Mar 8, 2022

Memories of post-COVID melt-up haunt anyone selling stocks now

, Bloomberg News

Investors should be buying during times of peak fear: Robert Arnott

Institutional investors are offloading equities to retail buyers in a traumatized market. While similarities between now and the bottom of the coronavirus crash may end there, memories of how that episode played out are proving hard to shake.

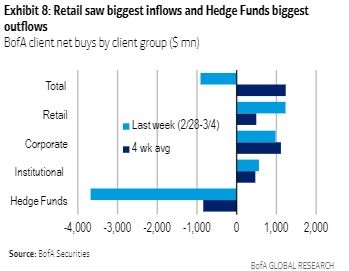

Despite breakneck volatility and harrowing images of war, retail traders just plowed money into the equity market for a ninth straight week, according to Bank of America Corp. client data. That’s a stark contrast to the firm’s hedge fund clients, which last week sold US$4 billion of stocks, the most on record. Same thing on Morgan Stanley’s trading desk, where professional speculators have been cutting equity exposure, alongside relentless buying from amateurs.

Who exactly constitutes the smart money on post-pandemic Wall Street is a point of debate after mom and pop day traders dove into stocks as they were bottoming two years ago. While a single example of prescience doesn’t imply the retail crowd is right this time, the fortunes minted at the bottom of that crash have constituted powerful psychological conditioning during two years of buy-the-dip euphoria.

BofA data shows that S&P 500 returns following periods of big retail inflows have been above average, while the index’s performance is subpar post-retail selling. When compared with the hedge funds’ record, the retail crowd acts as a “slightly better” indicator for future returns.

“This is just an extremely dynamic situation, and if peace breaks out, there’s not going to be enough time to react,” said Peter Mallouk, president of Creative Planning, which has about US$230 billion in assets under management. “It will be as if when we got news of the Fed intervention and how quickly the market recuperated.”

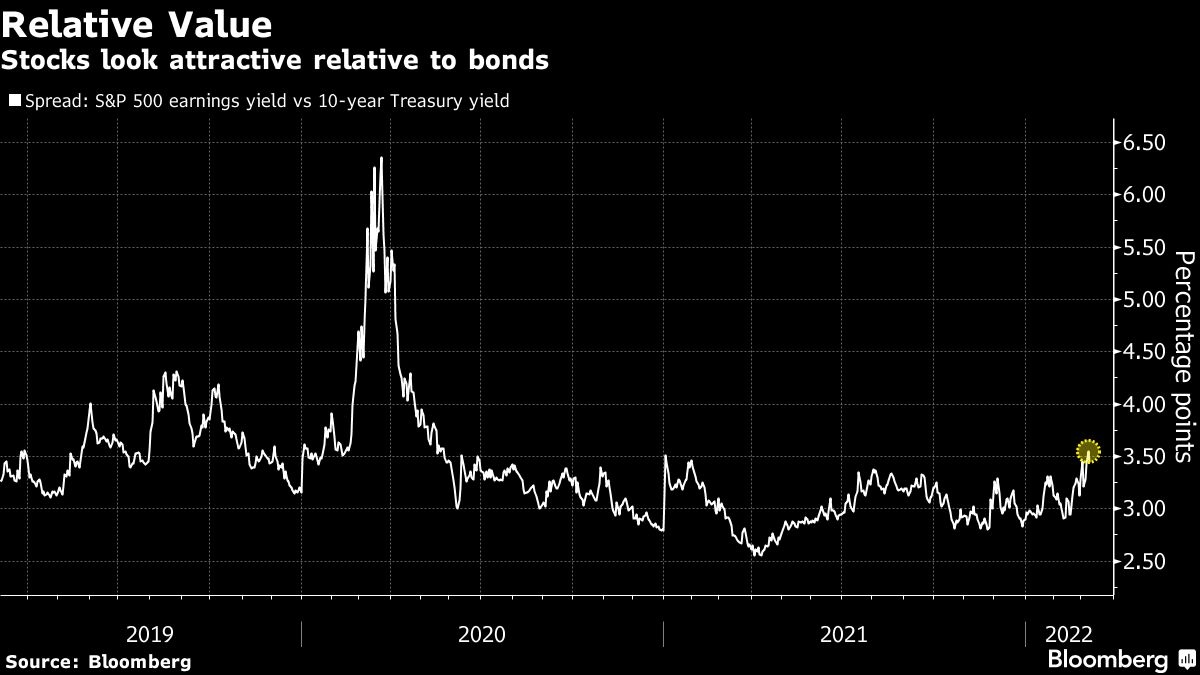

A question related to the debate around who has it right at present is whether stocks have fallen enough to become bargains. Based on forecast earnings, the S&P 500 looked much cheaper than it was in January. At 18.3 times profits, the index’s valuation is at the lowest level since the month right after the 2020 pandemic crash and was in line with its five-year average.

The valuation case turned equally favorable when measured against the bond market. With 10-year Treasury yields hovering below 2 per cent, the S&P 500’s earnings yield -- a reciprocal of its P/E ratio, pointed to the highest equity premium since the early days of this bull market.

“You would have pretty much doubled your money in just two years if you had bought that dip after the COVID selloff,” said Christoph Schon, senior principal of applied research at Qontigo. “Maybe now those who didn’t buy at that point, they’re trying to get in now in the hope that we will see a similar rebound.”

While the dip-buying strategy has worked consistently well since the last bull cycle began in 2009, skeptics are quick to point out this episode may be different. During the past week, at least three Wall Street strategists slashed their 2022 year-end targets for the S&P 500, with recession risk among the concerns cited.

Thanks to inflation running at a four-decade high, the Fed has ceased its role as the bull market’s most reliable ally. In fact, the central bank is expected to raise interest rates this month for the first time in three years, creating pressure on equity valuations. The runup in commodities prices from oil to nickel since the war began has only exacerbated pressure on the Fed to corral runaway price gains.

Granted, history shows the market impact from military events was often fleeting. But with the war in Ukraine leading to sanctions against Russia, uncertain economic prospects challenge every conviction.

“If we woke up tomorrow and Russia left and Ukraine was left to its own devices, I think you’d see a big market rally but I don’t think we’d see a sustained multi-year profits boom,” said Brian Nick, chief investment strategist at Nuveen. “COVID did so many things to scramble how people behave, how corporations make money, how policy makers work -- I just don’t think we’re going to see the same collection of half a dozen really stiff tailwinds helping profits, helping the markets.”

And while day traders are free to load up on beaten-down stocks, pros may have been constrained by their risk-management frameworks where rising volatility often necessitates the unloading of portfolio assets -- selling longs and covering shorts.

Last week, when the S&P 500 dropped in the third week in four, hedge funds tracked by JPMorgan Chase & Co. cut gross leverage -- a measure of risk appetite that takes into account both bullish and bearish equity wagers -- at the fastest rate in more than a year. Meanwhile, the firm’s data pointed to continued buoyant retail purchases.

For anyone who experienced the bursting of the dot-com bubble, today’s persistent retail buying likely brings flashbacks to the days when a long spell of momentum chasing led to an unsustainable market top. While many factors differ now versus then, some market watchers say the S&P 500’s bottom will only form when the YOLO crowd capitulates.

“This group has a tendency of making investment decisions that are influenced by emotions,” said Adam Phillips, managing director of portfolio strategy at EP Wealth Advisors. “It’s important to acknowledge that the average retail investor has a different approach, or process, to buying stocks. This explains why many investors track measures of broad retail investor sentiment and in some cases use them as a contra-indicator.”