Jan 26, 2022

Jittery Markets Buckle as Powell Signals They Must Go It Alone

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Jerome Powell stuck to one message Wednesday, that the economy is strong and inflation must come down. Harried stock traders thought they heard another one: you’re on your own.

The result was another heart-rending turnaround in financial assets, with the S&P 500 giving up a gain of 2% for its biggest downward reversal in almost two years. Two-year Treasury yields notched the biggest one-day jump since March 2020 with a 13 basis-point surge. It was the third day of volatility as the Federal Reserve concluded its meeting with warring economic narratives playing out across increasingly thin liquidity.

For bulls, the problems started not with the Fed’s official communique but in Powell’s press conference, when he repeatedly batted away chances to assure investors the pace of interest rate hikes would be gradual. Instead, he said strength in the economy and employment should allow the Fed to be nimble, a level of confidence that investors interpreted as opening the door to increasingly restrictive policy.

“At least in today’s case, Powell’s desire for flexibility was viewed as hawkish, given his comments regarding inflation,” said Sameer Samana, Wells Fargo Investment Institute senior global market strategist. “It sounds like he is acknowledging the Fed is behind the curve and can’t commit to a path that won’t upset financial markets.”

Intense day-to-day volatility has dogged equities since early last week, when President Joe Biden said in a press conference that it’s the Fed’s job to rein in the fastest pace of inflation in decades, and supported the central bank’s plans to scale back stimulus.

Powell’s performance Wednesday accorded with that mission. He was asked about the possibility of “front-loading” rate hikes by doing them more frequently than once every other meeting. His answer focused on the strength of the economy without specifying a schedule for removing stimulus.

“We know that the economy is in a very different place than it was when we began raising rates in 2015. Specifically, the economy is now much stronger,” he said. “The labor market is far stronger. Inflation is running above our 2% target -- much higher than it was at that time. And these differences are likely to have important implications for the appropriate pace of policy adjustments.”

Absent were concessions that recent volatility in markets posed an immediate obstacle to tightening.

“I don’t really think asset prices themselves represent a significant threat to financial stability,” he said. “That is because households are in good shape financially, businesses are in good shape financially, defaults on business loans are low, and that kind of thing.”

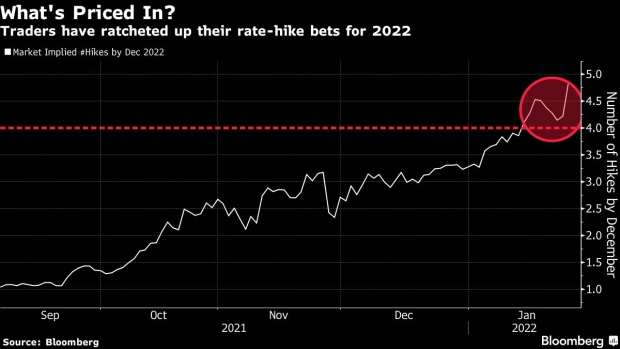

More than $5 trillion have been wiped out from share values this year as traders struggle to price the uncertain path of future interest-rate hikes. Markets had been pricing in four quarter-point hikes this year, but that edged toward five as Powell suggested the economy and labor market could withstand a faster pace if warranted. Highly valued tech shares wiped out gains that topped 3% at one point, while yields on 2-year Treasury notes climbed to 1.15%, the highest since February 2020.

“The Fed put is way out of the money,” said Peter Boockvar, chief investment officer at Bleakley Advisory Group, referring to a term that describes the central bank’s willingness to bail the market out of trouble. “Asset holders were reminded that we have many quarters ahead of monetary tightening and keep your seat belt on and if you didn’t have it on yet, better buckle up.”

Higher rates haven’t always snuffed out bull markets. The S&P 500 rose an average 5.3% in the 12 months following the first increase in 17 tightenings since 1946, according to a Ned Davis Research study on market returns and monetary policy. The pace of tightening, however, makes a stark difference: The equity benchmark fell 2.7% on average during faster rate hikes while rising 11% during slow ones.

While the Fed has often seemed to come to the aid of investors in the past, the current market backdrop makes doing so now challenging. Even accounting for its recent travails, the Nasdaq 100 trades at 5 times the value of its constituents’ sales, a distance with few precedents other than during the dot-com bubble. At its height, the S&P 500’s price-earnings ratio topped 30. While it has since contracted to 24, the multiple is still 20% higher than its 10-year average.

“Powell said that the Fed’s focus has always been on the underlying economy, and a byproduct of that has been inflated asset prices,” said Max Gokhman, chief investment officer at AlphaTrAI. “But now that inflation is here and real while labor markets have slack, it’s time to focus on fighting that fire, and if that burns euphoric bulls then so be it.”

The Fed did stop short of making a surprise move that surely would’ve roiled risk assets. Some investors had expected the central bank to be so focused on inflation that it would halt bond purchases at this meeting and potentially signal a 50 basis-point increase in March. It did neither.

Concern about tighter policy is creating pressure in a market where traders are already finding it difficult to buy and sell stocks without having an outsize impact on share prices. A measure tracked by JPMorgan Chase & Co. showed market liquidity has shrunk to the lowest level since the pandemic crash during March 2020.

Worried investors are flocking to the most liquid instruments in the investing world to navigate the market turmoil. Trading across exchange-traded funds spiked this week to a record, data compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence.

All the data “are pointing to severe deterioration in liquidity conditions this year,” JPMorgan strategists including Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou wrote in a note. “This poor liquidity picture raises the probability of large equity market moves either way but it does not necessarily imply capitulation.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.