Jul 20, 2022

ECB Aims for Bulletproof Crisis Tool Anticipating Legal Showdown

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

For European Central Bank officials devising a crisis tool that will be credible enough to keep the euro together, the biggest challenge may be to get it past the lawyers.

President Christine Lagarde and her colleagues know any measure they reveal on Thursday is likely to be scrutinized by Germany’s constitutional court. Every one of the ECB’s past bond-buying programs has provoked lawsuits, with each getting progressively more complicated to resolve.

Given that history, the Governing Council’s creation of a tool that can facilitate interest-rate increases while stemming subsequent market speculation on Italy’s public finances may involve more legal considerations than any monetary policy decision since the euro was founded.

The challenge is to ensure any plan conforms to the ECB’s mandate of delivering price stability and doesn’t directly finance governments. That means a decision, on when and under what circumstances it can buy bonds, needs to be matched by safeguards and conditions countries must fulfill in exchange.

“Managing spreads of individual member states is a minefield,” said Christoph Ohler, a law professor at the University of Jena in Germany.

To navigate the legal quagmire, Ohler reckons the ECB must conduct an analysis of what is proportionate, assessing the current situation and economic prospects for the next two years.

Officials should weigh costs and benefits of different measures, including negative effects such as moral hazard on national fiscal policies, he says. That would build the foundations for a defense in court.

The burden of determining if a measure can run that gauntlet will fall on the ECB’s chief legal official, Chiara Zilioli, a Harvard-educated former Fulbright scholar with a doctorate from the European University Institute in Florence. Lagarde’s own background as a lawyer may draw her attention to the detail too.

Court Opponents

Among potential plaintiffs they want to outwit is Markus Kerber, a Berlin finance professor who sued against previous measures and is preparing to fight this one. Unlimited ECB bond purchases of individual countries would oblige Germany to consider exiting the euro, he says.

Most legal challenges have failed until now, though cases against the central bank’s pandemic program are still pending.

Its closest shave was over quantitative easing. In a 2020 judgment, Germany’s top judges conditionally prohibited the Bundesbank from implementing ECB policies, in a ruling that legal scholars described as a “declaration of war” on the primacy of European Union law and led to a political standoff with the European Commission.

Germany’s central role points to the importance of getting Bundesbank President Joachim Nagel on board. That might avert the kind of confrontation that saw his predecessor Jens Weidmann and former ECB official Joerg Asmussen give opposing statements on a crisis program in court in 2013.

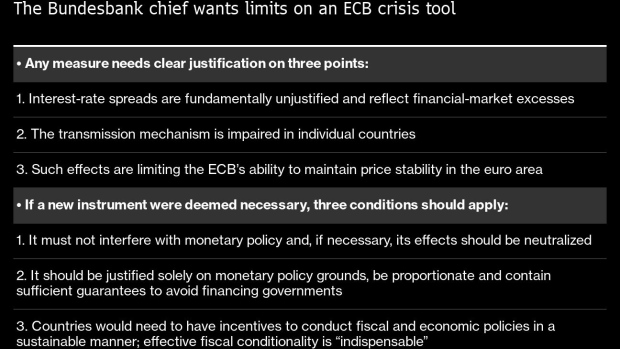

The Bundesbank chief insists any tool is for “exceptional circumstances and under narrowly defined conditions,” pointing to his need for anything to be legally watertight.

A safeguard to help that would be the involvement of the European Commission or the European Stability Mechanism in determining whether benefiting countries meet conditions set for them.

But that’s only one strand of the ECB’s struggle to square the circle of what’s lawful with what works. Officials are balancing the desire for seemingly unlimited firepower with a need for boundaries, and want to tame markets without blunting the discipline they exert.

Among arguments coloring the discussion, Greek Governor Yannis Stournaras says any program should be big enough, France’s Francois Villeroy de Galhau reckons the ECB should be able to sell bonds it buys before they mature, and colleagues from Lithuania and Latvia insist that it mustn’t add stimulus that counters rate hikes.

One strategy might be to take inspiration from the Outright Monetary Transactions program that followed then-President Mario Draghi’s pledge in 2012 to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro. It’s closest in character to what policy makers deem necessary and was judged by both German and EU courts to be legal.

“OMT is subject to clear conditions,” Nagel said on July 4. “This is important from a legal perspective.”

Whatever the ECB does, it may be helped by a generational change at Germany’s highest court, according to Alexander Thiele, a professor at the Berlin-based BSP Business and Law School.

A critical judge has already left the chamber responsible for cases involving Germany and the EU. Three more out of a total of eight will leave within the next 18 months.

“An era is coming to an end,” Thiele said.

Even so, it could take years of litigating before officials can be sure of being on a sound footing, said Armin Steinbach, a professor of law and economics at HEC in Paris, who previously worked at Germany’s finance ministry.

“Legal uncertainty will hang over the ECB like the sword of Damocles,” he said. “That risks reining in the ECB because policy makers can’t be absolutely sure they’re in the clear. It also threatens to undermine the tool’s full effectiveness if markets get the impression there are legal problems ahead.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.