Jan 12, 2023

2022 Was One of the Five Hottest Years on Record, Scientists Find

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- In 2022, enormous rivers critical to trade dried up temporarily in Europe, the US and China. A third of Pakistan was inundated by monsoon rain. Ocean temperatures set a new record. Twenty-eight countries weathered their hottest years. An estimated 850 million people lived through their hottest-ever local average temperatures.

Last year was the fifth or sixth hottest year in records dating back as far as the mid-19th century, according to new temperature data released Thursday by NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, the US National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, the UK’s Met Office, the nonprofit Berkeley Earth and the Japanese Meteorological Agency.

“We are entering a realm where more and more of these weather extremes will be ‘unprecedented,’” said Joeri Rogelj, professor of climate science and policy at Imperial College London. “This doesn’t bode well for climate damages and resulting suffering.”

Updates to annual temperature records every January have become a reliable moment for the world to pause and consider the inexorable onset of global heating:

- The last eight years rank as the the hottest eight on record — or the last nine do, in the record maintained by NASA GISS. Copernicus, the EU’s climate science agency, reached a similar conclusion earlier this week.

- Of the 23 years that have passed in this century, 22 were the hottest ever (1998 beat out 2000), according to NOAA.

- There’s only a negligible difference between the fourth to eighth hottest years.

- Each decade has been hotter than the last since the 1960s.

“After decades of steady increasing warming, it’s indeed a challenge to say anything new,” Rogelj said.

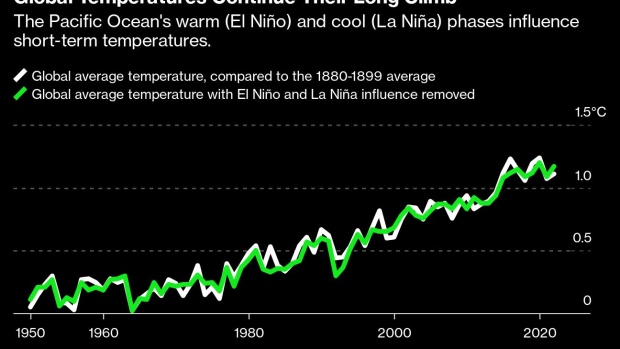

The Earth will continue to trap more and more heat as long as greenhouse gas pollution continues. But the gradual increase doesn’t necessarily explain the differences in year-to-year temperatures. It’s variations in weather, steered most powerfully by an oscillation in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, that have an outsize short-term influence on weather.

In El Niño years, warmth entering the atmosphere can boost the global heating — and often help set a new annual heat record. In La Niña years, such as 2021 and 2022, cooler water can dampen global average temperatures.

But there is an increasingly clear limit to just how much La Niña conditions suppress rising heat. The years 2018, 2021 and 2022 all saw La Niñas — and despite that each of them was nonetheless hotter than every hot El Niño year that occurred before 2016, according to NASA GISS.

For a clearer view of the warming itself, researchers are able to remove the El Niño/La Niña influence, minimizing year-to-year weather differences. With this variability stripped out, 2022 is the second hottest year, after 2020.

If you draw a straight line through a chart of global average temperatures since 1970, “2022 is pretty much dead on the trend,” said Zeke Hausfather, research scientist at Berkeley Earth. “So even though it’s a little cooler than some of the last few years, it’s right around where we’d expect global temperatures to be, given the underlying rate of warming of about 0.2C per decade.”

However predictable the temperature record has become, many scientists in recent years have been surprised by the pace of extreme weather events.

Every new year means a new line for the “warming stripes,” a visualization of the temperature record that represents each year as a color-coded vertical bar. Ed Hawkins, a professor of climate science at the University of Reading, came up with the graphic and said 2022 almost qualified for the darkest red category — remarkable for a La Niña year.

“The data from 2022 is stark, however you look at it,” he said. “Whether you view the figures in their raw form, or look at the data as another red line added to the climate stripes, the message is clear. Excess heat is building up across the planet at a rate unprecedented in the history of humanity.”

“It doesn’t stop. People are realizing it doesn’t stop,” said Katharine Hayhoe, chief scientist at The Nature Conservancy. “There is no lull in the headlines, where there’s no extreme weather and climate disaster around the world.”

The good news, Hayhoe said, is that over the past year she has “seen an exponential — and I really do mean that, an exponential — growth in reporting on what is actually happening to tackle the climate crisis. And that makes me so happy.”

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.