Oct 23, 2019

Boeing Stirs Fears of Cash Crunch With Tab for 737 Max at $9 Billion and Rising

, Bloomberg News

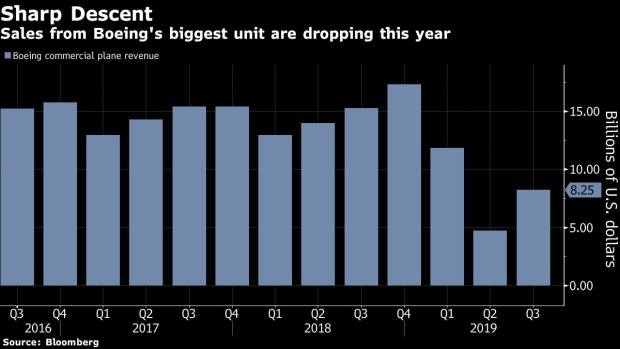

(Bloomberg) -- Boeing Co.’s $9.2 billion tab for the grounded 737 Max is combining with sales pressures on two wide-body models to put the planemaker in cash-conservation mode.

The cash drain will peak next year when the jet is flying again and production starts to shift into a higher gear, Boeing Chief Financial Officer Greg Smith said Wednesday. That will coincide with a factory slowdown for the 787 Dreamliner and the 777, eroding revenue from the company’s top two long-distance models.

The evolution of the company’s business strategy will depend largely on the financial fallout from the best-selling Max. But stabilizing 737 production and reducing debt will be the priorities, outweighing Wall Street goodies such as share buybacks or any spending on developing new jetliners.

“Look, considering the circumstances of where we are, obviously that cash profile is more challenging than it was,” Smith said on Boeing’s quarterly earnings call.

Boeing consumed $2.9 billion in free cash during the third quarter as it continued to churn out narrow-body Max jets, which the company can’t deliver because of a global flying ban imposed in March after two fatal crashes that killed 346 people. That’s the most the company has burned through in at least a quarter-century, and a $7 billion swing from $4.1 billion in cash generation a year earlier.

Wide-Body Setbacks

With the Max crisis still at full boil, Boeing revealed new setbacks for its wide-body aircraft. The manufacturer plans to pare output of the Dreamliner to 12 jets a month by late next year from 14 now amid an order drought stoked by trade tensions with China.

The debut of the 777X has shifted to early 2021 from late next year as Boeing awaits delayed engines. In the interim, the manufacturer is paring production of its current 777 models.

“The cash capability of this firm is somewhat reduced from what we thought in February” before the worldwide Max grounding, said Bloomberg Intelligence analyst George Ferguson. Over the longer term, Boeing will need to spend more on research and development, capital investment and airplane development “than we would’ve perceived before the Max had these problems.”

Boeing is trying to work through one of the biggest crises in its 103-year history in the wake of the crashes. The Chicago-based manufacturer, which is under investigation by the U.S. Justice Department and Congress, ousted its commercial-airplanes chief on Tuesday and stripped Chief Executive Officer Dennis Muilenburg of his role as chairman on Oct. 11.

The planemaker is optimistic U.S. regulators will certify the revamped 737 as airworthy this quarter, and teams of Boeing workers are ready to swarm airline customers and the company’s own storage lots to prepare hundreds of parked planes for flight. Production of the Max will increase 36% to 57 jets a month by late next year, the company said.

The shares advanced 1% to $340.50 in New York, as investors breathed a sigh of relief that the news wasn’t worse. Boeing has dropped 19% since the second crash, the biggest decline on the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

“The lack of incremental bad news on the Max has got people excited,” said Ken Herbert, an analyst with Canaccord Genuity. While investors remain “healthily skeptical” that Boeing can gain U.S. approval for the Max to fly this year, “if they get the FAA to sign off on it, then that shifts the whole discussion between airlines and other regulators.”

Adjusted earnings fell to $1.45 a share in the third quarter, compared with the $2.17 average of analyst estimates compiled by Bloomberg. Sales tumbled 21% to $20 billion from a year earlier. That was slightly ahead of analysts’ expectation for $19.7 billion.

Boeing is in the process of delivering to the Federal Aviation Administration the final items needed to certify the revamped 737 Max software, Muilenburg said. The U.S. regulator is involved as the final software is tested in the company’s labs. Boeing has also submitted the “final system description document of the changes to the Max” to the FAA, an important milestone, he said.

While Boeing didn’t report another big accounting charge for its Max woes, as some analysts had predicted, the company recorded another $900 million in estimated production costs for the 737 due to the grounding. That pushed the total bill beyond $9 billion. Boeing has reported $3.6 billion in rising costs to build and deliver the Max planes it has already sold, which will clip future profit margins.

Once the plane returns to the skies, Boeing plans to deliver most of the parked planes within a year, helping to refill the company’s coffers. For now, though, the cash drain will continue as long as the Max is barred from commercial flight. Southwest Airlines Co., United Airlines Holdings Inc. and American Airlines Group Inc. don’t expect to carry passengers on the plane until next year.

“We’re going to breathe a super sigh of relief when the airplane is in the air,” Ferguson said of analysts’ response to the Max’s eventual commercial comeback. “And then we’re all going to go back to our models and wonder, ‘What does this mean.’”

--With assistance from Molly Smith, Richard Clough and Brad Skillman.

To contact the reporter on this story: Julie Johnsson in Chicago at jjohnsson@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Case at bcase4@bloomberg.net, Susan Warren

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.