May 4, 2021

As Interest Rates Surge, Brazil Corporate Bond Market Reawakens

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Brazil’s local market for corporate debt is back in expansion mode after last year’s wipeout.

It looks to be a return to the glory days of a few years ago, when credit funds had been among the fastest-growing investments as Brazilian savers moved away from government bonds in search of higher payouts on floating-rate notes from companies. All that was derailed last year as the coronavirus set in and holders rushed for the exits. So far in 2021, sales are up 70% from the same span of 2020, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, with investors piling in amid forecasts for higher interest rates in the months ahead.

The revival is still in its early stages, with just three months of fund inflows since the turnaround began, but it’s paved the way for a boom in funding for infrastructure projects. After last year’s withdrawals prompted some money managers to shutter their corporate bond funds, the sector is once again vacuuming up cash amid signs the economy is emerging from the worst of its pandemic malaise.

“There is no selling pressure anymore since the biggest sellers, the more fragile credit funds, simply disappeared,” said Alexandre Muller, a partner and portfolio manager in Rio de Janerio at JPG Gestao de Recursos, which has 29 billion reais ($5.4 billion) in assets under management. “There was a cleansing effect.”

Brazil’s rebound is coming after a painful 2020. While credit markets around the world suffered steep losses as the pandemic set in, they roared back in the third and fourth quarters in most of the developed world. Not so in Brazil, where local bond issuance dropped 41% for the year and investors pulled money from credit funds for 11 straight months.

Prices tumbled with only a few banks as buyers, burning savers who had only recently grown comfortable with the idea of holding investments riskier than government bonds. The amount of money in credit funds had surged to a peak of 100 billion reais in June 2019, from 15 billion reais in 2014, according to JGP, which measures the holdings of independent firms.

One of the reasons for the growing popularity was that about half the funds allowed investors to withdraw their money with almost no notice. That turned the funds into a hard-to-resist source of immediate cash for holders grappling with fallout from the coronavirus crisis.

Credit funds posted record outflows of 9.6 billion reais in March 2020 followed by 4.1 billion in April, according to JGP. Withdrawals only stopped this February, by which time holdings had shriveled to 60 billion reais.

“The Brazilian bond market is going back to normality,” said Rogerio Monori, the Sao Paulo-based corporate and investment banking director at Banco BV.

Of course the market is still smaller than it was at its peak, and remains tiny relative to the amount of local government debt outstanding, which stood at 5 trillion reais in March. There’s also a risk that the relentless pandemic tearing through the country has the potential to undercut the revival in the corporate market.

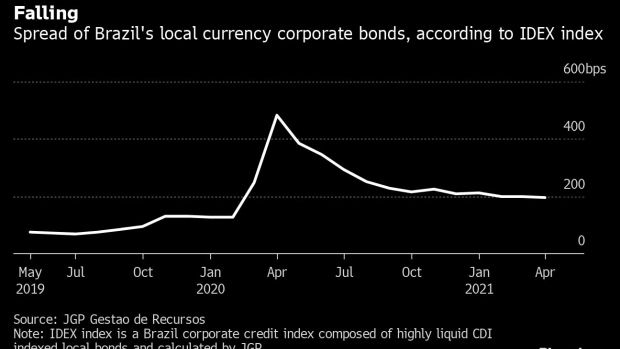

For now, though, Brazil’s interest rates have found a sweet spot for encouraging debt issuance. Average yield spreads over the benchmark rate have fallen to 2 percentage points after reaching as high as 5 points last year, according to an index calculated by JGP. That’s an attractive rate for borrowers.

Apparel retailer Lojas Renner SA in March sold bonds due in 2025 paying a 160 basis points spread, down from a 300 basis point premium it paid in May last year for slightly shorter notes. Utility company Aegea Saneamento e Participacoes SA sold notes due in 2027 in April at a 215 basis point spread, compared with a 300 basis point premium on shorter-term notes it sold in September.

While the spread has shrunk, the underlying benchmark rate looks likely to increase in coming months, boosting the appeal of corporate debt relative to equities or other riskier investments. The central bank raised the overnight rate by 75 basis points to 2.75% in March, and indicated another increase of the same size in May. Traders are already pricing in additional 250 basis points in increases later this year, which would take the key rate to 6%.

“The spreads are still good to investors in relation to the credit risk from the companies,” said Laurence Mello, a credit fund manager at AZ Quest Investimentos, which has 17 billion reais under management.

Companies are also finding it easier to sell longer-term debt, with maturities of up to 10 years for inflation-linked bonds and six years for those tied to the overnight rate, according to Felipe Wilberg, the fixed income and structured product managing director at Banco Itau BBA, the biggest underwriter of local corporate bonds this year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Most Brazil companies issued debt last year to buy smaller rivals, Wilberg said. This year, operators of airports, railways and roads are becoming a bigger part of the mix, taking advantage of new concessions auctioned by the government and favorable tax treatment for bonds that are tied to infrastructure.

As the market continues to normalize, more companies are expected to issue local bonds. Waterworks that serve the state of Rio de Janeiro were privatized last week and will need 22.7 billion reais of investments, some of which could come from local capital markets.

More issuance would be good news for investors who are siting on high levels of cash and looking for opportunities to put their money to work.“We are very excited about this asset class,” said Artur Nehmi, a Sao Paulo-based fixed income manager at Fundos de Investimento, which has 3 billion reais under management. “Prices are still good.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.