Dec 11, 2023

China’s Surging Real Borrowing Costs to Drag on Growth Into 2024

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- China’s real borrowing costs are expected to stay high in 2024 as deflation pressures linger, posing yet another threat to growth in the world’s second-biggest economy.

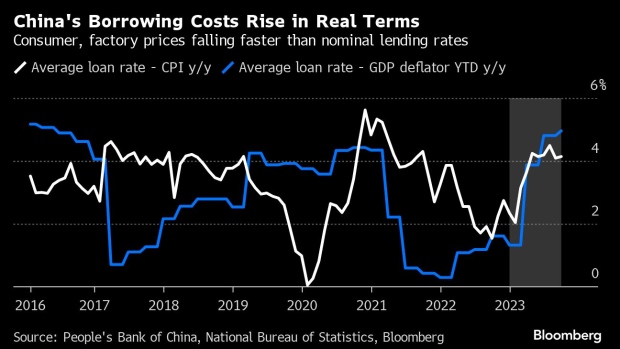

Calculations by Bloomberg News show those rates — adjusted for inflation and reflective of the actual cost of borrowing funds — have topped 4% and may even be near 5%, which would be the highest level since 2016. That’s because consumer and producer prices have fallen at a much faster pace than the country’s average loan rate, a figure largely based on changes in benchmark rates set by the People’s Bank of China and major lenders.

“China’s real interest rates are quite high, and are still rising,” said Larry Hu, head of China economics at Macquarie Group Ltd. Along with keeping company borrowing costs elevated, he added that the high rates mean “residents are more inclined to save.”

That bodes ill for the economy, considering weak business confidence and a population that’s more likely to save than spend have already been challenges this year. The benchmark prime rate on one-year loans is 3.45% — roughly 150 basis points lower than what real loan rates are actually estimated to be near.

The problem is there aren’t many signs that suggest real interest rates will see a reversal. China’s consumer price index in November recorded its steepest drop in three years. The nation’s widest measure of prices, the GDP deflator, was negative for two consecutive quarters this year for the first time since 2015.

Deflation is dangerous because it risks creating a downward spiral, with consumers holding off on buying anything on the expectation that prices will keep falling. Businesses uncertain about future demand may also lower production and investment. Several economists see pressures persisting into next year: Goldman Sachs Group Inc. economists forecast annual CPI will rise just 0.5% in 2024, while Nomura Holdings Inc. analysts see it increasing 0.6%. Some, including economists at Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd, see prices potentially declining.

What Bloomberg Economics Says ...

“Without strong catalysts to counter the property slump — a major driver of the deflationary downdraft — we see a 50% chance that CPI deflation will persist at least through the first half of 2024. Stronger policy support is needed to stimulate demand.”

— Eric Zhu, economist

Read the full report here.

On the policymaking side, authorities face several limitations to their ability to support the economy by making big interest rate cuts. Top leaders have already signaled they’ll be more cautious about monetary easing going forward, suggesting the size of any interest rate cuts in 2024 are likely to be quite small as the focus turns to fiscal stimulus as a means of economic support.

This year, the PBOC trimmed policy rates twice — a reflection of a restrained approach to stimulus in recent years as policymakers try to preserve their room for action and avoid building up debt within risky sectors, such as property. Cutting rates can also weigh on profit margins for banks, and those margins are already under pressure. The outlook for the yuan, meanwhile, remains uncertain as long as the Federal Reserve keeps rates high. The US central bank isn’t expected to start cutting rates until well into next year.

“Real interest rates are important, but obviously what the PBOC can do is rather limited,” said Wei He, China economist at Gavekal Dragonomics. “It’s impossible for the PBOC to match the changes in CPI for interest rates because that would mean substantial changes to rates, which is very much against its methodology.”

Gavekal’s He said the central bank may continue to make moderate cuts to policy rates into next year if the property sector worsens — though such trims would only amount to around 10-to-20 basis points. Any cut would require banks to also lower their deposit rates as they try to preserve their profitability.

There are other monetary policies that may be in play, too. Mo Ji of DBS Bank Ltd. flagged a possible 25-basis point reduction to the reserve requirement ratio for banks in the first quarter, which would free up more long-term cash in the economy. She also sees banks lowering their LPRs by 10 basis points later in 2024.

Eventual easing by the Fed would also likely open a bit more room for rate cuts, since a weaker dollar would mean less pressure on the yuan. Still, Macquarie’s Hu pointed to the need for policies — particularly on the fiscal side — that would help drive inflation up.

“Macroeconomic policies — not just monetary policy — should be more proactive,” he said. “Given the current circumstance, fiscal policy may be more important. But the end goal is the same, and that is reflation.”

--With assistance from Wenjin Lv.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.