May 23, 2022

Australia Voted for Climate Action. Here’s How Elections Impact Carbon Cuts

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

Targeted political contributions are a more effective climate pollution-fighting tool than buying voluntary carbon offsets, even valid ones. That’s the qualified conclusion of three researchers who last year introduced the notion of voluntary “political carbon offsetting” in a thought experiment that estimates the greenhouse-gas implications of voting and campaign donations.

After a weekend when voters in Australia, tired of inaction on climate, ousted the conservative coalition government in favor of a Labor Party that is aiming for deeper emissions cuts, the 2021 paper is well worth revisiting.

“I find it a little frustrating that if I want to know how much emissions I save if I go from an internal combustion vehicle to an electric vehicle, I can totally find that out,” said Seth Wynes, lead author of the paper and a postdoctoral researcher in climate change mitigation at Concordia University in Canada. It’s the same for more efficient refrigerators and eating vegan. But “what if I vote for this candidate? We have no idea. It’s disappointing that no one had ever tried to measure it,” Wynes said.

There is no carbon equation for voting in the way that a gallon of gasoline plus oxygen and spark plugs = 20 pounds (9 kilograms) of CO₂. But the authors do reason their way to CO₂ estimates implied in casting a vote.

The authors looked at the 2019 Canadian elections, in part because the parties were clearly divided on climate. The Conservative Party of Canada wanted to reverse the nation’s carbon tax and enact other policies opposed by climate experts. The Liberal Party, which won, and three others promoted policies expected to cut emissions.

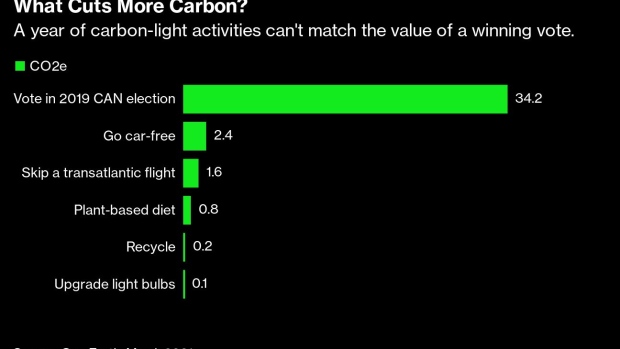

Wynes and his co-authors estimated the total emissions reductions those carbon-cutting policies might yield, refining that further with assumptions about the possibility of subsequent elections undoing them. When they distributed the final estimate of CO₂ cuts across all voters, the average reduction per voter was 6.7 tons CO₂e (carbon dioxide equivalent). When they assigned responsibility only to winning voters in winning districts, the carbon reduction for each vote was 34.2 tons.

Whichever assumptions they chose, the authors said, the emissions reduction linked to voting “is higher than most individual lifestyle decisions that the average person has the opportunity to make,” adding that if voting is comparable to lifestyle choices, “then we should regard the responsibility of voting as meriting the same level of moral consideration.”

The last section of the paper evaluated whether campaign contributions lead to more emissions reductions than buying valid, voluntary offsets. The authors looked at a losing 2018 Washington State ballot question that would have set up a state carbon tax. Using previous estimates of how much campaigns end up spending per vote, they found that political donations could have cut the state’s carbon output at a cost of about $7 a ton. That’s less than half of the price of the cheapest carbon offsets they reviewed and one-sixth what the US government has estimated the cost to be.

Some elections are too complicated to evaluate, including the 2020 US presidential election, because of the uncertainty surrounding a White House’s ability to move climate legislation through Congress, made clear in recent months by the fate of Build Back Better.What’s particularly interesting is that the paper, by making difficult estimates, sits right at the intersection of two central climate questions:

- What can an individual do to maximize their tiny role in a global problem?

- How can the individual compare actions that are easily measured, such as how much they drive, with actions that are difficult to quantify, such as participating in a democracy?

The amount of emissions per US voter in Wynes and colleagues’ exercise comes out to roughly twice per-capita emissions—or about 40 metric tons of CO₂e—because the emissions of children, minors and other non-voters are redistributed among registered US voters.

Deeper explorations of the question might take into account the effects of people’s behavior on other people. Frances Moore, an assistant professor at the University of California at Davis, in March led a study that incorporates people’s influence on each other into climate modeling—not something that you would think it took until 2022 to do—and found that behavioral feedbacks accelerated emissions reductions.

Despite necessary simplification, Wynes’s study is “nevertheless an interesting thought experiment that they are doing, just to look at the magnitudes and say, ‘Even if we take fairly conservative measures, these things stack up very favorably compared to other things that individuals can do,’” Moore said.

Experts and advocates warned away the question of individual responsibility for many years, with good reason. Excessive focus on individuals’ emissions distracts from the systemic nature of problem. That’s exactly why the fossil fuel industry, according to recent research, has spent hundreds of millions or billions of dollars in marketing to persuade people that consumption decisions matter more than energy company business models.

What’s new in Wynes’s framework is how it enables individuals to evaluate the most efficient way to spend a dollar reducing carbon.

Other research has put individual consumer and citizen actions front and center. The World Inequality Lab has shown that the richest 10% of the world—even more so the top 1%—are personally responsible for so much pollution that their decisions as consumers, employees, investors and citizens really do matter more than anybody else’s.

It’s still a massive systemic problem. And as Moore points out, voting more and driving an EV aren’t mutually exclusive.

“You could do both, right?” she said.

Eric Roston writes the Climate Report newsletter about the impact of global warming.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.