May 24, 2022

Central Banks Fret as Inflation-Linked Pay Bumps Stage Comeback

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

It’s not just a fear of 1970s-style inflation that has central bankers on edge -- but also a return of measures enacted to keep workers happy all those years ago.

Cost-of-living mechanisms that bind salary gains to increases in consumer prices risk staging a comeback, the Bank for International Settlements noted recently, warning they could contribute to a possible wage-price spiral.

So-called indexation, while still popular in places like Belgium and Cyprus, had fallen out of favor as inflation moderated. But it remains a bugbear of policy makers for its capacity to prolong and amplify bouts of upward pressure on prices, with interest rates already being lifted aggressively around the world.

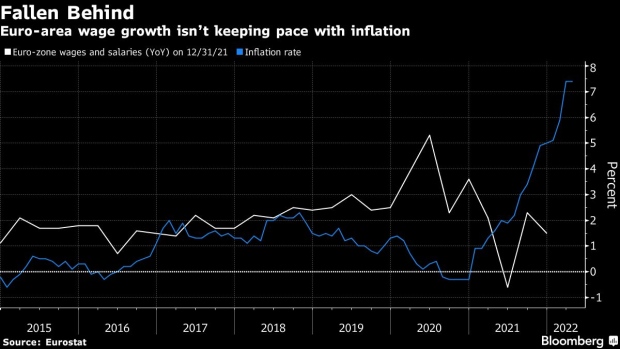

Highlighting frustration at waning purchasing power, a staff union at the European Central Bank sought pay rises in line with euro-zone inflation -- currently a record 7.4%, more than three times the official target.

While President Christine Lagarde rebuffed that request, the ECB isn’t alone in being asked. Almost a third of registered labor agreements in Spain in the first two months of 2022 included indexation clauses. In the US, workers at Kellogg Co. ended a pay dispute late last year after securing cost-of-living boosts.

For Ricardo Reis, a professor at the London School of Economics, the renewed verve for inflation-linked pay signals dwindling faith in policy makers’ ability to control prices.

Central banks “should be very worried that people are trusting the inflation target so little that they’re choosing to insure against inflation with indexation,” he said. This makes their task “much harder.”

While there are a handful of cases in the US -- union members at tractor maker Deere & Co. achieved a similar deal to the Kellogg workers -- the greater power of European labor groups means there’s more concern there about demands for inflation-linked wage boosts.

Spanish central-bank data show the share of such arrangements swelling from less than a fifth. The ECB has found that, until recently, Spain played a key role in lowering the euro zone’s proportion of inflation-adjustment mechanisms among private-sector workers -- from almost a quarter in 2008 to 16% in 2021.

The issue is clearly on policy makers’ minds: ECB officials meeting in October discussed how 1970s stagflation occurred in an environment in which “indexation allowed wages to react to energy prices and thus sustained both stagnation and inflation.”

Vice President Luis de Guindos has said such second-round effects are being monitored.

‘Show Restraint’

Even without outright indexation, other remedies to soaring inflation can complicate efforts to tame prices. Germany’s steelmakers’ union wants a 8.2% pay bump. Germany and France are either raising minimum wages or facing calls to do so.

But central banks should expect little sympathy. Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey sparked an uproar in February by urging workers to “show restraint” in salary demands as inflation squeezes consumer spending by the most since World War II.

“The absence of indexation means workers are always the ones to take a hit when there’s a price shock,” said Carlos Bowles, an ECB economist and the vice president of the IPSO staff union whose requests were rejected by Lagarde.

Bowles says indexation has helped restore social harmony in the past, and that unions’ bargaining power today is often insufficient to recoup losses caused by inflation.

For now, there’s little evidence that the dreaded wage-price spiral is emerging. But the BIS warns that “inflation may yet create the conditions for it to become entrenched,” pointing to anecdotal calls to make up for lost purchasing power.

There are “certainly circumstances” under which salary gains are appropriate and a sign of healthy economies, according to Tina Zumer, a deputy governor at Slovenia’s central bank who keeps tabs on euro-area wage developments.

“The risk in this situation is that they could be rising at a time when growth is weakening,” she said. “That would force companies to pass on higher labor costs to consumers, reinforcing the inflation problem.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.