Oct 29, 2021

How sustainable debt is turning corporations into climate leaders

The rapid rise of sustainable debt

Imagine if you could get a lower mortgage rate every time you made some effort - perhaps by swapping out your incandescent light bulbs for LEDs or slapping some solar panels on your roof - to lower the carbon footprint of your home.

For the corporate world, the rapid rise of sustainability-linked debt products have made that their reality. Despite being around globally for less than a decade -- and less than two years in Canada -- loans, bonds and credit facilities with interest rates that are adjusted up or down each year depending on how much progress the company makes (or doesn’t) against pre-established sustainability targets are becoming so popular that experts expect they will soon become standard clauses in all corporate debt.

“We are at a critical juncture in corporate history where sustainability is becoming a megatrend that is forcing a fundamental shift in how companies compete with one another,” Carol Liao, a University of British Columbia law professor and a distinguished scholar at the school’s Dhillon Centre for Business Ethics, said in an interview. Linking sustainability targets to companies’ debt, she said, “is hitting them where they feel it the most.”

‘SHARP INCREASE’

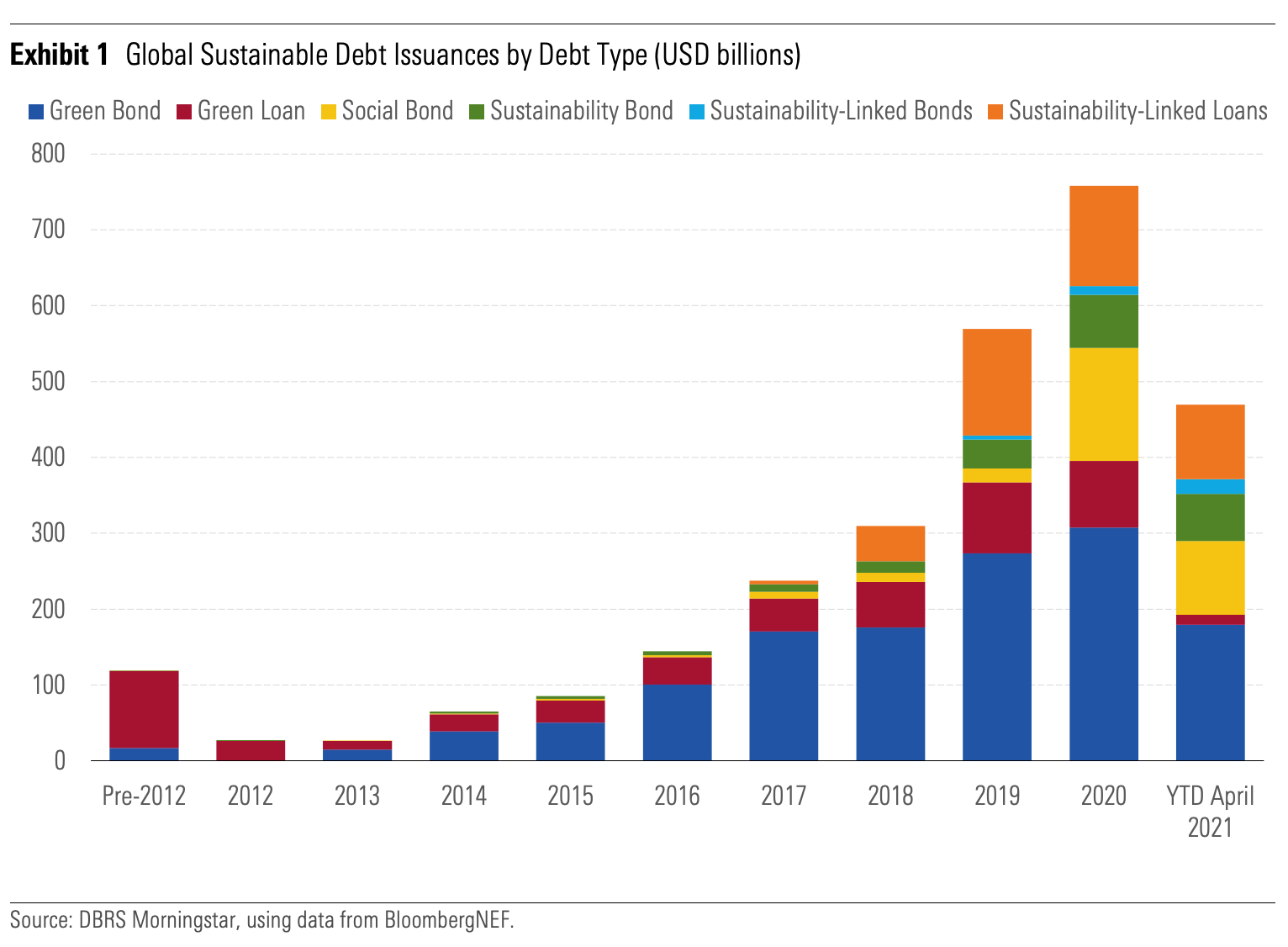

Global growth of sustainable debt issuances, including green bonds and loans, sustainability bonds and sustainability-linked bonds and loans, has grown from less than US$100 billion in 2015 to US$730 billion in 2020, according to a June report from DBRS Morningstar. The total for this year was approaching US$500 billion by the end of April, less than halfway through 2021, the report said.

While green bonds and other debt products where the proceeds must be spent specifically on environmental projects have been around in Canada for many years, the first sustainability-linked corporate loan wasn’t issued in this country until the end of 2019. That was when Maple Leaf Foods Inc. agreed to amend its existing credit facility with BMO Financial in order to reduce its interest rate if the company “meets targets on electricity use, water use, solid waste and continuing to reduce its carbon emissions.”

More than a dozen Canadian companies have followed, with Canada’s sustainable corporate debt market expected to hit $20 billion this year. Exact figures are not available, though Ryan Riordan, head of research at Queen’s University’s Institute for Sustainable Finance (ISF), estimates roughly one out of every six dollars of corporate debt issued in Canada over the past 12 months have had sustainability linkages included.

