Mar 20, 2023

China-Russia Gas Talks to Show How Much Xi Is Embracing Putin

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- China has billed Xi Jinping’s trip to Moscow this week as a “journey of friendship.” Talks on a long-term gas deal may reveal the limits of what he can and will do for Vladimir Putin.

Russia, which was the world’s largest gas exporter until it invaded Ukraine last year and lost access to most of its key markets in Europe, is eager to boost shipments to China. But that requires new pipelines, since much of Moscow’s existing export infrastructure faces West.

Even as Russia has ramped up gas deliveries to China since the invasion through an existing pipeline under a pre-war deal, supplies via another link haven’t started. And talks on third route that would carry more gas than the first two combined so far haven’t yielded a contract. Those discussions remain a bellwether of just how far China is willing to depend on Russia for key energy supplies.

“There’s definitely potential for further deepening of energy cooperation between countries, but if China becomes over-reliant on Russian energy imports, does that create risks in the future?” said Kevin Tu, the managing director of Agora Energy Transition China. “That’s a factor that China needs to consider.”

The Kremlin said Friday that talks would include detailed discussions on energy, but conceded that China’s sending mostly government officials and Russian energy executives will appear at the concluding state dinner. There was no indication of whether a deal on the third gas pipeline, known as Power of Siberia 2, would be on the agenda.

Energy supplies are a key source of cash for Putin to sustain his war in Ukraine as the US and its allies continue to supply the government in Kyiv with weapons to fight back. While China has avoided directly providing Russia with lethal support, it remains Putin’s most important diplomatic and economic partner, and a key source of revenue.

“I see a reaffirming of the relationship, a show of political support — what is less clear is how that translates into something tangible,” said Ja Ian Chong, an associate professor of political science at the National University of Singapore.

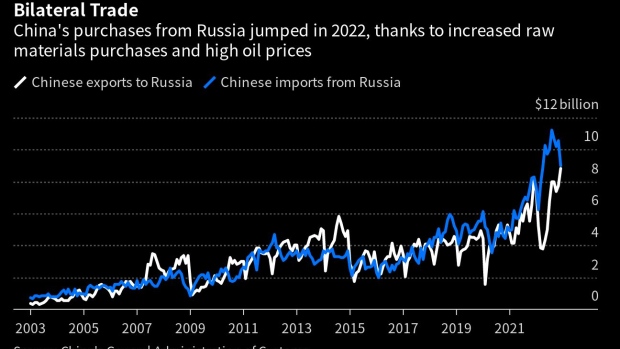

Since the invasion of Ukraine, the world’s largest oil importer has already been a crucial source of support for Russia, cut off from Western markets and grappling with an unprecedented array of sanctions. Partly thanks to high oil and gas prices, bilateral trade hit a record in 2022.

China’s import data show Russia is its second-biggest supplier of crude oil and coal, after Saudi Arabia and Indonesia, respectively, and No. 4 for liquefied natural gas. (The last ranking doesn’t include the volumes of gas piped overland, which China stopped reporting at the beginning of last year.) In the last 10 months of 2022, China’s purchases of Russian energy — crude oil and products, natural gas and coal — ballooned to $74.3 billion, from $46.8 billion in the corresponding period of 2021.

China hasn’t recognized a price cap on Russian crude imposed since December by the Group of Seven industrialized countries and their allies, and doesn’t appear to be buying below the $60-a-barrel level — though opaque pricing makes that difficult to establish with certainty.

According to the International Energy Agency, China, together with India, took in more than 70% of Russia’s crude exports last month.

Coal sales have picked up, and the first railway bridge across the Amur River will help, easing transport bottlenecks over the inland Trans-Siberia network. China’s significance is also growing in metals, which remain unsanctioned.

MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC, a top source of nickel, has been in talks with its Chinese clients to ink long-term contracts based on Shanghai prices. Rusal, the world’s biggest aluminum producer outside China, boosted sales to Asia last year, but also increasingly relies on China as a source of alumina, after Australia banned its export to Russia and its Ukrainian plant in Mykolayiv was idled by the war and seized by Ukraine this year.

Yet gas may well be the biggest question mark during Xi’s visit. Last month, at the 30th anniversary of Gazprom PJSC, Putin said that the Asia-Pacific — and China in particular — will drive global demand for gas over the next 20 years, making it essential to develop gas production, processing and shipment facilities in Russia’s East.

Gas flows last year via the Power of Siberia link, which was launched at the end of 2019, rose almost 50% to 15.5 billion cubic meters — and they’re set to reach 38 billion cubic meters a year by 2025. In September, Gazprom signed an additional agreement to its $400-billion contract with China National Petroleum Corp. - the biggest in the history of Russian gas producer — to shift payments to rubles and yuan from euros.

The second Far Eastern pipeline is set to eventually deliver a further 10 billion cubic meters of gas a year. The Power of Siberia 2 project, which is now under discussion, would then potentially ship as much as 50 billion cubic meters a year. Critically, it would supply gas from the Yamal Peninsula, the same region from which Russia sources European exports.

“The Chinese seem to be under no time pressure to negotiate,” Vitaly Yermakov, senior research fellow at The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, said earlier this year. “While Russia is sitting on a time bomb, facing a potential sharp reduction in gas export volumes, and wary of the fact that the counterbalancing effect on export revenues from today’s very high gas prices is likely to start dissipating in the next few years.”

--With assistance from Kathy Chen, Alfred Cang, Serene Cheong and Dan Murtaugh.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.