Apr 5, 2023

BOJ’s Kuroda Leaves $11.7 Trillion ‘Shock and Awe’ Experiment to His Successor

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Within weeks of taking office a decade ago, Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda fired his “shock and awe” stimulus targeting a return to steady 2% inflation in around two years. As his tenure ends, the original “time horizon” remains largely that — something within sight but out of reach.

Through 10 years of experimental policy that rewrote the rules of global central banking, Kuroda’s BOJ forked out 1.55 quadrillion yen ($11.7 trillion) on bonds, stock funds and corporate debt.

Deflation was tamed though not vanquished; businesses were kept afloat and zombie companies plodded on; workers kept their jobs even as productivity flat lined; the government funded vast spending programs and the deficit deepened; and the economy eked out modest expansions, though only Italy grew slower among major economies.

The staggering cost has economists asking: “Was it all worth it?” The answer may well depend on how his successor, Kazuo Ueda, handles his inheritance. Starting Sunday, he faces the daunting task of finding an exit path out of the unprecedented stimulus program without derailing the economic progress Kuroda made or battering asset values the world over.

In a reflection of Kuroda’s mixed legacy, a Bloomberg News survey of economists that bluntly asked whether he had succeeded or failed came down narrowly in his favor, 56% to 44%.

The loftiest praise stems from abroad, where many of the world’s largest central banks borrowed from the BOJ’s playbook.

“Kuroda will be recognized as having been an outstanding central bank governor who has been quite innovative,” former International Monetary Fund chief economist Kenneth Rogoff said. “The BOJ under Kuroda has forcefully adopted more or less every idea there is for raising inflation expectations, but until recently, to no avail.”

At Kuroda’s last Group of 20 meeting in Bengaluru, India, in late February, central bankers and finance ministers from across the globe rose to their feet to applaud the ever-smiling governor. European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde was one of the first to clap, according to people familiar with the matter.

“Haruhiko Kuroda is a master of his trade. He steered the monetary policy of Japan through challenging times. These are big shoes to fill for any successor – and times are certainly not getting any easier,” said Swiss National Bank President Thomas Jordan. “It was always a pleasure to have in-depth discussions with him over dinner, ranging from culture to economics to politics.”

Even as investors and economists became increasingly doubtful over the sustainability of the BOJ’s easing program, they marveled at his ability to fend off doubters — whether that meant spending trillions of yen buying bonds to beat off speculators or sticking to a tight script in endless hours of questioning by politicians in parliament, where he was frequently summoned.

“He kept the ship going quite well in Japan for 10 years, and that’s quite an achievement,” said Agustin Carstens, general manager of the Bank for International Settlements.

Policy Limits

But Kuroda has also demonstrated the limitations of unconventional monetary policy. His tenure shows that concentrated asset buying, known as quantitative easing, stabilizes markets in times of crisis but can’t conjure up inflation, higher wages and stoke growth without other supportive conditions.

Likewise, the BOJ’s strategy of holding down long-term bond yields proved to be no economic panacea.

“He has been very courageous in the different means and tools that he’s used to try and get from falling prices to something back above normal prices,” said Reserve Bank of New Zealand Governor Adrian Orr.

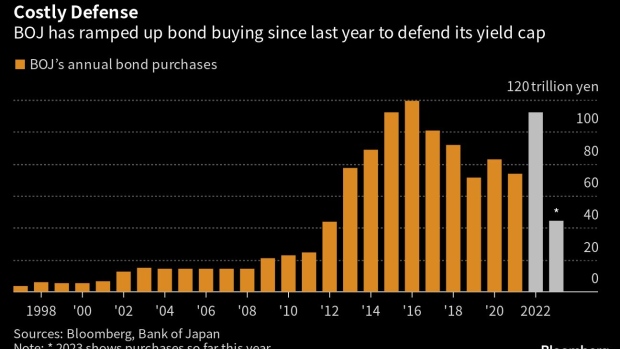

But it’s the massive cost of those tools that fuels the Kuroda critics. The BOJ under Kuroda spent 964 trillion yen on bonds, 541 trillion yen on short-term notes, 36 trillion yen on ETFs and around 7 trillion yen on corporate bonds, commercial paper and real estate investment trusts.

Much of the spending was to cover maturing debt as the BOJ had to dish out increasing amounts just to tread water. Netting that out, the tally of additional stimulus Kuroda added equates to about 500 trillion yen — or enough to pay every Japanese man, woman and child a check for roughly 4 million yen ($30,000).

