Dec 6, 2022

Repo Pressures Join Fed Hikes in Driving Up Dollar Funding Costs

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Short-term dollar borrowing costs are being driven higher by more than just the expectation that the Federal Reserve will keep pushing up its overnight benchmark. The effects of central bank balance-sheet reduction are finally being felt now too and there’s probably more to come.

Benchmark hikes are, of course, the biggest driver behind the surge in front-end market interest rates this year: the fed funds target has risen by 375 basis points and has at least another 100 to go before it tops out, if traders are right. But in addition to that, “small but significant shifts” are taking place in money markets that’s creating extra pressure, according to Bank of America Corp. analysts Mark Cabana and Katie Craig.

The change, they say, is becoming evident in the market for overnight repurchase agreements, which are one-day loans collateralized by Treasuries. Repo, as it is known, is a critical part of money markets and becoming increasingly so, as it underpins the Secured Overnight Financing Rate. That’s the benchmark that’s favored by officials to take over from the soon-to-be-retired London interbank offered rate, and is already becoming a key component for a lot of borrowing.

Repo rates are being pushed up at the moment relative to fed funds because there’s now more demand for borrowing in that particular market. And the main reason for that is that banks -- and others -- have a bigger pile of Treasuries on their balance sheets than they used to, while there’s also less cash out there trying to borrow them.

When the Fed was buying bonds to keep rates low -- a process known as quantitative easing -- relative demand for repo trades dropped. The financial system was swamped with cash and the supply of available bonds declined, dragging down repo rates. That even continued through the early stages of so-called quantitative tightening, which began earlier this year, because there was such an abundance of cash and an ongoing shortfall of available Treasuries.

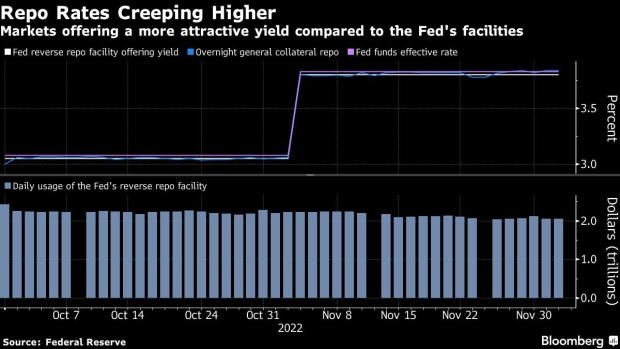

This dynamic vexed money-market funds and others that can only invest in the shortest-dated assets like Treasury bills and repurchase agreements, pushing them to park over $2 trillion in a facility at the Fed instead.

But now some of those funds are shifting money away from that facility because they can earn more in the repo market. At the end of November, the SOFR benchmark -- in effect a proxy for repo because it’s based on market rates -- fixed at 3.82%, or 2 basis points more than the Fed’s reverse repo facility. It was the first time the gap had been that large since March 2021.

A couple of basis points seem like a small amount, but it looms large for banks and other institutions after years in which such costs were significantly below key benchmarks. Perhaps more salient is the fact that these rates are finally rising -- and could go further still.

The Bank of America analysts say the increase in repo rates has likely been driven by a jump in the amount of Treasuries on securities dealers’ books -- a trend they expect to keep putting upward pressure on rates. That has been notable in dealer holdings of short-term bills, where they had net long positions of $55.1 billion in the week through Nov. 30, the most since March 2, New York Fed data show.

“Collateral has recently started to overwhelm cash & will keep doing so until QT ends,” Cabana and Craig wrote in a note to clients on Monday. “We have long been anticipating this shift in 2H ‘22 and now see clearer evidence of it.”

The move is likely to continue through next year as the Fed continues the process of shrinking its bond holdings, which the analysts said will drain an additional $1 trillion in liquidity from the system. At the same time, the supply of Treasury bills and debt from the Federal Home Loan Banks is also expected to increase.

Still, the rise in front-end rates won’t be a straight line because the Treasury Department’s moves to prepare for a standoff in Congress over the debt ceiling limit will likely constrain bill supply until a resolution is reached, according to the strategists. Once a deal is struck -- potentially late next year -- it will unleash a deluge of bills as the Treasury rebuilds its cash balance and funds ongoing deficits.

“The debt limit will create noise,” the Bank of America analysts wrote. “But bill supply will surge in ‘23.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.