As of Oct. 26, National Bank’s total exposure to sustainability-linked loans was $2.5 billion, spokesperson Jean-Francois Cadieux said via email, noting the figure represented “a sharp increase” from roughly one year ago when the bank’s exposure to those debt products was only $274 million.

“In the beginning, what I observed was that a lot of these products were very small scale in a ‘let’s test the market and see how this works and let’s learn’ kind of way,” Riordan said. “And now you’re seeing much larger deals where instead of it being for under $100 million it is for $1 billion or more.”

Two major heavy industry players in Canada have added sustainability linkages to their debt in just the past two weeks. Teck Resources announced a US$4-billion revolving credit facility on Oct. 19 where the interest rate will increase or decrease based on the Vancouver-based mining companies performance in reducing carbon emissions, improving health and safety and strengthening gender diversity in its workforce.

Less than one week later, PrairieSky Royalty Ltd. announced it had nearly doubled an existing line of credit from $225 million to $425 million, while adding sustainability-linked criteria to its interest rate with its performance measured annually by Sustainalytics, a third-party research firm owned by Morningstar.

‘FANCY DANCY WORDS’

Using a broad term like “sustainability” is to some extent problematic, Riordan said, since it is a broad enough term that it could be used in bad faith.

“A sustainable business model, for example, has cash flows that are greater than costs,” he said. “We are sort of stuck in this equilibrium though, where we call it sustainability and the problem is that people throw things under there that maybe I don’t think fit under there.

However, the issue isn’t “black or white,” Riordan said, since “there is a lot of real activity in addition to a lot of potential for overhyping.”

Royal Bank of Canada spokesperson Andrew Block, who said in an interview that sustainability-linked loans are among the “fastest-growing” forms of corporate debt RBC issues, explained it in terms of applying “beyond just the environment, like the ‘S’ and the G’ in ESG,” he said, referring to “social” and “governance” issues.

“That is one of the common misunderstandings that people have about these products,” Block said.

Teck’s recently-announced sustainable debt, for example, includes targets for gender diversity and workplace safety along with its emissions reduction goals. In fact, there is some benefit to broadening the terms of sustainable debt beyond environmental metrics.

