Apr 28, 2021

Super League dream won’t die for two arch enemies united by debt

, Bloomberg News

Largest lever for revenue is winning: Blue Jays CEO on the business of baseball amid COVID-19

The animosity between Spain’s two biggest and most successful soccer clubs cuts through civil war, dictatorship and identity politics off the field, and bitter competition for global stars on it.

After midfielder Luis Figo defected to Real Madrid in 2000, Barcelona fans famously threw a pig’s head onto the pitch when he was taking a corner kick. More recently, Barcelona President Joan Laporta provocatively plastered his face on a billboard near Real’s stadium this year that read “hoping to meet again” as part of his election campaign.

The two clubs, though, are now united as the last holdouts to defend the existence of the short-lived European Super League, which collapsed last week just 48 hours after its creation following a political and public uproar across the continent.

The alliance between the two arch enemies underscores how even though the Super League may be over before it even began, the precarious state of soccer’s finances will ensure that the idea of a breakaway will live on.

Both clubs say a new league is vital after a decade in which they dominated the UEFA Champions League—winning a combined six titles in a competition they now are seeking to abandon—to guarantee enough money comes in. Unlike their would-be Super League peers, Real and Barcelona aren’t backed by tycoons, private equity firms or Gulf wealth and are owned by fans.

“Pressure on clubs to take more control of their finances has been building for years,” said Maria Rua Aguete, a senior director at London-based media research consultancy Omdia. “While the Super League is dead, UEFA was shaken to its core, and it is likely that changes in the compensation system will be made to reduce the instability and the uncertainty of income.”

Read More: Europe’s Soccer Coup Was Foiled by an Uproar and a French Snub

Of the two, Barcelona is in more urgent need of remedial action, something Laporta promised to take as he was elected president of the Catalan club in March.

