Oct 11, 2022

IMF warns 'worst is yet to come' as steps to slow inflation raise risks

, Bloomberg News

There is an economic storm brewing, 2023 will be a rough year for markets: David Rosenberg

The International Monetary Fund warned of a worsening outlook for the global economy, highlighting that efforts to manage the hottest inflation in decades may add to the damage from the war in Ukraine and China’s slowdown.

The IMF cut its forecast for global growth next year to 2.7 per cent, from 2.9 per cent seen in July and 3.8 per cent in January, adding that it sees a 25 per cent probability that growth will slow to less than 2 per cent.

The risk of policy miscalculation has risen sharply as growth remains fragile and markets show signs of stress, the IMF said Tuesday in its World Economic Outlook. About one third of the global economy risks contracting next year, it said, with the U.S., European Union and China all continuing to stall.

The impact of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy tightening will be felt globally, with the dollar’s strength versus currencies in emerging and developing markets adding to inflation and debt pressures.

Excluding the unprecedented slowdown of 2020 because of the coronavirus pandemic, next year’s performance would be the weakest since 2009, in the wake of the global financial crisis.

“The worst is yet to come, and for many people 2023 will feel like a recession,” the lender’s chief economist, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, wrote in a foreword to the report. “As storm clouds gather, policymakers need to keep a steady hand.”

The warning comes as finance and central bank chiefs gather in Washington for the lender’s annual meetings. Speaking at the opening on Monday, IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva cautioned that higher borrowing costs in the U.S., the world’s largest economy, are “starting to bite,” while World Bank President David Malpass flagged the “real danger” of a global recession.

To be sure, the IMF sees greater risk from central banks doing too little rather than too much amid persistent price pressures, a mistake that would cost them credibility and only increase the eventual cost to bring prices under control.

