Jul 21, 2022

Despite Abe’s Push, Women Still Largely Absent From Japan Boards

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe left behind a mixed legacy for working women in Japan, with strong labor force gains masking persistent shortcomings in the country’s boardrooms.

Among the things Abe, who was fatally shot at a political event this month, will be most remembered for was his audacious growth plan for Japan as the population shrinks and economy stagnates. A core part of that was dubbed “womenomics,” a government initiative that sought to encourage more women to join the workforce.

Womenomics policies required large Japanese companies to produce action plans for hiring and promoting more women and pressured companies to pay female employees the same as men. Under the womenomics rubric, the Abe government also worked to expand access to childcare options.

The policies saw some success. During Abe’s eight years in office, millions of women joined Japan’s workforce. The country’s working-age female labor force participation rate was 73% in Abe’s last full year as prime minister in 2019, according to the World Bank, up from 64% in 2012 when he began his final term.

“What Abe did was elevate women’s economic empowerment to be a collective initiative for Japan,” said Jackie Steele, a political scientist and founder of enjoi Japan K.K., a consultancy that seeks to promote diversity and equity in Japan. “Abe helped to create coordinated discussion around gender equality as a pillar of the macro economy and Japan’s competitiveness on a global scale.”

Slow Drip

To be sure, many of the new female workers joining Japan’s workforce were filling so-called irregular positions, a term that encompasses employment that’s part-time, temporary, or under contract. Those jobs were more vulnerable to coronavirus-triggered slumps in economic activity, meaning women made up the bulk of jobs lost in the early months of the pandemic.

It was at the senior level, however, that Abe’s policies disappointed. Despite Abe’s proclaimed goal of having women fill 30% of leadership positions, the flow of women into boardrooms in Japan has remained a slow drip. Women filled 258 of 2,410 seats on Nikkei 225 Index-company boards when Abe stepped down in September 2020. That figure has changed little since, standing at 305 for the recently ended quarter, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

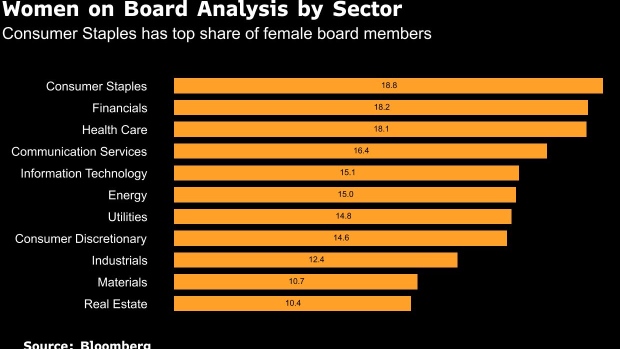

Japan’s 14% of women on boards compares with 32% for S&P 500 firms in the US and 17% for companies on the Hang Seng Index in Hong Kong.

With many female workers disproportionately occupying lower-paying and irregular jobs, “it’s questionable whether women today are actually able to shine,” said Kumiko Nemoto, a professor at Senshu University, alluding to Abe’s well-known pledge to make Japan a nation where women could do just that.

The country’s rank in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index is even worse than a decade ago. In the latest rankings released last week, Japan placed 116th out of 146 countries.

Read More: Goldman’s Womenomics Stocks Languish in Inflation-Wary Japan

Japan’s lack of progress boosting its number of female executives comes down to long-standing, age-based promotion practices, according to Nemoto. It’s custom for an employee to have to spend 15 to 20 years at a company before being promoted to the managerial level, which is problematic given that two decades ago companies were hiring only four or five women for every 200 men, she said.

“Japanese companies complain that they don’t have a pipeline of qualified women to serve on boards, but that’s because 20 years ago they weren’t hiring any,” Nemoto said. Japanese companies today are hiring more women and two decades from now that will likely contribute to the pipeline of female managers. For more immediate results, companies need to loosen rigid systems of internal, age-based promotion, she added.

Kishida’s Task

The question now is how Prime Minister Fumio Kishida will carry Abe’s equality initiatives forward. In the nine months since he took office, he has implemented several of his own measures including one that would force big firms to disclose gender wage gaps. So far his moves have been seen as largely lacking teeth.

One move that Kishida can make is to take existing womenomics policies and give them clearly outlined, meaningful compliance mechanisms, said Steele. That would help counter other systems built into Japanese society today -- such as taxation methods -- that are based on a male breadwinner-household model that privileges men for permanent positions while funneling women into irregular, non-career track jobs.

“Womenomics was the tip of the iceberg, but going forward what needs to be addressed is the part still under water -– the more structural inequalities within Japanese society,” Steele said.

Women held 32 more seats on the boards of companies in the Nikkei 225 Index in the second quarter from the previous three-month period, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The average number of female directors rose to 1.5 from 1.4, out of an average board size of 10.5.

- The percentage of female directorships increased to 14.4% from 12.9%

- That’s below the 35% of women on boards of the S&P/ASX 200 in Australia, 32% of the S&P 500 in the U.S., 39% of the Stoxx 600 in Europe and 17% in Hong Kong

- 31 Nikkei 225 companies increased the number of women on their boards; Central Japan Railway Co., Fuji Electric Co. and Toto Ltd. no longer have all-male boards

- Two companies reduced the number of female directors: Tokyo Gas Co. and Takashimaya Co.

- M3 Inc. has the highest percentage of women on its board

- The health-care sector led the net gain in female board members, with two women added to the board at Astellas Pharma Inc.

- Tokyo Electron Ltd., Japan Post Holdings Co. and Ajinomoto Co. are among companies that surpassed 30% female board membership for the first time since at least January 2019. The number of Nikkei 225 companies above this key threshold rose to 15 in June from nine the previous quarter

- 13 companies, including Shin-Etsu Chemical Co., Canon Inc. and Nexon Co., have no female board members

- The Bloomberg Gender Equality Index dropped 15% in the second quarter, outperforming the MSCI World Index, which fell 16%

Nikkei 225 companies with the highest and lowest percentage of female board members:

To see the percentage of women on a company board: FA ESGG

To see more on Bloomberg Gender-Equality Index: GEI

To see more on Bloomberg’s ESG fields and sustainable finance solutions: BESG

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.