Jan 29, 2019

Democrats, Republicans alike won't support USMCA with tariffs in place: Trade rep

The Canadian Press

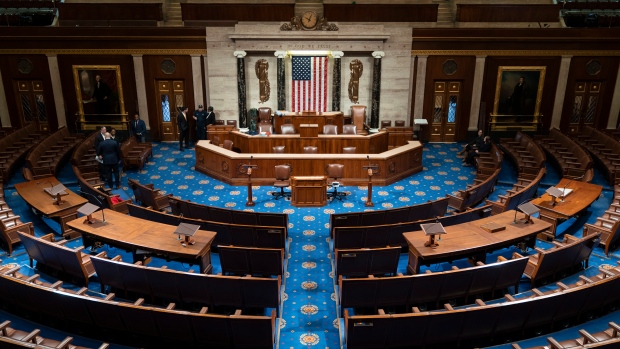

WASHINGTON -- A key member of Congress on the international trade file says Republicans and Democrats alike are telling him they won't back President Donald Trump's North American trade deal if punitive tariffs on steel and aluminum remain in place.

Rep. Kevin Brady, the ranking member of the House Ways and Means Committee, which has jurisdiction over international trade, says while support for the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement varies on Capitol Hill, there's a consensus the tariffs must go -- and must not be replaced by quotas.

"Key things in my discussions with members, Republicans and Democrats, is that they're not really willing to consider this agreement until the steel and aluminum tariffs are ensured to be lifted off, including quotas," Brady said Tuesday during a brief appearance at a trade conference in Washington.

"Frankly, quotas can be just as disruptive as tariffs can be ... the truth of the matter is the agreement's strong enough to stand without them. These are fair trading partners, trading fairly in those metals, so I think that's going to be one of those threshold issues."

It doesn't take long for a discussion about the agreement -- christened the USMCA by President Donald Trump, but known more colloquially as the "new NAFTA" or "NAFTA 2.0" -- to turn to one of two subjects: the future of the deal in Congress, and when and whether the tariffs, imposed under national security provisions, will disappear.

Brady said the process of "counting the noses" -- determining which members of Congress support the agreement, which don't, and why or why not -- is underway in order to produce an inventory of issues for U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer to address.

That list most prominently includes a concern among Democrats that the agreement lacks effective enforcement tools for its labour and environmental provisions. Republicans, Brady said, are concerned about the erosion of investor-state safeguards and a clause -- initially vehemently opposed by Canada -- that the deal be open to review every six years.

"Every trade agreement is a mixed issue, and I know Democrats are voicing the need for strong enforcement on the labour provisions," he said.

"For Republicans, it's more the architecture; the investor-state protections are not as broad and as strong as they need to be in our members' views, we still are trying to figure out how the sunset mechanism works for or against certainty for trade long term."

As a result, it's still too soon to predict when a vote might take place on Capitol Hill, especially given the lingering hangover of a month-long government shutdown, a bruising political battle over Trump's U.S.-Mexico wall and the threat just three weeks in the future of either a shutdown sequel or a declaration of a national emergency at the southern border.

And while conventional wisdom has long held that neither Canada nor Mexico would pass judgment on the agreement before the U.S., it might be worth rethinking that approach in order to spur action in Washington and discourage changes, said Miriam Sapiro, a Democrat who served as deputy and later acting U.S. trade representative under President Barack Obama.

"It's fair to say that this agreement is likely to pass more quickly than Mexico will pay for a border wall," Sapiro joked.

"I think it would help if Mexico and Canada could pass the agreement first, for two reasons: first of all, that puts more pressure on the Congress to consider it in a timely fashion, and, second of all, it actually makes it harder for anybody to speak seriously about reopening the text."

Sapiro, who was taking part in a USMCA panel alongside Canadian Chamber of Commerce president Perrin Beatty and Mexico's chief NAFTA negotiator, Kenneth Smith Ramos, said she also believes a little discord around a new trade agreement is not evidence of existential issues.

"There is a range of issues coming out and that is healthy," she said. "If you had one side very happy with it, then obviously the other side would be less so."

Count Beatty -- a former Mulroney-era cabinet minister who was in government for both the negotiation of the original Canada-U.S. free trade deal and later NAFTA -- among those who are less than thrilled with the final product, but cognizant of the possible alternatives.

"This is the first time that I can recall the Canadian government being part of negotiations, looking to negotiate something less than what we previously had," Beatty said.

"I don't see it as NAFTA 2.0, I see it more as NAFTA 0.8. I think what we need to do, and the way most Canadians see it, is we need to judge it not against our aspirations about what we wanted to see ... but we have to judge it against what the option was on the table. And the option was potentially a trade war between Canada and the U.S. and the loss of something we'd worked very hard to build."