Feb 10, 2022

U.S. inflation charges higher with larger-than-forecast gain

, Bloomberg News

U.S. inflation soars to 7.5% in January

U.S. consumer prices surged in January by more than expected, sending the annual inflation rate to a fresh four-decade high and adding more urgency to the Federal Reserve’s plans to start raising interest rates.

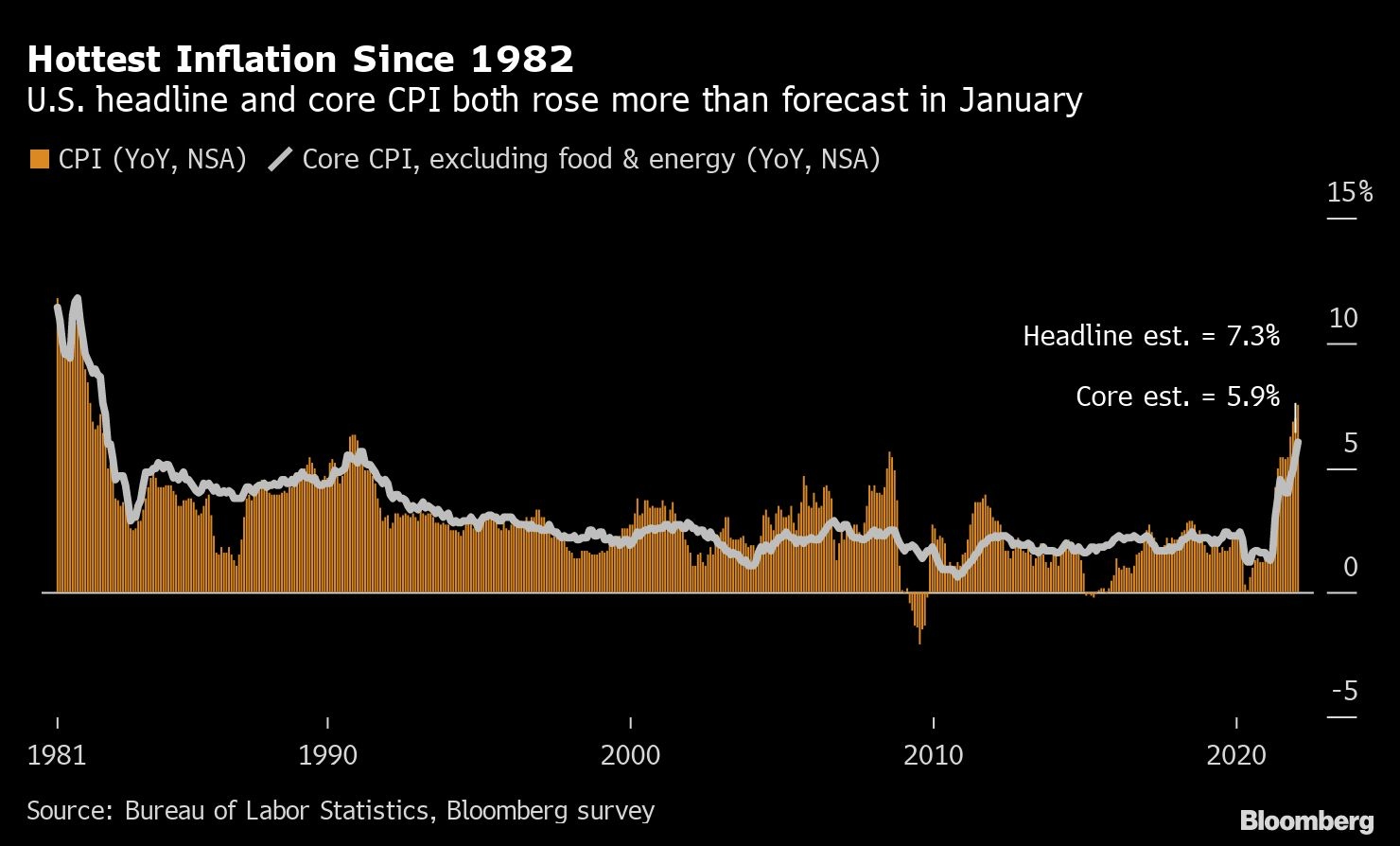

The consumer price index climbed 7.5 per cent from a year earlier following a 7 per cent annual gain in December, according to Labor Department data released Thursday. The widely followed inflation gauge rose 0.6 per cent in January from a month earlier, reflecting broad increases that included higher food, electricity and housing costs.

Excluding the volatile food and energy components, so-called core prices increased 6 per cent from a year ago, also the most since 1982, and 0.6 per cent from a month earlier.

U.S. Treasury yields are higher, while the dollar and S&P 500 are weaker. The median forecasts in a Bloomberg survey of economists called for a 7.3 per cent year-over-year increase in the CPI and 0.4 per cent gain from a month earlier. Economists have underestimated the monthly change in the CPI in eight of the last 10 months.

The data reinforce the Fed’s intentions to begin raising rates next month to combat broad-based inflationary pressures and could lead markets to expect even more aggressive action from the central bank. The steady run-up in prices has eroded recent wage gains and diminished American families’ purchasing power, sucking much of the air out of what has been an exceptional bounceback in the U.S. economy.

Leading up to the Fed’s March 15-16 meeting, policy makers will also have the February CPI and employment reports in hand.

