Oct 13, 2023

Industries Bruised by Energy Crisis Are Moving Into LNG Trading

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Industries from chemicals to utilities that rely on natural gas have a solution to the threat of high costs and supply shocks: Buying liquefied natural gas directly.

Companies are starting to source the super-chilled gas straight from producers at a lower cost by cutting out traditional suppliers who pass on the fuel. Buying LNG directly or setting up trading businesses would be more economical for as many as 45 firms around the world in sectors that also include manufacturing and mining, according to consultant Accenture Plc.

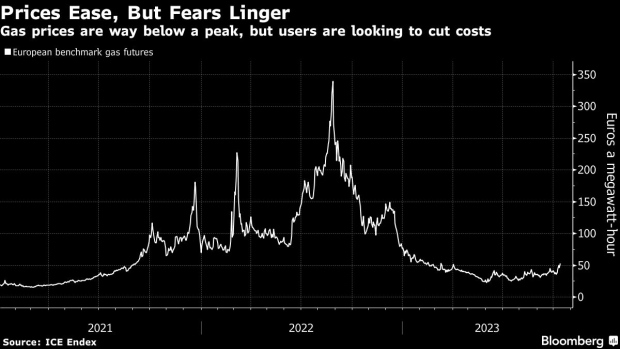

Users have become more dependent on LNG — particularly in Europe — after Russian piped flows were cut and prices soared to a record following Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine. While markets are now far below their peak, concerns still linger about further price spikes that forced many factories to shut down or relocate. With inflation still high, people are also looking for ways to cut costs.

UK chemical producer Ineos Group and Czech power producer CEZ AS were among those who moved into LNG last year, either through setting up a trading desk or making purchases. German chemical giant BASF SE recently struck a decades-long deal to buy US LNG. And more companies are considering the move.

“Purchasing LNG directly is part of a cost-cutting scheme,” said Ogan Kose, a managing director at Accenture. “If demand fluctuates and drops for the end products, having LNG trading capability would enable these consumers to divert cargoes and re-sell back to the market.”

And as well as locking in long-term supplies and prices, trading LNG could allow companies to even sell cargoes if needed, potentially for a profit. It’s possible for many of the companies identified by Accenture — in sectors from cement to paper and regions from Europe to Asia — to start trading quickly because they’re already set up in other commodity markets like coal or metals.

Entering LNG trading is worthwhile if users need at least 500,000 cubic meters a year as feedstock or to generate power, and if margins are high enough, Kose said.

Buying directly will probably make sense for a while. Wood Mackenzie expects price volatility to remain for a few years, and some forecasts point to LNG demand exceeding supply for the next two decades. That’s on top of persistent pressures for European industries — the International Monetary Fund this week cut its euro-area growth estimates and the region remains threatened by inflation, as well as any impact the Israel-Hamas war has on oil prices.

European gas futures have gained about 25% since the start of the month.

LNG Switch

Europe was last year jolted into replacing gas piped from Russia with LNG imported on ships from around the world, competing for cargoes with places like Asia. Buyers that had long worked with just a few suppliers suddenly had to deal with more counterparts.

Europe’s switch to LNG boosted its imports of the fuel by about 60% last year. The region is expanding terminals and regasification facilities to handle the extra volumes.

But moving into LNG can be more complicated. New entrants need access to terminal capacity, pipelines and tankers, enough credit for expensive cargoes and to know how much to secure on both a short- and long-term basis.

“It’s a different world for them, to come from pipeline gas and to switch to LNG,” said Chris Strong, a partner at law firm Vinson & Elkins LLP, which is working on a project involving the supply of regasified LNG to an aluminum smelter. “Relying purely on spot is risky and it’s volatile. The attractiveness for big industrials is to get long-term supply which they can plan around.”

Big industrial consumers are already inquiring about booking regasification capacity in Europe directly, Dunkerque LNG, which operates a French import terminal, has said. BASF is among those looking at expanding import terminals.

“If you can cut out the middleman and improve your own margins by purchasing LNG and then utilizing existing regas facilities and transportation capacity, then why would you not do that?” said Rob Butler, a partner at Baker Botts LLP, a law firm involved in energy transactions.

Even so, end users will still need the larger energy companies and trading houses with vast experience in supplying gas, for example to help meet sudden short-term requirements.

“To manage their own demand spikes, big consumers will still be dependent on global traders to buy prompt cargoes,” Accenture’s Kose said. “This need won’t go away.”

Buyers are moving into a trading at a time when there are questions over inking long-term deals for fossil fuels. While industrial users face pressure to decarbonize, they also need to secure enough energy — and gas is seen as a bridging fuel to a net zero world.

“A lot of people in the industrial space have to tread between climate goals and immediate needs for gas,” Vinson & Elkins’s Strong said. “That tension is going to continue.”

(Updates with prices in ninth paragraph, detail on law firm in the 13th)

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.