Dec 9, 2022

The Pound Went on a Wild Ride Close to Dollar Parity in 2022

, Bloomberg News

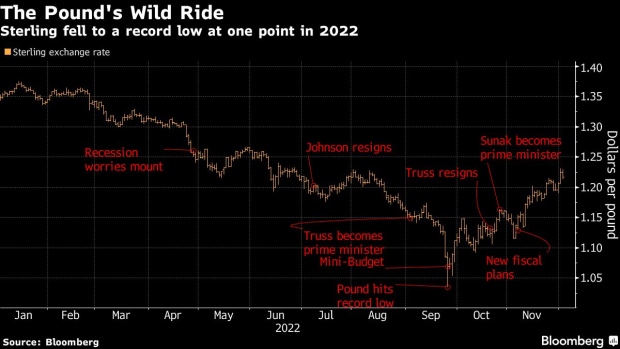

(Bloomberg) -- Three prime ministers, four finance ministers and one ill-fated budget dragged the pound within an inch of parity versus the US dollar in 2022.

It was a wild ride for the currency, which suffered as political chaos engulfed the UK throughout the year. But everything went into overdrive in September, when the government’s gamble on a huge tax giveaway backfired, investors dumped sterling and UK bonds, and the Bank of England was forced to intervene to prevent a gilt market crash.

As the turmoil unfolded, sterling was being compared to an emerging-market currency and the UK’s long standing credibility on international markets was coming undone. Now, even with the worst past, it looks poised to remain weak as the country embarks on a much-needed repair job on its economy and finances.

Strategists and portfolio managers expect it to stay between $1.10 and $1.30 for some time. The options market shows there’s a 40% chance the currency will be hemmed between those levels over the next two years, marking its weakest-ever trading range.

“Ever since the Brexit vote we’ve always called sterling a bit of a ‘basket-case’ currency, in that it follows growth much more closely than rate differentials,” said Eva Sun-Wai, fund manager at M&G Investment Management, whose Global Macro Bond Fund has been short the currency for most of the year. “And if we are coming into a very steep contraction and our growth is worse than other regions, that will hurt.”

The pound, which opened the year at $1.35, dropped to a record-low $1.035 on Sept. 26, just days after the disastrous mini-budget. Ultimately, the reverberations through the currency and gilt markets forced the government into a u-turn and led to the demise of Liz Truss as prime minister.

A new leader, Rishi Sunak, has kicked off off a more austere fiscal program, and the pound has recovered some ground. It’s currently trading around $1.20-$1.23, well above September’s lifetime low, but has been left battered and bruised by its annus horribilis. In addition, the UK still faces long-term imbalances and underwhelming economic growth, which will limit sterling’s upside.

New Range

The expected new range continues a long-term downward trend for the currency. Its average in the five years before the 2016 Brexit vote was roughly $1.59. And in the five years before that, around $1.76.

“The image of the UK has been tarnished by Brexit, by the political turmoil and the episode we saw in September,” said Chris Iggo, chief investment officer of AXA Investment Management’s Core unit. “As a global investor you need to be convinced of the value opportunity in order to increase your exposure to the UK. They just don’t see that at the moment.”

How overseas investors view the UK is crucial, given that the country needs outside capital to fund its current account deficit.

For years, the UK has lived beyond its means, storing limited savings and looking overseas to borrow to keep its funding needs in balance. That’s been an ongoing risk for its currency and bonds, which can sell off if confidence is shaken, as they were after Truss’s mini-budget. The weaker currency can also, however, help to bring supply and demand into balance by increasing exports and reducing imports.

The Bank of England warned recently that the size and make-up of the external balance sheet make it “vulnerable to reductions in foreign investor appetite.” Former Governor Mark Carney previously summed it up by saying the country is reliant on the “kindness of strangers.”

The currency needs to stay “relatively weak,” while the UK economy battles through a slowdown and rights its fiscal position, said Aaron Hurd, portfolio manager at State Street Global Advisors. He sees that level around $1.15 to $1.20.

The chaos of the Truss premiership supercharged a currency decline that was already in motion because of dollar strength. But domestic economic conditions, as well as politics, also played a part. Truss’s predecessor, Boris Johnson, was forced to quit over the summer after a litany of scandals that led to a mass resignation by members of his government.

Even after the recent rebound, sterling is still down almost 10% since the end of 2021. That ranks among its worst ever performances, rivaled only by the years of the Brexit vote, the 2008 financial crisis and Black Wednesday in 1992.

The volatility this year has been a turn-off for investors, and luring foreign capital back could require higher rates, according to Morgan Stanley FX strategist David Adams.

But higher borrowing costs would have an adverse effect on the economy, which is already contracting. Output fell 0.2% in the third quarter, and it will continue shrinking into the second half of 2023, according to economists in a Bloomberg survey.

“It makes you wonder whether rates in the UK can rise enough to compensate investors for such volatility without damaging growth,” Adams said.

The growth picture is inextricably linked with Brexit, which created more trade frictions with the EU, left the labor market short of workers and undermined business investment. That’s been compounded by soaring inflation, rapidly rising interest rates and a housing slowdown.

For Stephen Gallo, head of European FX strategy at BMO in London, the 2022 turmoil may have passed, but it’s far from all-clear for the pound.

“We had a chaotic, cathartic, crisis scenario where we hit a low, we bounced off the low and sterling is now in recovery, he said. “But there’s still a risk that structural economic and balance of payments weaknesses could cause stress and volatility.”

--With assistance from Vassilis Karamanis.

(Adds option market pricing in fourth paragraph.)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.