Investors boosted their expectations for a a half-point increase in the federal funds target rate in March following the report. While most economists expect a more gradual approach to liftoff -- as has been telegraphed by several Fed officials -- the acceleration of inflation on the heels of rapid wage gains will keep the possibility of a half-point hike on the table.

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“January’s upside CPI surprise adds strongly to the case for a 50-basis point hike at the March FOMC meeting. The increase was broad-based, with energy, food prices and rents keeping prices elevated, and with some alarming increases in categories not seen before such as medical services -- which has a much larger weight in the PCE deflator, the Fed’s preferred price gauge.”

-- Anna Wong and Andrew Husby, economists

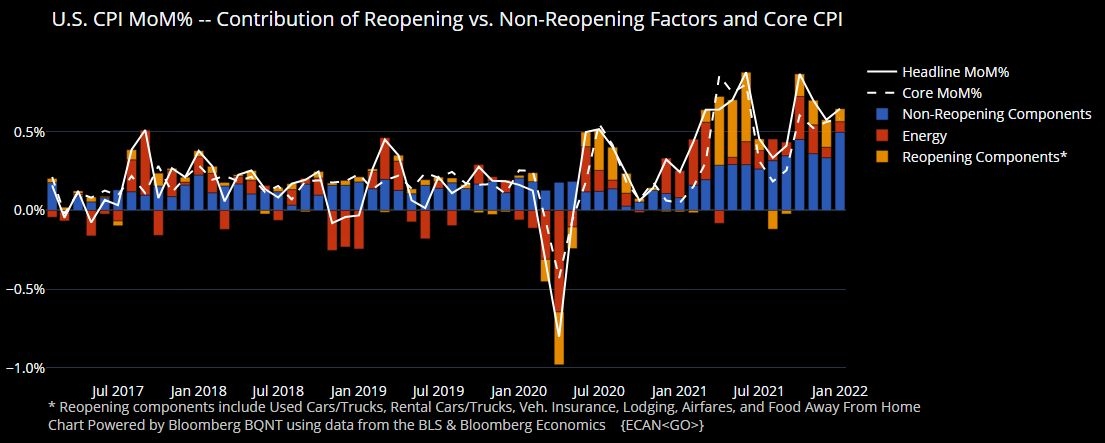

The rapid pickup in inflation boils down in large part to the mismatch between supply and demand. With the help of massive government stimulus, a surge in household purchases strained factories and global supply chains. Capacity constraints of U.S. producers trying to ramp up production were made worse by a smaller pool of available labor.

The tight labor market, in which the unemployment rate is now 4 per cent, has led employers to bid up wages in an attempt to fill millions of job openings and retain workers. Last year, compensation costs surged by the most in two decades.

Even so, wages aren’t keeping up with inflation. Inflation-adjusted average hourly earnings fell 1.7 per cent in January from a year earlier, marking the 10th straight decline, separate data showed Thursday.

Shelter costs -- which are considered to be a more structural component of the CPI and make up about a third of the overall index -- climbed 0.3 per cent from the prior month. The increase reflected the biggest jump in rent of primary residence since May 2001. Owners’ equivalent rent also rose.

Lodging away from home fell 3.9 per cent, the weakest print since April 2020 and likely reflecting reduced travel amid the surge in COVID-19 infections.

STICKY INFLATION

Housing prices are expected to offer a tailwind to inflation in coming months. Like wage increases, shelter is often considered a “sticky” component of inflation, meaning once prices rise, they’re less likely to come back down. A sustained acceleration in structural categories like shelter, rather than surges in volatile CPI components such as energy, presents a more serious threat to the central bank’s inflation target.

The report showed few signs that prices of merchandise are coming off the boil, while services costs are accelerating. On a year-over-year basis, goods inflation soared by 12.3 per cent in January, the biggest gain since 1980, while services costs jumped 4.6 per cent, the most in 31 years.

For President Joe Biden, the decades-high inflation presents a risk to his party’s razor-thin congressional margins ahead of the midterm elections later this year. With many pointing to the White House’s stimulus bill last year as a key driver of the price increases, Biden’s approval ratings have taken a hit as Americans face higher prices at the gas pump and the grocery store.

Food prices rose 0.9 per cent in January, the most in three months, and energy costs also advanced 0.9 per cent on gains in fuel oil and electricity. Residential electricity costs increased last month by the most in 16 years. From a year ago, food inflation is up 7 per cent, the most since 1981.

The broad increase in the CPI also reflected higher prices for household furnishings, used vehicles, apparel and medical care. Prices of household furnishings and health insurance both rose by the most on record on a month-to-month basis.

The report will likely further diminish the chances Biden’s Build Back Better plan will pass. Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia, who has repeatedly stalled the legislation, has frequently cited inflation as a reason to slim down the package.

The latest CPI figures also reflect an update to the relative importance of certain categories in the consumer basket. The new weights, which are based on spending habits in 2019 and 2020, include changes like a bigger weighting for used cars and trucks -- a reflection of how the pandemic changed consumption patterns in the U.S.

“This is a goods-dominated inflation backdrop,” said Tom Porcelli, chief U.S. economist at RBC Capital Markets LLC, who noted that merchandise now has a larger weighting in the CPI. “If the transition from goods to services spending is slower to evolve this year, you could continue to see some additional upward pressure on inflation.”