Mar 3, 2022

China’s Energy Sector Methane Emissions Dwarf U.S. and Russia

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- China’s coal operations spewed so much methane last year that it had the same global warming impact as all the carbon dioxide emissions from international shipping. The nation’s energy sector, the world’s largest coal producer, accounted for roughly a fifth of total global methane emissions from oil, gas, coal and biomass. It generated over 50% more than the next largest emitters: Russia and the U.S. The estimates, which are the latest from the International Energy Agency’s Methane Tracker, show the enormity of China’s task in mitigating its methane pollution. “China has encouraged miners to utilize more methane produced during the mining process but there remain major obstacles,” said Nannan Kou, an analyst with BloombergNEF in Beijing. “Capturing the gas requires a lot of capital investment and most mines aren’t near major gas transmission pipelines.” Different entities are often responsible for extracting coal and any methane produced, making efforts to curb emissions more complicated, he added.

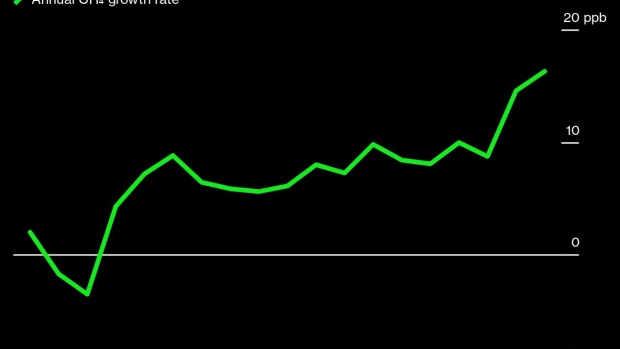

China’s National Energy Administration and its Ministry of Ecology and Environment didn’t answer questions sent by fax seeking comment. The report, released last week, also highlighted the gap between methane releases detected by satellite and emissions reported by nations to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.Many countries compile that data by essentially adding up numbers on an excel sheet. A nation might look at its energy system and, for example, count the total number of compressor stations, then multiply that by generic methane release rates for the amount of fuel processed through them. But that approach can fail to reflect the scale of methane emissions observed by satellite and aerial surveys.“In many cases countries don’t base their inventories on measured data,” said Christophe McGlade, head of the energy supply unit at the International Energy Agency. “As more and more measurement campaigns are being carried out we are seeing that there is this growing discrepancy.’’The IEA said global methane emissions from the energy sector exceeded the sum of nationally reported inventories by about 70%. Atmospheric methane increased by a record amount last year, to 1,876 parts per billion, according to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, helping push global temperatures in 2021 to the fifth-highest ever recorded.

Satellite observations of giant methane leaks are starting to push authorities to update emissions reporting requirements to include more accurate measuring technologies, according to McGlade. One of the major insights from satellite data is that super-emission events can make a big difference to total national inventories.Although these events can be infrequent and sometimes only last a few hours, oil and gas ultra-emitters account for as much as 12% of global methane emissions from the sector, according to a study published in Science last month. The French and American scientists who authored the study used satellite observations to identify more than 1,800 major releases of the gas, some of which spread for hundreds of kilometers. Another factor that has driven the widening divide between satellite-detected and reported emissions is that inventories submitted by many countries, including major fossil fuel producers like Iraq and Nigeria, haven’t been updated in years. The UNFCCC didn’t respond to an emailed request for comment.Global energy producers spewed 135 million metric tons of methane last year, a 5% increase from 2020, according to the IEA’s annual assessment, which included country-level estimates for emissions from coal for the first time. That was higher than the global increase in carbon dioxide emissions, which rose 4.3% in 2021.

Much existing research has focused on cutting methane emissions from oil and gas because it’s viewed as the easiest and cheapest solution. Methane from coal has escaped some of that same scrutiny because production of the fossil fuel needs to be drastically reduced to meet climate goals anyway.

But taking into account methane from coal paints a dramatically different picture of global emissions. It caused China to become the No. 1 emitter in the IEA’s latest update, from sixth place in its 2021 report, when emissions were estimated from oil and gas and didn’t include the dirtiest fossil fuel.

China has declined to join an international effort to curb methane led by the U.S. and EU, but has said it’s working on a plan to contain emissions. The country’s coal sector offers Beijing the biggest opportunity to cut its methane emissions, according to an analysis from the United Nations.

Methane can also escape into the atmosphere from landfills and agricultural activities. But those kinds of emissions are more difficult to control; we have the tools we need right now to stem releases from the energy sector. Almost all methane emissions from oil and gas can be avoided at no net cost because the extra gas can be captured and sold, according to the IEA, and there are “significant opportunities” to cut coal methane.

“Such a strong alignment of cost, reputational and environmental considerations should push the oil and gas sector to lead the way with methane emissions reductions,” the IEA said. The agency said oil and gas operators should stop setting targets to cut emissions only as a proportion of production, and instead “adopt a zero-tolerance approach.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.