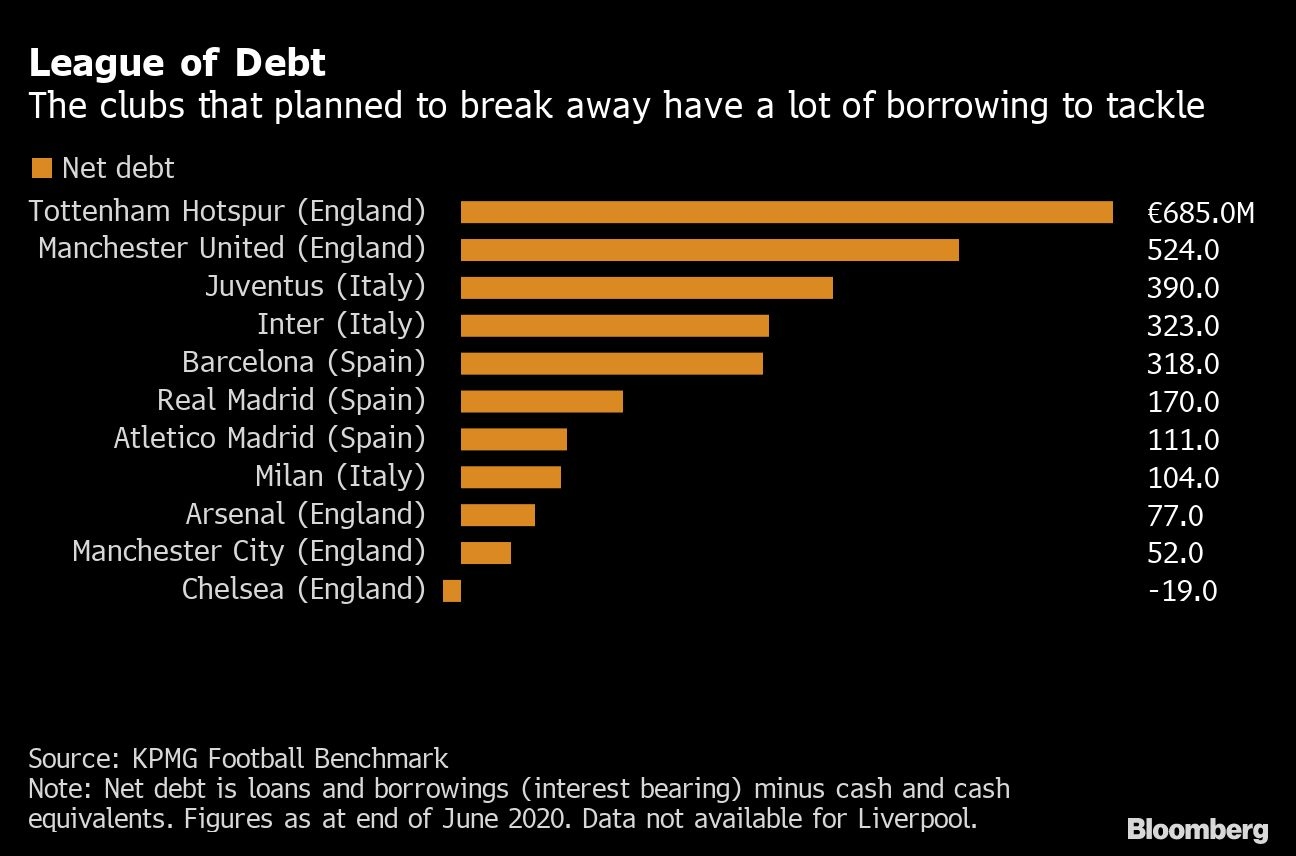

Barcelona has recorded the highest revenue in soccer for the past two years, but it also has the highest level of borrowing. As of June 30, its net debt totaled 488 million euros (US$590 million), more than twice what it was a year earlier. It also had to seek waivers on debt covenants from a group of investors earlier this year.

The team is now calling on the sport to explore other ways to create a new competition. “Barcelona appreciates that a much more in-depth analysis is required into the reasons that have caused this reaction in order to reconsider,” it said in a statement last week.

At Real Madrid, Chairman Florentino Perez prided himself of having fixed the club’s finances. But debt ballooned during the pandemic after games were canceled and then played in empty stadiums. Between April and May last year, as lockdowns started, the club drew 205 million euros in bank loans to compensate for lost income. That pushed net debt to 241 million euros, almost 10 times a year earlier.

A billionaire who made his money in construction, Perez was the main architect behind the Super League and nominally is still its figurehead. His main financial adviser is Madrid-based Key Capital Partners, which was in charge of managing the design of the league. Anas Laghrari, a partner at Key who has known Perez since childhood, was slated to be secretary general.

Perez says the new tournament is necessary to save soccer, but also as part of the club’s tradition as a pioneer of European competition in the 1950s. Real Madrid has won the Champions League or its precursor, the European Cup, 13 times, more than anyone else.

“What we have done has been to give ourselves a few weeks to think given the hostility with which some people, who don’t wish to lose their privileges, have manipulated the project,” Perez told Spanish newspaper As last week.

The 12-member Super League crumbled after the six English clubs started withdrawing, spooked by the vitriolic reaction from fans and the government. The company formed by the breakaway still exists, though. Clubs are wary they could be fined as much as 300 million euros by formally quitting and be open to legal action, according to a person familiar with the concerns. Still, penalties and lawsuits are unlikely to happen, the person said.

The dream of keeping the league alive hinges largely on an injunction issued by a commercial judge in Madrid on April 12. It ordered UEFA, European soccer’s governing body, to refrain from sanctioning the participant clubs. The organizers see the order as assurance that they can continue to negotiate on plans, according to a person familiar with the talks.

“Current European competitions are not stable,” said Rua Aguete. “To compound this, the huge costs incurred during the pandemic, with wages due and stadia closed, has led to a situation where the big clubs feel their current financial model is unsustainable.”