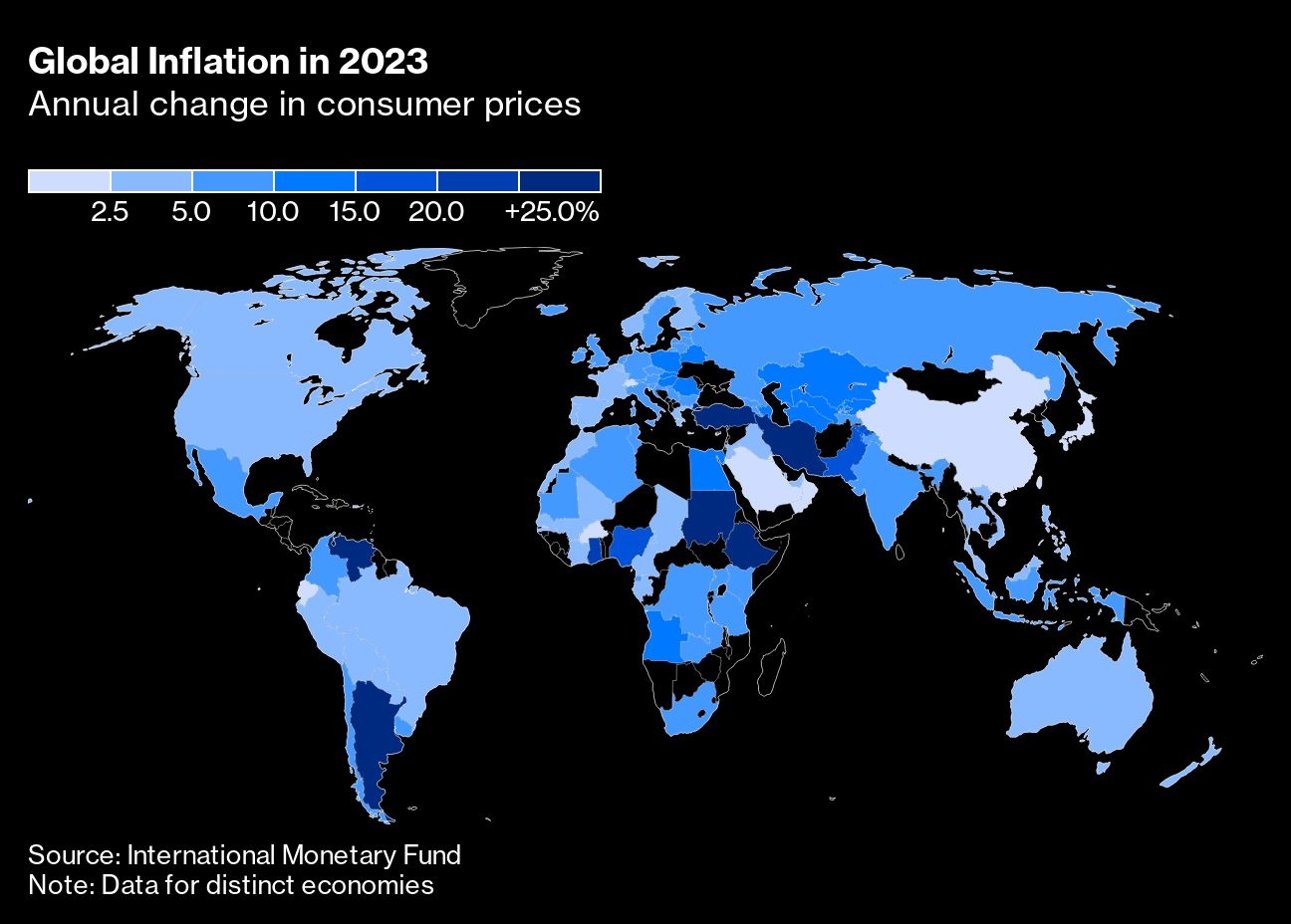

Inflation will peak later this year, the IMF forecast, with an annual rate of 8.8 per cent, and will remain elevated for longer than previously expected, only slowing to 6.5 per cent next year and 4.1 per cent by 2024.

For this year, the IMF sees world growth of 3.2 per cent, unchanged from July but down by more than a quarter from the 4.4 per cent projected in January, before Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered an invasion of Ukraine, which disrupted food and fuel flows and exacerbated inflation globally.

The euro area economy will grow just 0.5 per cent in 2023, according to the fund, with the bloc seeing the sharpest outlook reduction among global regions. Germany, Italy and Russia all will see their economies shrink.

Though the energy crisis in Europe triggered by Russia cutting deliveries of natural gas will challenge the continent this winter, next winter is likely to be even more difficult, according to the fund.

As countries deal with the energy crisis that’s elevating prices, Gourinchas urged nations not to implement fiscal policy that is going to be at cross purpose with what the central banks are trying to do.

“If you try to do this, it’s like trying to drive a car with two drivers,” he said in an interview on Bloomberg Television. “It’s not going to work,” he said, adding: “You want to make sure that you don’t create nervousness in the market and that you have a fiscal plan that doesn’t aggravate the inflation pressures.”

The U.S. will expand 1 per cent next year, unchanged from the previous view. It saw its outlook for this year cut the most, to 1.6 per cent growth from 2.3 per cent seen in July.

India will expand the most among the world’s biggest economies next year, growing 6.1 per cent. China will grow 4.4 per cent.

The recession in Russia won’t be as steep as expected in July, with the nation now seen contracting 3.4 per cent this year, compared with an earlier forecast for 6 per cent. Brazil also saw its forecast for this year increased by 1.1 percentage point to 2.8 per cent.

There’s a risk that a stormy global economy spur investors to safe-haven assets like U.S. Treasuries, pushing the dollar even higher and pressuring the debt of emerging and developing nations.

“Now is the time for emerging market policymakers to batten down the hatches,” Gourinchas wrote. That includes eligible countries requesting access to precautionary support from the IMF.

The world needs progress toward orderly debt restructurings through the Common Framework created by the Group of 20 largest economies for the most affected low-income nations, Gourinchas wrote.

“Time may soon be running out,” he said.