Jul 8, 2020

Justin Trudeau's gaping deficit begins new era of debt for Canada

, Bloomberg News

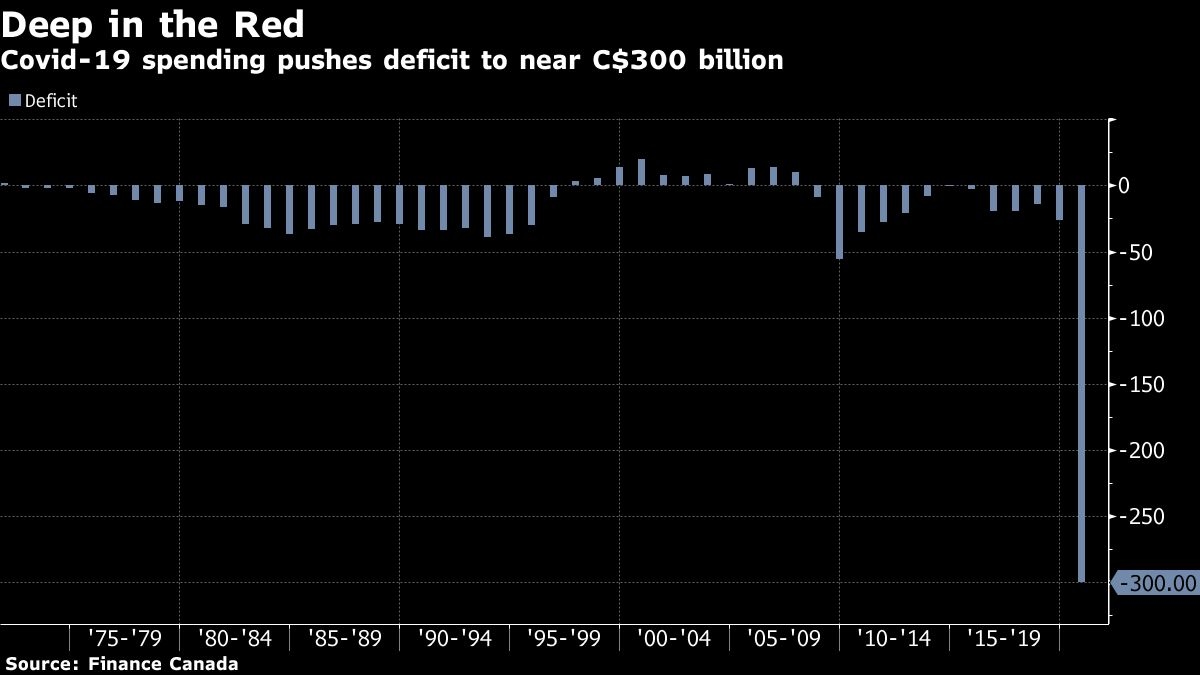

Canada facing $300 billion+ deficit

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is set to release his first estimate of the full cost of the effort to buffer Canada from its deepest recession since the 1930s.

Trudeau’s finance minister, Bill Morneau, will provide a fiscal update Wednesday that’s expected to show a current-year deficit of more than $300 billion ($221 billion), or about 14 per cent of economic output, BNN Bloomberg television said. The gap last year was about 1 per cent of gross domestic product.

No other major advanced economy tracked by the International Monetary Fund is expected to record a larger one-year fiscal swing in 2020.

While the massive shortfall has broad political support, it’s dramatic departure for a country with a longstanding aversion to debt and leaves Canada with the prospect of running large deficits for years to come. Morneau, the first finance minister to oversee a credit rating downgrade in 25 years, is under pressure to provide at least cursory assurances the government will return to a more fiscally prudent path once the coronavirus crisis has passed.

The question is “what the next one, two, three years are going to look like and what the appetite is going to be to pull that deficit back down,” Robert Kavcic, senior economist at BMO Capital Markets, said by phone, adding it may be too early for the government to give much guidance.

“We decided to take on that debt to prevent Canadians from having to do it,” Trudeau said at a news conference Wednesday morning in Ottawa. If the government had not provided income support, “what would Canadians have done? They would have loaded up their credit cards. They would have scrambled to try and find ways to pay their bills and pay their groceries and figure out how to care for their loved ones.”

Debt Management

It’s unclear whether Morneau will provide forecasts beyond the current fiscal year.

The figures will be released around 1:40 p.m. in Ottawa, when the finance minister is due to deliver the “economic and fiscal snapshot” in parliament.

He’s expected to announce some details around plans to extend debt duration to lock in historically low interest rates, one senior government official told Bloomberg, on condition they not be identified.

Trudeau’s government has already budgeted direct COVID-19 spending of $174 billion, almost half to finance a $2,000-a-month payment to those who’ve lost jobs or income as a result of the economic crisis. More than 8 million people have received at least one payment under the Canada Emergency Response Benefit.

Before the crisis, Morneau had projected a budget gap of $28 billion. Adding in lower tax revenue and other emergency spending brings the total shortfall to near the quarter-trillion dollar mark. There’s a risk it could blow out even wider if the current programs are extended.

The sudden gaping hole in the government’s balance sheet has already prompted Fitch Ratings to downgrade Canada’s AAA debt assessment, a blow to a country that took pride in its top status. The last downgrade in 1995, when Moody’s Investors Service Inc. cut to Aa2 from Aa1, and launched the Liberal government of the day on a years-long campaign back to balance.

A deficit-fighting mindset remained in place for years, until Trudeau rode an anti-austerity platform to power in 2015 and again last year. Even then, his deficits were modest, hovering at less than 1 per cent of GDP.

Road Ahead

The Canadian leader, ironically, will probably spend the rest of his political career reining in government spending. The trick will be to phase out COVID-19 programs without creating a shock to the economy. Morneau’s fiscal snapshot may provide details on how the government plans to proceed.

Possibilities include retaining the income-support program longer, or pushing individuals onto employment insurance. Another outstanding issue is how the government plans to expand eligibility for wage subsidies, allowing more companies and organizations to qualify.

Trudeau, whose party lacks a majority in parliament, is facing pressure from his left to prolong government aid. “We’re not out of this pandemic yet. Canadians - and our economy - need the supports to continue,” Jagmeet Singh, leader of the New Democratic Party, said in an email.

On Trudeau’s right, questions are growing about the effectiveness of some of the spending, along with calls for more transparency and the need to get Canadians back to work. “Some of this spending is starting to look a bit indiscriminate,” Alberta Premier Jason Kenney told Bloomberg News in an interview last week. “And I really think we need to be careful not to disincentivize people from going back to work.”

Fast Cash

But few outside politics blame Trudeau for the large deficits. The quick release of massive amounts of cash directly to Canadians has largely been lauded by economists, who claim the situation would have been much worse without it.

Another saving grace is that Canada has plenty of fiscal capacity, with pre-pandemic debt to GDP at around 30 per cent, the lowest ratio in the Group of Seven. Borrowing costs are also at all-time lows, which should keep a lid on public debt charges.

The IMF is forecasting a 6.2 per cent economic contraction for all of 2020, followed by 4.2 per cent expansion in 2021. That would be in the middle of the pack of advanced economies.

Yet, future waves of COVID-19 will probably erode Canada’s fiscal capacity further. As the Fitch downgrade illustrates, there are limits to how high the nation’s debt can rise without a backlash.

--With assistance from Kevin Orland and Erik Hertzberg.