Apr 4, 2023

Bank of Canada rate hikes hitting immigrants and millennials hard

, Bloomberg News

Canada’s economy and society three years after the start of pandemic: Stats Can

Millennials and immigrants are bearing the brunt of the Bank of Canada’s aggressive interest-rate hikes. But baby boomers who own their homes outright aren’t likely to be feeling the pinch.

A generational wealth gap is at the root of the contrasting experiences of these cohorts. The central bank acknowledges the uneven impact of its rate moves and is studying how different segments of the population are faring as it pauses its hiking cycle.

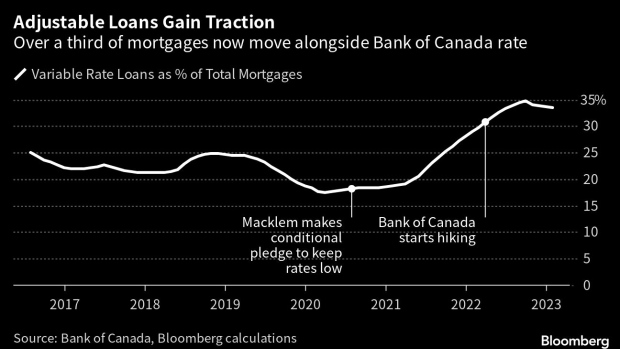

Younger generations and recent arrivals are more likely to be carrying heavy debt loads or have taken out large adjustable-rate mortgages to finance expensive homes during the COVID-19 real estate boom. Mohita Jajodia, 34, is among those now being squeezed, looking to cut expenses and delay major purchases.

Conversely, older generations remain mostly unscathed. Many have already paid off their mortgages — the biggest burden for Canadian households, which are the most indebted among the Group of Seven.

Governor Tiff Macklem is counting on a 425-basis-point jolt to interest rates, delivered in less than a year, to slow consumption and rein in soaring inflation. But differences in the impact of the hikes between the two camps are creating uncertainty around how and when the economy will cool.

Floating-rate mortgage holders and those in historically disadvantaged groups — Indigenous and racialized Canadians, as well as people with disabilities — are more likely to be hit harder by higher rates, a central bank survey released Monday showed. Less wealthy individuals also took a greater hit to their net worth as borrowing costs surged, according to the latest income distribution data from Statistics Canada.

Macklem’s own words before the hiking cycle began, meanwhile, also influenced the behavior of borrowers like Jajodia. She and her husband now see the vast majority of their adjustable-rate mortgage payments going toward interest, lengthening the amortization period for their Toronto-suburb home.

They moved to Canada’s financial capital from Mumbai in September 2020, when house prices started rising rapidly as emergency low interest rates spurred demand amid limited supply. Fearing missing out after - seeing their immigrant friends getting into the housing market during that run-up, they bought their first home in February 2022, spending nearly $1 million on a place an hour away from downtown.

A month later, Macklem and his officials started hiking interest rates, immediately sending house prices into a correction. Now, real estate values in the Halton Hills area that includes their Georgetown townhouse are down 23 per cent from a peak when they bought.

“All of this rush was because we wanted to be able to secure a lower rate. We weren’t anticipating the interest rates to increase by more than 400 basis points. We hadn’t built that into our calculations,” Jajodia said in an interview, adding that Macklem’s 2020 speech assuring that rates would be “low for a long time” influenced their thinking.

“I definitely regret the decision. There’s really nothing we can do. We’re just waiting for the rates to drop.”

In a stark contrast to Jajodia’s situation, retired Vancouverites Daniel Limawan, 62, and his husband have almost paid off their mortgage and aren’t affected by rate hikes. They’re now spending winter months living part-time in Lisbon after traveling through Asia earlier this year.

Next month, they will own their home outright, joining about 28 per cent of Canadian homeowners and 50 per cent of those in Vancouver who are mortgage-free. The couple, who used to work in the television industry, bought their hilltop house with a downtown view in 1999 for $315,000. Since then, its value is estimated to have jumped 470 per cent to $1.8 million.

“We feel sorry for people who just entered the housing market, especially in Vancouver and Toronto. How dreadful and dramatic it can be if you have to pay significantly more and it’s really out of your control,” Limawan said.

Economists estimate that with Macklem’s last hike in January, which brought the benchmark rate to 4.5 per cent, close to two thirds of variable-rate will have been triggered, meaning more of borrowers’ monthly payments will be shifted to interest from principal.

There’s also a swath of fixed mortgages about to renew at much higher levels. Unlike in the U.S., where households often enjoy the security of fixed terms in popular 30-year loans, many Canadians have to renegotiate their rates every five years.

Higher rates are hurting the nearly 40 per cent Canadians who rent their homes too. The steep deterioration in affordability, which presents a major barrier to home ownership for young adults, is driving up rental costs for families who are competing for scarcer housing as hundreds of thousands of immigrants enter Canada each year.

The Bank of Canada is acutely aware of the problem. In 2020, it setup what it calls the Heterogeneity Laboratory to “better understand the range of household experiences in the Canadian economy.” And officials from Macklem on down regularly concede that their rate hikes are hurtful but necessary.

“We know that the monetary policy tightening we’ve undertaken is hard on many Canadians,” the governor said in a Feb. 7 speech in Quebec City. “Unfortunately, there is no easy way to restore price stability. Monetary policy doesn’t work as quickly or painlessly as everyone would like, but it works.”