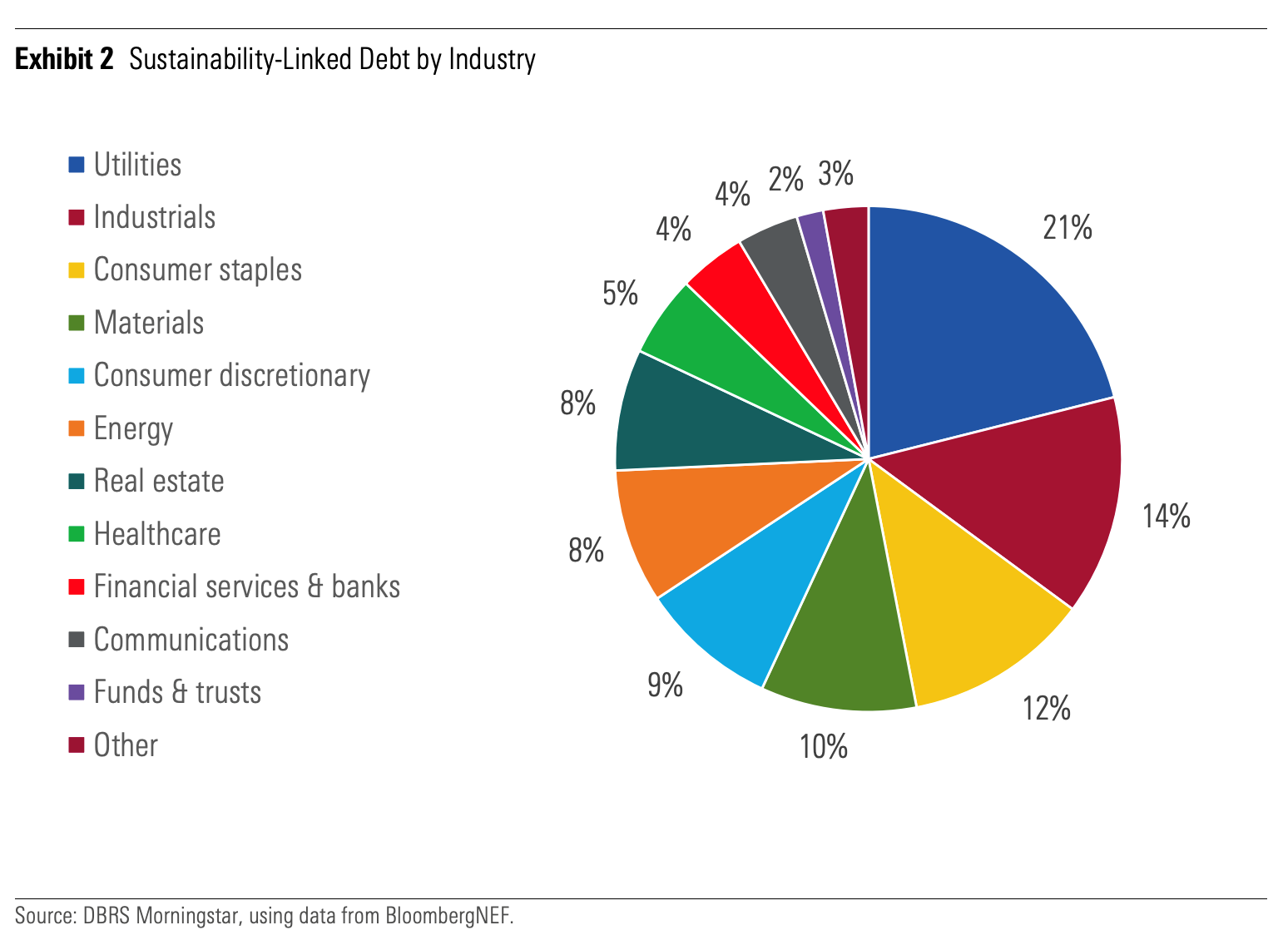

“Some companies in industries such as consumer staples and industrials may not be able to identify ESG-related projects in which to invest [and] as a result, they cannot issue [debt such as green bonds],” notes the DBRS report, “whereas sustainability-linked debt instruments are available to companies in all industries.”

While sustainable debt is still more common in emissions-heavy industries such as utilities, the report found industries such as health care and consumer discretionary make up sizable portions of demand for those products at 10 per cent and eight per cent respectively.

Most of the sustainability-linked debt products issued to date (88 per cent) do have incentive mechanisms tied to achieving environmental targets, the DBRS report found, versus 27 per cent having social-related key performance indicators (KPIs) and 11 per cent linked to corporate governance initiatives.

