Dec 14, 2020

The future of money: After the pandemic, will you have your own 'financial pandemic'?

The future spending habits of Canadians post-pandemic

The global pandemic changed everything in 2020. Now it is going to change everything forever. This is part of "The Future of" series, in which BNN Bloomberg looks at what is next for our transformed economy and daily lives.

Jahmeelah Gamble is honest about how she has been plodding through the days of the pandemic.

"The app that I use to track my mental health is called Zara," she recently tweeted, referring to the clothing retailer. "Based on the amount of orders I've placed in the last month, it's safe to say that I'm [sad emoji]."

The 33-year-old Mississauga, Ont.-based speaking coach admits that online purchases and strings of daily take-out are coping mechanisms, a temporary antidote to stress.

“I’ve reached a point where nothing feels good. You’ve got money but you can’t go out and spend it. You can’t celebrate. The only way to feel connected to the outside world is to buy something online,” she says. “With COVID, we’re not in control of things. We can’t do what we want to do; but we can buy what we want to buy. It makes me feel like things are still normal.”

With the pandemic, our world seemed to change overnight and suddenly, the state of our finances became more salient, more pressing, and for many, perilous. Some of us have adopted behaviours when it comes to spending, saving, borrowing and investing that are unique to this time — ranging from helpful to harmful.

But with officials touting light at the end of the tunnel, how will the pandemic have affected our money habits and financial values on the other side of it? Will the trauma of financial tumult change us forever? More importantly, how can we leverage the lessons for our own good?

According to many surveys, Canadians have become more stressed about money (among a litany of other worries); a FP Canada report released this past summer, for instance, revealed that almost half of respondents have lost sleep over their finances.

All of this anxiety changes your brain function and leads to irrational money decisions, explains David Lewis, chief client officer of BEworks, a behavioural economics consulting firm.

- Year-end tax tips to consider in the COVID era

- Pattie Lovett-Reid: Three smart money management moves to make before year-end

- Canadians show increased interest in high-interest car title loans amid recession

RELATED: PERSONAL FINANCE

It muddies our ability to process complex information, which is required when making financial decisions. It also causes us to focus on the now, rather than the future. This could take the form of retail therapy, as it may be in Gamble’s case and if I too, am honest, in my household’s case. This could also take the form of accumulating more debt without a plan to pay it back.

As of Oct. 31, Canadian banks provided mortgage deferrals or skip-a-payment options to almost 800,000 Canadians and processed more than 478,000 credit card deferrals, although most of those programs have winded down. Canadian households owed an average of $1.71 for every dollar of disposable income in the third quarter, up from $1.58 in the previous quarter, according to Statistics Canada.

“We’re engaging in these bad habits. We’re building up debt,” Lewis says. “But when the global pandemic is over, will you have your own financial pandemic?”

DANGERS OF HOARDING

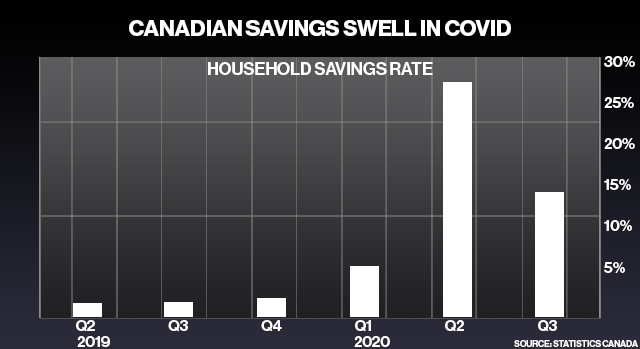

While we may be awash in the same storm, we’re in different boats. Some Canadians are faring better than others. Despite being in a second wave of the pandemic, consumer spending was up slightly in November from last year. And with less to spend on, households have saved in excess of $150 billion more than normal times (the savings rate hit a record 27.5 per cent in the second quarter of the year), according to a Bank of Montreal report.

A Bank of Nova Scotia poll revealed that 61 per cent of Canadians who are saving more are opting to build up an emergency fund. While saving for the unexpected and for other goals is prudent, hoarding cash is not.

“The Depression generation to this day doesn’t want to throw things away because they remember the incredible scarcity during that time,” Lewis says. “Maybe this generation is going to see volatility in the market place and say, it’s too dangerous, maybe I’m going to avoid it.”

People already tend to be shortsighted and risk averse when it comes to investments. “If you pull your money out of an investment account and stick it in a savings account, you’re not going to be beating inflation. If you avoid risk, you’re avoiding returns.”

Behavioural experts say that recognizing that you may be thinking irrationally about money is half the battle. The next steps involve setting up a system to keep yourself in check. For example, Lewis says a colleague deliberately locked himself out of his online investment account to prevent himself from obsessively looking at it. Another strategy would be to consult your peers or a coach. During the market crisis in March, investors en masse contacted their advisors in panic.

“I’ve literally had to walk people off the ledge,” says Jackie Porter, a certified financial planner with Carte Wealth Management Inc. “Intervention is crucial. Especially during this time, people need someone to talk through their fears, walk through their plans to help them see the horizon. It’s getting people to think of the future and that’s not tomorrow. It’s not five years from now. It’s not even 10 years from now.”

"The Depression generation to this day doesn’t want to throw things away because they remember the incredible scarcity during that time."

There is good scientific evidence that people are adaptive and five years from now, even 10 years from now, we may have adjusted back to our lives, barring any financial damage that has been done, some hypothesize.

“I’m skeptical that a lot of the changes will stick and persist. I think people will be eager to get back to what they were doing before,” says Douglas Porter, BMO’s chief economist.

And what were we doing before?

“If we go back to the good old days of a year ago, the biggest concern in Canada was the state of household finances.The flow of savings was quite low. Household debt was relatively high.”

We’ll have these concerns, yes, but we’ll also have hindsight. But it’ll take conscious effort to hold onto epiphanies and helpful money habits as we fall back into old and familiar routines.

“The bigger question is what sort of values, priorities and behaviours will remain salient in people’s minds?” says Hal Hershfield, associate professor of marketing and behavioural decision-making at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management.

“A lot of people are surprised at what sort of things they’re valuing now and what sort of things they can do without.”

Melissa Leong is the author of the award-winning finance guide Happy Go Money.