher valuations following a year of decreased production and emissions, resulted in lower reported financed emissions figures. The company has yet to publish its 2022 financed-emissions data.

“We shouldn’t expect that emissions data will immediately show a straight line from our current energy system to a decarbonized one,” said Val Smith, the bank’s chief sustainability officer. “We expect that emissions data will continue to improve as we move along that pathway.”

Japan’s Mizuho reported a 29% decline in absolute emissions from its oil and gas clients in 2021 relative to 2019 baseline levels. The drop was largely tied to production declines caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and “a reduction in Mizuho’s loan share as a percentage of corporate value associated with an increase in the market capitalization.”

A spokesperson for Mizuho said “financed emissions alone may not adequately evaluate the efforts of companies and financial institutions towards transitions.” As such, “complementary metrics” may be required, such as data provided by clients on their transition readiness.

The PCAF methodology, which has quickly become the industry standard, was agreed upon in late 2020. A year later, the Net Zero Banking Alliance was formed, prompting most major Western banks to commit to reducing their financed emissions.

This is all a relatively new discipline, so “investors shouldn’t take portfolio-level financed emissions at face value,” said Xinxin Wang, executive director for environmental, social and governance and climate solutions research at MSCI Inc.

Other banks, including Credit Agricole SA to Royal Bank of Canada, have pointed out the inherent volatility of the numbers due to the use of EVIC in the calculation methodology. There’s now a growing discussion about how to supplement or adjust EVIC.

PCAF said companies that report financed emissions using its methodology can apply “corrections” to the EVIC calculation to avoid fluctuations in market prices, though it warned that inconsistent approaches to these adjustments may reduce the comparability of results between different firms.

In a statement, Angélica Afanador, executive director of PCAF, noted that “financial institutions can choose to describe the meaning of the numbers and the cause behind changing emissions year on year.”

But even with all the concerns about accuracy, financed emissions remain the key metric by which external stakeholders can measure banks’ progress on their climate commitments. And until something better comes along, investors will need to learn how to read a financed-emissions disclosure.

Just be sure to remember that those findings may not be as promising as they first appear.

Sustainable finance in brief

Much of the fossil fuel industry may be facing an era of credit downgrades if producers prove too slow to adapt to a low-carbon future, according to Fitch Ratings. Oil and gas companies stand out as the most vulnerable issuers in an analysis by the ratings company, which sought to gauge how businesses will cope with climate risks such as increasingly stringent emissions regulations. Fitch’s models show that more than a fifth of global corporates across regions and sectors face a material risk of a ratings downgrade due to an “elevated” level of climate vulnerability over the coming decade. Half of those issuers are in the oil and gas industry.

- Bankers servicing one of the world’s biggest ESG debt markets are seeking legal protections to guard against future greenwashing claims.

- The Credit Suisse executive who built a hot ESG debt-swap market has secured a senior role within UBS Group.

- Welcome to Trump country, where US President Joe Biden helped create 700 new green jobs in a solar factory.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.