Jun 13, 2021

Worst Fears of Enduring Pain for Euro-Area Workers Are Subsiding

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- European fears that the pandemic will lead to a legacy of disfigurement across the labor market are starting to seem like more of a bad dream than reality.

With the region emerging from an unprecedented economic crisis that’s taken a particular toll on the young, economists from Credit Suisse Group AG to TS Lombard are becoming more confident that permanent damage to employment -- so-called scarring -- will be less severe than after the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

In November, European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde openly warned of the risk of persistent labor-market impairment, and she said on Thursday that “we are still concerned.” However, her chief economist, Philip Lane, said last month that there are reasons to be optimistic that scarring won’t be as bad as it was in the aftermath of 2008.

If his view crystallizes, that would chime with evidence from Australia to the U.S., which are further ahead on unlocking activity. It would be a welcome break for a region bedeviled by high structural joblessness, whose labor market began the crisis in a worse shape than in other major economies.

“We are going to be starting this recovery with a much lower level of unemployment that we usually have after a recession,” said Neville Hill, economist at Credit Suisse. “The amount of scarring that would impair a recovery is not really there.”

The ECB, OECD and European Commission have all upgraded growth forecasts for the economy, and improving data, from consumer sentiment to firms’ employment outlook and investment, also suggest wounds inflicted by lockdowns are less grave than they could have been.

A much-feared crisis spillover into the banking sector hasn’t materialized, and the bloc’s unemployment rate is at 8%, well below the more than 12% forecast by the OECD last June for a double-wave scenario. Buttressing the outlook is the prospect of hundreds of billions of euros in excess savings waiting to be spent.

There’s mixed evidence of a sustained hiring boom in the U.S., but the return of Wall Street workers to their office desks is signaling a resumption of pre-crisis activity. Meanwhile in nearly Covid-19-free Australia, much pandemic-induced unemployment have been recouped.

“I’m a bit more worried about scarring in Europe than I am in the U.S.,” said Dario Perkins, an economist at TS Lombard in London. Still, “there will be much less scarring from this crisis than there was after 2008. That’s pretty certain, as long as we’ve got the vaccines.”

For Lane, the key difference is that this crisis simply won’t last as long. “Scarring can be limited because the recession will be shorter,” he told Le Monde, adding that there are still “sources of concern.”

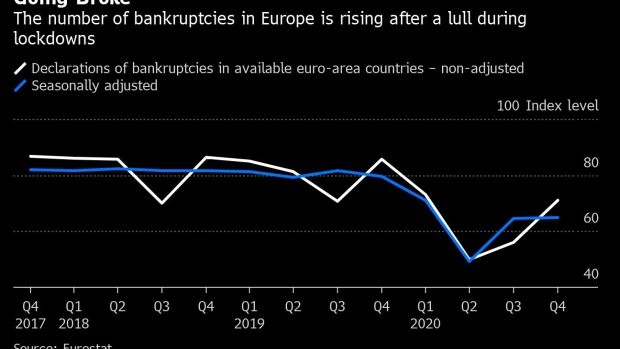

Some businesses will still go under, even though worries about a wave of insolvencies may be overblown, according to Bank of France Governor Francois Villeroy de Galhau.

Airlines and hotels will surely lag others in recovering, and trends like working from home might permanently depress demand for certain goods and services.

The impact of losses there could still be relatively contained in the wider labor market, according to Carsten Brzeski, an economist at ING Diba AG. Leisure and hospitality businesses are typically “very small,” he said. “So the effect on unemployment won’t be as big as in other crises.”

Even some larger firms are sanguine. While Deutsche Lufthansa AG expects to offer only 40% of its pre-pandemic capacity for 2021, Executive Officer Carsten Spohr insisted in late April that “small and medium companies, who will need that positive experience of corporate travel to see their customers, to see their suppliers, are making up a bigger share of our corporate customers than people think.”

Some things will surely change forever, perhaps with the de-urbanization seen in London entrenching itself elsewhere, for example. Joblessness could rise again as people rejoin the labor market, and prolonged inactivity might lessen their employability. Social distancing restrictions may endure, and there could be another flare-up of the virus.

Months of school closures will have a long-term effect, and young people might see weaker earnings later in life due to their ill-fated start into the world of work.

Whether the case for optimism can endure may depend on fiscal support, a message the ECB has been keen to drive home. On Thursday, Lagarde repeated a call to governments not to withdraw aid too soon, or risk “amplifying the longer-term scarring effects.” She also underscored the role of the European Union’s recovery fund in cushioning the blow.

“At some point support will be withdrawn -- that might create some shocks and uncertainty, particularly to some households,” said Aline Schuiling, economist at ABN Amro. “We all hope that when everything reopens they can just go back to work as if nothing happened. But this will probably not happen.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.