Jun 23, 2023

Stubborn UK Inflation Triggers a Mortgage Crisis for Millions

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Rising mortgage payments are squeezing the finances of millions of borrowers in Britain, threatening to undermine household spending and the broader economy.

The dream of a soft landing that would have the Bank of England squeeze out inflation without condemning the country to a recession looks increasingly remote. Inflation is cooling only slowly, forcing the central bank to go hard on Thursday with a bigger-than-expected hike that took the key rate to 5%.

Markets believe the only way to curb prices will be to go even further and push rates to levels not seen in more than two decades.

After falling energy prices offered a brief moment of optimism, the UK has been pulled back into the political and economic throes of a cost-of-living crisis. The squeeze is eating into incomes, taking away money that might otherwise be spent in stores, bars and restaurants, creating a drag on an economy forecast to grow just 0.2% this year. Only Germany is expected to have a weaker performance among major developed economies.

The effect on the mortgage market of the central bank tightening has been dramatic. Since March last year, the average two-year fixed deal has trebled to 6%. For homeowners coming off fixed deals, it will be painful.

At current rates, the cost of the average home loan will rise by £280 a month, the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates. That’s over twice the increase in average energy bills seen after the invasion of Ukraine. Over the next year and a half, 2.4 million households are at risk as their fixed deals expire, according to UK Finance, of which 800,000 will be in the coming six months.

“It’s tough for UK households,” former BOE Governor Mark Carney said in a Bloomberg interview. “They’ve been hit by an energy shock, the price of food rising rapidly, and mortgage rates if they have a mortgage. So it’s exceptionally tough.”

Andrew Bailey, his successor, acknowledged the difficulties on Thursday, but added that tighter monetary policy is necessary.

“I know this is hard,” he said. “Many people with mortgages or loans will be rightly worried about what these changes mean for them. But if we don't raise rates now, higher inflation could stay with us longer.”

Bailey also noted the strong labor market and resilient demand, which was on display in better consumer confidence figures on Friday as well as retail sales that beat expectations. In less positive news, business surveys showed UK manufacturing shrank in June and services — the biggest part of the economy — cooled more than forecast.

Politically, slow progress on inflation is undermining a key pledge of Prime Minister Rishi Sunak — to halve the rate this year.

For Keir Starmer, leader of the opposition Labour party, it’s an open goal. He’s branded the cost shock “the Tory mortgage penalty” and stories like the one he told Parliament this week of “James,” a police officer from Selby whose mortgage bill has gone up by £400 a month, will be commonplace. James is selling his home, downsizing and moving his children into a shared bedroom.

Meanwhile investors are setting off recession alarm signals in the bond market, and worries about growth are so pronounced that even a half-point rate hike wasn’t enough to lift the pound on Thursday.

With housing at the heart of the economic pain, homebuilder stocks have fallen almost 20% from a recent peak in early May, and are at their lowest this year. Berkeley Group Holdings Plc said this week that current trading suggest home sales will fall 20% this fiscal year and HSBC issued a slew of downgrades on the sector.

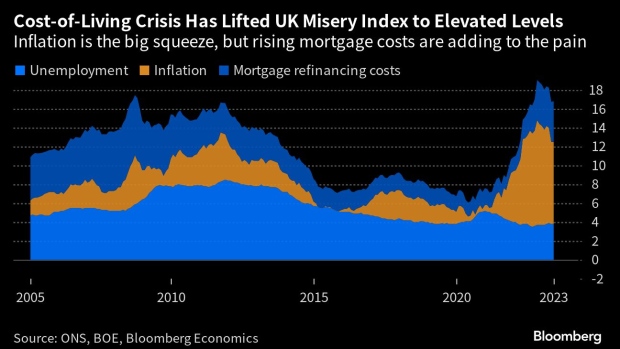

A misery index by Bloomberg Economics that combines inflation, unemployment and mortgage costs is at elevated levels, with the mortgage component growing in impact. And firms reliant on upbeat consumers willing to spend are worried about the impact on their business.

“It’s clear that purse strings will be tightened once again in the coming months,’’ said Emma McClarkin, chief executive of the British Beer and Pub Association. “We need the government to face the reality that inflation is still incredibly high and the critical impact this has on both consumers and the businesses they choose to spend their money with.”

The mortgage squeeze comes on the back of two years of declining real incomes, and households are already cutting back to make ends meet, official data shows. More people are shopping for discount items at the supermarket, and retail sales figures show volumes falling as prices rise. Plans for renovations and repairs are being scrapped, and cleaners and nannies are less in demand.

It is not just borrowers who are suffering, but tenants too. Landlords are passing on higher costs and rents are rising at 5% on average compared with less than 3% a year ago.

Read More on the UK:

- Britain Is Adrift, and the World’s Executives Are Alarmed

- UK National Debt Breaches 100% of GDP for First Time Since 1961

- Warnings of Mortgage Crisis Overblown, Says Top BOE Official

While tales of individual misery are inevitable, the broader economic impact may be limited because many households remain on fixed deals that will only roll off slowly over time, rather than hit in one big crunch. Property-price gains have improved loan-to-value ratios, which will also help homeowners when they refinance. Plus, a growing share of homeowners — 36% — are mortgage free and so insulated from rate hikes.

Rob Wood, chief UK economist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, estimates that were BOE rates to reach 5.5% the impact through higher mortgage costs to consumption would be 0.5%, if taken on its own. All else equal, that would translate into a 0.3% hit to GDP. Had today’s mortgage market, with 85% of deals on fixed rates, more closely resembled 2008, when just half were fixed, consumer spending would have shrunk 1.5%.

David Roberts, chair of the BOE’s court of directors, is also relatively sanguine, saying borrowers have been tested against higher rates and fixed deals give them time to prepare by tucking away savings if they can.

The government is facing calls, including from its own benches, for mortgage aid. On Friday, Chancellor Jeremy Hunt will tell lenders to offer struggling borrowers forbearance by extending terms or switching to interest only deals.

UK Finance, which represents the banking industry, said Thursday that lenders are “ready to support customers who are feeling the strain.”

Hunt has so far refused to undermine the BOE by caving into the calls to provide support. He doesn’t have the money, as higher rates have added to government debt servicing costs, but doing so would only backfire anyway.

“We are making sure we are fiscally prudent, not exacerbating inflation with big spending,” Gareth Davies, exchequer secretary to the Treasury, told Bloomberg Television.

But there are individual struggles. Almost 80% of low-income private renters are going without at least one essential, as are 73% of low-income mortgage holders, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation found. StepChange, a debt charity, said one in 10 mortgage holders are in problem debt.

Still, there is so far little sign of widespread household distress. Payments in arrears are no higher than they were last year and repossessions are below pre-pandemic levels.

And according to weekly Office for National Statistics figures, the cost-of-living crisis has gradually eased since April. But among those that say life is getting harder, 23% cited rent or mortgage costs.

The big risk is that depressed consumption causes job losses that catalyze a worse economic crisis. Dan Hanson, senior UK economist at Bloomberg Economics, reckons 6% rates would be enough to cause a 2% drop in output.

The BOE is reluctant to say it, but a recession may be necessary to get rid of inflation. According to Hanson, that “increasingly looks like the only path available to the central bank.’’

“That is the transmission mechanism of monetary policy, after all,” said Erik Britton, chief executive of Fathom Consulting.

--With assistance from Neil Callanan, James Hirai, Francine Lacqua and Joel Leon.

(Updates with business surveys, homebuilder stocks.)

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.