May 10, 2022

The Temperature Is the Least Surprising Part of the Texas Heat Wave

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Texas suffered extremely high temperatures in the last week, reaching 112° Fahrenheit (44.4° Celsius) in Rio Grande Village, near the Mexican border. Triple digit-readings were still rolling through the state's southern and mid-western band yesterday, even as the heat began to spread north through the Great Plains. Mexico faced even worse conditions, including 114°F in the northeastern city of Monclova.

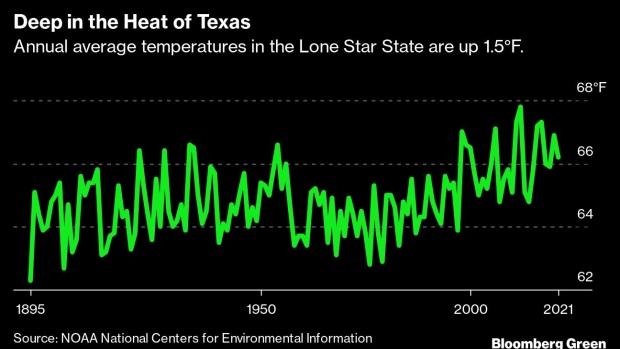

If there's one thing climate science is confident about, it's that today's unprecedented heat is tomorrow's normal. A Texas climate report released in October warned that the transformation of unprecedented temperatures into normal ones is a troubling but safe bet. Current heating rates in Texas "would make a typical year around 2036 warmer than all but the absolute warmest year experienced in Texas during 1895-2020," the authors concluded.

The least surprising thing about climate change in 2022 may be the heat. "This was predicted long ago," said Andrew Dessler, an atmospheric sciences professor at Texas A&M University. “It's the tip of the iceberg. We're going to see the impacts get a lot worse."

That's because, while it's already adapted for heat, Texas is climbing out of the temperature range that people are used to.

The race is on to transform infrastructure and industries to dramatically cut greenhouse gas pollution and help people adapt to warming that's already locked in. The flip side to surprise over triple-digit heat in early May is a lack of awareness over how fast technologies have come online to help. “We're undergoing an energy revolution right now,” Dessler said, “which most people don't realize. Wind and solar are our cheapest energy sources" in much of the world.

The following interview with Dessler, who made a high-profile appearance on the Joe Rogan Experience in February, has been edited for length and clarity.

What’s left to say about heat waves and climate change?

It's always useful to say, for the normal stuff, this was predicted long ago. It's the tip of the iceberg. We're going to see the impacts get a lot worse, very quickly, because we're getting out of a range, especially in Texas, where we're adapted to live.

What do you mean we’re exiting a range?

Here’s the way I like to think about climate impacts: People have this linear view, like every 10th of a degree of warming or every 100th of a degree will make things a little bit worse. And that's not how it works. What happens is, as the warming occurs, or as anything changes—rainfall gets more intense—you don't have any impacts. And then you pass a threshold and things suddenly get a lot worse very quickly. Take people working outside. As the temperature goes up, it doesn't have any impact on them. The temperature goes up a little more, it doesn't have any impact on them. The temperature goes up a little more, maybe they get uncomfortable. The temperature goes up a little bit more, they get heatstroke, and everybody stops working. So it's not this gradual thing. It's the thresholds. As the temperature warms, you're going to pass more and more of these thresholds. We already see it happening.

The thing that worries me is that, much like Covid, a lot of climate change is going to be this exercise in normalizing suffering, just like we do with 1,000 Covid deaths a day. It's the rich world that's put most of the carbon in the atmosphere. It’s useful to understand what we're doing, to make sure people don't start accepting these bad things that are going to happen as “Well, we don't have any choice,” because we do have a choice. The key issue around the world is how adaptive capacities really vary. The thing that would crater a really poor country is really not going to have as big an effect on Texas. We have the resources to take care of most things. Warming predictions or a global average warming predictions, for the rich world, climate change was kind of a bet. But for the poor world there was never any outcome that they would be okay. That essentially goes back to your capacity to adapt.

Is basic climate science as useful as it once was? The alarm bells are clear outside the scientific journals.

Further improvement isn't going to change the debate. I’m not saying it's not interesting, and there are people still working on that. I've actually changed my research into looking at impacts and the social-climate interface. We need to really focus on the things that matter, and a lot of that is, how do we get ourselves out of this problem? Because we understand the problem at this point.

And how do we get ourselves out?

We stop emitting as much greenhouse gas into the atmosphere. We know how to do that. We're undergoing an energy revolution right now, which most people don't realize. And then we need to adapt to the climate change we can't avoid. We need to do that in a way that's smart. You look at the Lake Mead and Lake Powell drying up. You just think, Holy hell, who's moving to Arizona? I actually think actually the cities in Arizona can do okay, because you can live on very little water in a city. But a lot of activities, like the farming, is doomed unless they spent a lot of money to bring water in from somewhere else. But it’s going to be expensive. Then lastly, we need to think about pulling carbon out of the atmosphere. It seems really hard to believe we're not going to need to do that. So we should be working on it now.

What’s struck you most recently about how Americans talk about climate change?

I don't think people understand that we really are in the midst of an energy revolution. I said, on some days Texas gets half its power from wind, and I get these emails: “That's bullsh--!” Let's look at the data. On these six days, they got over 50%, and that's just going to keep getting bigger. You'll tell people, here's the cost of solar and wind, and they don't believe you. People's understanding of energy, I think, lags reality by many years. Most people think that solar and wind are expensive, and they were 10 years ago. But they're not now, and people don't understand all the work that's been done on how you build a grid that runs on wind and solar and still produces power reliably.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.