Oct 7, 2020

Grocery Giant Tesco Sets Its Sights on Ocado

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Ken Murphy, the new chief executive officer of Tesco Plc, finds Britain’s biggest grocer in much better shape than his predecessor did when he took charge. It has prospered during the pandemic, helped by its big out-of-town stores and the ability to ramp up online capacity much quicker than its more fashionable internet competitor Ocado Group Plc.

Taking the helm of a company in relatively decent health brings its own challenges. When Dave Lewis became CEO six years ago, he faced the worst crisis in Tesco’s 101-year history after an accounting black hole created a 250 million-pound ($323 million) profit shortfall. But it was obvious what he needed to do: Right the ship, strengthen the balance sheet and fight the increasing threat of German discounters Aldi and Lidl.

Murphy doesn’t have such a clearly defined emergency mission. Tesco is chugging along nicely, forecasting on Wednesday that this year’s retail operating profit from continuing operations would probably be at least as good as last year’s. That’s despite the 725 million-pound additional cost to Tesco of managing the pandemic.

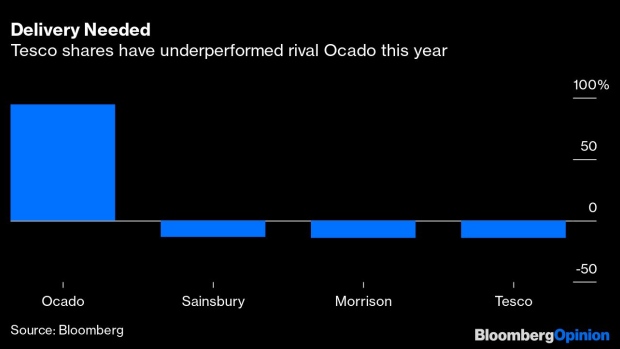

The new boss, a former senior executive at Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc., still has plenty of work to do — including narrowing Tesco’s stock market discount to Ocado, an online-only grocer that also licenses its technology to other giant supermarkets. This year Tesco shares have slightly underperformed brick-and-mortar rivals such as J Sainsbury Plc.

Murphy says new fulfilment centers in big stores for online deliveries will be a game changer for his company, helping it to chip away at Ocado’s position as web grocer of choice for Britain’s middle classes.

Elsewhere, there’s more value to be wrung out of the near 4 billion-pound purchase of wholesaler Booker in 2018. Tesco used Booker’s vehicle fleet to provide an extra 100,000 click-and-collect slots during the pandemic. Murphy will also need to make a call on whether to close or expand Tesco’s Jacks value chain.

And he could offload Tesco’s bank, which has never lived up to its promise. Murphy says there are no plans to sell the lender, but it’s an obvious source of cash if that were ever needed.

The chief criticism of Lewis is that he didn’t cut prices quickly enough to meet the threat of the German discount giants. Aldi’s lack of a serious online business means Tesco has used the pandemic to win customers from it for the first time in a decade. This advantage will not last forever, particularly if the British economy deteriorates. Aldi U.K. said recently that it wouldn’t be beaten on price.

Murphy appears to be acutely aware of the need to keep his foot on the price-cutting pedal. And he has the balance sheet firepower to do this. Net debt including store leases fell slightly to 12.5 billion pounds in the first half, while Tesco generated free cash flow of 554 million pounds from its retail operations.

Eking out incremental sales growth and slogging it out daily with the no-frills supermarkets is hardly the stuff of retail management dreams, especially when compared with Lewis’s rescue job. But if Murphy can fine-tune Tesco — and use its strong cash generation to return even more capital to shareholders — they’ll forgive the lack of fireworks.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andrea Felsted is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She previously worked at the Financial Times.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.