“We do see our clients that are not in heavy industries, that are in telecoms or banking or other industries, the desire to tell their sustainability story,” Jon Hackett, co-head of energy transition and head of sustainable finance at the Bank of Montreal, said in an interview. “They want to be able to demonstrate that they’re not resting on their laurels.”

Ultimately, “there is a shelf-life for all these fancy-dancy words,” said UBC’s Liao, noting the term “corporate social responsibility” or CSR “was huge at one point” but eventually lost popularity.

“The evolution of corporate law has allowed for the fragmentation of accountability, which is why it is really essential that existing products integrate the realities of sustainable practices in order to mitigate that fragmentation,” she said. “That is why I like these [sustainability-linked debt] products, because they meet that complexity, they form a piece of the sustainability jigsaw puzzle.”

‘THE SYSTEM DOES ITS JOB’

Offering better access to capital for companies making the most progress towards carbon neutrality “could be one of the most effective ways to incentivize good behaviour,” Liao said. “This could prove to be among the best ways to encourage businesses to transition into a new era of corporate governance that is appropriate to the level of risk we are facing under a global climate emergency.”

BMO’s Hackett agrees sustainable debt products represent “the right tool today and the right tool for companies to demonstrate that they are establishing programs and getting traction against what can be very difficult goals.”

“If we think about this in terms of incentivizing ambitious progress against those goals, it is very hard not to say that we need to meet people where they are,” he said, explaining why it would be counterproductive to try and establish standardized metrics on which companies' progress could be measured. Currently, the goals set in any given sustainable debt product are, to some extent, bespoke based on the unique circumstances of each company.

Attempting to enforce a one-size-fits-all set of sustainability standards would inevitably make them unattainable for some and too easily attainable for others, Hackett said.

For the ISF’s Riordan, the growing use of sustainable debt products is simply how capitalism is responding to climate change, whereby the companies that have the strongest sustainability goals “get allocated more capital, they do more of the abating and the system does its job.”

“I’m sure more can be done,” Riordan said, “but we also have to recognize what the financial system can do and I think this is what it can do, it can allocate capital.”

Beyond simply offering better interest rates to corporations making the most climate progress, there are other elements of sustainable debt products that are adding to their popularity.

“If you’re going to the debt market anyways, this is a better way to do it,” said RBC’s Block, noting it has become easier for corporations to access sustainable debt products than more traditional debt. “There is just a higher demand for those types of products from investors where investors and other stakeholders are just generally looking more for companies that utilize those products.”

Because of what he described as “massive” demand, Riordan said sustainable debt products have also become the most efficient and cost effective way to get access to capital.

“You can just imagine, say you need to raise a billion dollars. You might break it into four $250-million traches in order to give the market time to digest what you’re doing, but then when you see what the demand is like in the sustainable debt market you realize, ‘hey, I don’t have to do this four times and I won’t have to give up any concessions by doing this all at once by pushing investors too far,” he said.

“This is not niche lending anymore, this is large money market bond funds who will buy this stuff at a premium and stick it into their fund and sit on it, or insurance companies and major pension funds,” Riordan said. “Sustainable debt is no longer part of the one-per-cent-niche part of a portfolio. It is part of core holdings.”

‘PART OF NEARLY EVERY CONVERSATION’

The idea, he said, is that “at some point we won’t even have to put these clauses into lending agreements at all just because they will be pervasive” and UBC’s Liao argues that is already in the process of happening.

“Everyone can see the writing on the wall,” she said. “They need access to capital, every business does, and this is increasingly the best way to gain that access.”

BMO’s Hackett also said sustainable debt products “are becoming pervasive.”

“Sustainability linkages are part of nearly every conversation we have with clients around refinancing or net new debt,” Hackett said. “It is very rare that we would not integrate a conversation around sustainability linkages while talking about debt with our clients.”

The cyclical nature of the debt market is the only real limitation left, he explained, since the process of refinancing, renewing or accessing new corporate debt only occurs at certain times. Announcements of sustainable loans or bonds made today started with conversations that began a year or more earlier, Hackett said, but corporations across all industries appear to be moving towards the same destination where the interest on virtually all their debt is tied to their progress on sustainability.

“That journey has accelerated rapidly as corporations adopt sustainability targets and integrate them into a senior-level view of the organization,” Hackett said. “At this pace, I wouldn’t be surprised if we get all the way there within the next two to three years.”