Yet for most of his tenure, inflation remained nowhere close to Kuroda’s 2% goal, and when it did pick up it was largely sparked overseas by a post-pandemic recovery, supply-chain snarls and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The BOJ’s most recent price forecasts show that officials still don’t see inflation staying above 2% in a sustainable manner over the coming years.

“Kuroda’s achievement is demonstrating that monetary policy alone can’t get you 2% inflation,” said Shigeto Nagai, Japan head of Oxford Economics and former head of the BOJ’s international department. “Among the disappointments is that he impaired the functioning of financial markets. They are a key channel for monetary policy to have an impact.”

Liquidity was squeezed out of the bond market, first by the barrage of buying by the BOJ, then by the 2016 imposition of a yield target that largely batted aside market price functioning for 10-year government debt.

Kuroda’s yield curve control had its suitors overseas for a while. Both the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank took a look at it but decided against using it. The Reserve Bank of Australia did adopt a version of it, only to see it crash and burn in a wave of speculative pressure.

Bond vigilantes emboldened by the toppling of the RBA’s framework in late 2021 then set upon the BOJ’s settings. That prompted a renewed buildup of purchases to defend its yield targets that further drained the pool of bonds, causing successive days of no trading at all and more tweaks by the central bank.

Throughout his stint, Kuroda’s affable character and talkative nature helped pull people round while putting a soft cover over a steely streak of determination. His critics would call it stubbornness and say his increasingly convoluted explanations lost the simplicity of his original bold messaging.

Ueda has so far expressed none of the urgency to shift policy that Kuroda launched his tenure with. Ueda, the MIT-trained academic dubbed Japan’s Ben Bernanke by former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, has said that the central bank needs to continue easing for now.

But an eventual tightening of policy is widely expected. Most polled economists see some form of change coming by June, with the dismantling of the BOJ’s control of yields among the possible options while bond buying continues.

The tricky part is how to back away from towering stimulus without toppling markets. Japanese investors have $3.4 trillion overseas that may start flowing back to their home country if interest rates go up, with Australian and Dutch markets among the most exposed.

READ MORE: A $3 Trillion Threat to Global Financial Markets Looms in Japan

Economics 101 would suggest that a normalization of policy would also mean drawing down the central bank’s assets to create scope for taking action again in the future. That’s something the BOJ wouldn’t be able to do in any kind of hurry without causing huge waves in markets.

The BOJ’s bond holdings are larger than Japan’s GDP, far outstripping the scale of US and European interventions when measured against the size of their economies. Its stock purchases that have seen it become essentially the largest holder of firms including Advantest Corp. and TDK Corp. could take up to a century to divest at a pace that doesn’t cause ripples according to some estimates.

The thorniest part of Kuroda’s legacy is likely the government addiction to cheap lending his policies have helped develop.

Japan’s public debt load is 264% the value of its gross domestic product, the highest in the developed world. Since Kuroda took the helm, the country’s outstanding debt has increased by 40%, yet the annual debt servicing costs have only grown by 9% thanks to his ultra-low rates.

Just last month, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s government secured passage of another record annual budget. That suggests that while Ueda may be expected to slow Kuroda’s stimulus spigot over his term, he’ll be encouraged to do so slowly.

“Loosened fiscal discipline will be a challenge when the BOJ starts considering an exit,” said former BOJ Board Member Takahide Kiuchi, a staunch dissenter on the policy board from Kuroda’s very first meeting. “Ueda’s biggest responsibility will be to avoid triggering disaster for the finances of the country.”

In many senses, the success with which Ueda handles that and other challenges will determine how history ultimately views Kuroda’s term.

If the budding signs of inflation in sight now blossom into a sustainable 2% rate and Ueda manages an orderly exit from the current emergency policy settings, then Kuroda’s term will be deemed a success. If inflation peters out yet again or becomes too hot to handle and Ueda fails to keep markets sanguine, then Kuroda’s reputation will sink along with Ueda’s.

“If Ueda messes up, criticism is likely to also hit Kuroda,” said Naomi Muguruma, chief fixed-income strategist at Mitsubishi UFJ Morgan Stanley Securities. “Monetary policy isn’t a sport with a clear ending. I don’t know what inning we’re in, but it would be great if Ueda can hit a home run.”

--With assistance from Bastian Benrath, Michelle Jamrisko, Emily Cadman and Yuko Takeo.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.