Aug 15, 2019

Bond rally charges on with 30-year Treasury yields below 2%

, Bloomberg News

Explaining the recession signal that's shaking markets

Alarm bells are ringing louder in bond markets.

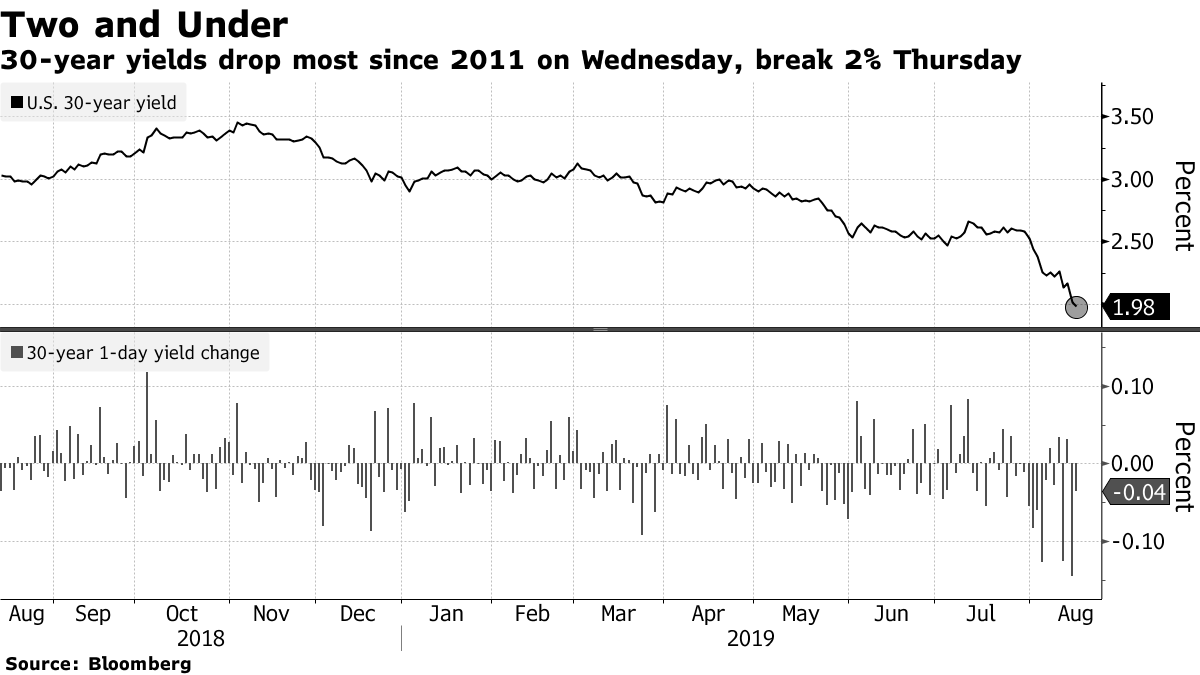

Among the superlatives: the yield on 30-year Treasuries fell below 2 per cent for the first time and the world’s pile of negative-yielding debt surpassed US$16 trillion. And looming over it all was the 10-year Treasury yield dipping below the two-year, in what’s considered a harbinger of a U.S. economic recession in the next 18 months.

That expectation, nurtured in recent weeks by worsening U.S.-China trade relations and signs global growth is slowing, was bolstered by weak Chinese and German economic data. The so-called yield inversion drew the ire of U.S. President Donald Trump, who tweeted that Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell is “clueless.”

“We’re heading into a global recession and central banks don’t have much ammunition to counter it,” said Nader Naeimi, AMP Capital Investors Ltd.’s head of dynamic markets in Sydney. “The huge shock from the trade war has basically offset whatever central banks are doing, and that’s some of the signals from the yield-curve inversion.”

The 30-year Treasury yield fell as much as six basis points to 1.9623 per cent in Asia trading on Thursday, after sliding 15 basis points the day before.

Meanwhile, an inversion of the 2-10 year yield curve that briefly occurred during New York trading surfaced again. The 10-year Treasury yield was as much as 1.3 basis points below the two-year rate on Thursday.

Bad European and Chinese data were the trigger for the global bond rally, said Praveen Korapaty, chief global rates strategist at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. “From the pace of the move, I suspect some long-held steepeners are being unwound as well.”

Another widely-watched recession indicator, the yield difference between three-month and 10-year Treasuries, inverted in March and has been negative much of the time since, bedeviling investors who anticipated that the curve would steepen as the Fed began to cut interest rates. The global rush for bonds also inverted the two-year to 10-year U.K. yield curve Wednesday.

Trump placed the blame for the “crazy inverted yield curve” squarely on the U.S. central bank, which he believes raised interest rates too quickly. The Fed’s reluctance to ease policy more aggressively is “holding us back,” he tweeted.

Yield curves normally slope upward as investors demand compensation for putting money at risk over longer periods.

As fears grow of a weaker economy in the future, investors drive down yields on longer-dated assets on expectation that rates will drop. There’s another incentive to buy longer bonds, and that’s due to the positive convexity value. This means that those with a longer duration will see larger price climbs in a rally than those with shorter maturities.

The U.S. bond market has been a destination for haven flows given that there are fewer and fewer positive-yielding assets to park cash in globally, according to Richard Kelly, head of global strategy at Toronto-Dominion Bank.

“The curve inversion to this point is flagging a 55-to-60 per cent chance of a U.S. recession over the next 12 months,” Kelly said. “We can all debate whether those signals are as accurate as they once were, but we still seem to be in a slow grind lower for sentiment and momentum and need some positive surprises to change those trends.”

The curve isn’t the only thing flashing high alert. The New York’s Fed index showing the probability of a recession over the next 12 months is close to its highest level since the global financial crisis, at around 31 per cent.

Others aren’t ready to sound the alarm yet. The Reserve Bank of Australia’s No. 2 official weighed in on the debate on Thursday questioning the value of using the inversion as a sign of recession.

“At the moment the U.S. economy is actually growing above trend so they’ve got a fair way to slow from here,” said RBA Deputy Governor Guy Debelle. Trade disputes are a key risk, though, he said.

There’s little evidence in U.S. economic data to suggest a recession is imminent, according to Goldman’s Korapaty, who sees the 10-year yield returning to 1.75 per cent by year-end.

Others including macro hedge fund Ensemble Capital are more wary of rising recession risks.

“Yes, recession is coming,” according to Ensemble’s Chief Investment Officer Damien Loh. “The ball’s in the court of the White House and Trump given the flip flops on trades we’ve seen.”

--With assistance from Emily Barrett, Greg Ritchie and Michael P. Regan