May 4, 2023

ECB Bid to Diverge From Fed Pits Lagarde Against Tide of History

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The European Central Bank’s newfound status as the standard-bearer of monetary tightening sets up President Christine Lagarde for a tussle with investors doubting how long the euro zone can plow its own course.

Hours after the Federal Reserve’s hint on a possible halt to interest-rate hikes, she insisted the Frankfurt institution is in no mood to pause — a stance already being tested by traders betting no one can sustainably defy the gravitational pull of US policy.

Lagarde’s case to keep tightening and decouple from the direction of travel set in Washington is that inflation risks remain “significant,” and the ECB’s tightening cycle is less advanced.

Implicit there is the view that euro-region banks can avoid financial turbulence in the US that’s led to the downfall of Credit Suisse and even deposit outflows in the UK. America’s fiscal standoff, meanwhile, is another reason Europe may be able to set its own destiny for now.

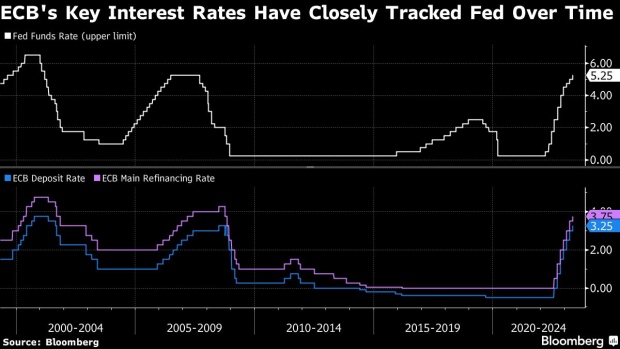

But past experience suggests any divergence won’t last: The ECB’s current tightening followed that of the Fed after inflation hit both the euro zone and the US. Even in 2008, Europe couldn’t stay immune to the global financial crisis bred on the other side of the Atlantic.

“In history there is no example of the ECB hiking rates in a sustained manner when the Fed stops, let alone cuts rates,” Frederik Ducrozet, head of macroeconomic research at Pictet Wealth Management told Bloomberg Television. “But this time is a bit different. So we do expect the ECB to continue to hike at least another meeting.”

For traders, who expect the Fed to cut rates by almost 90 basis points before 2023 is over, the end is in sight for the ECB. They pared bets on increases in the deposit rate since the quarter-point hike — pricing a peak of 3.66% by September, compared with 3.90% expected as recently as last week.

The yield on two-year German debt fell 16 basis points to 2.48% — the lowest in a month.

“Market pricing of future policy rate moves is almost certainly not what the policymakers expected,” said Théophile Legrand, a rates strategist at Natixis who recommends shorting two-year German bonds after Thursday’s “excessive” rally. “The market believes that monetary tightening is coming to an end, like the Fed.”

While some ECB officials favoring a bigger rate increase didn’t put up much of a fight, according to people familiar with the deliberations, the overall outcome still leaves the euro zone set for more hikes.

A faster wind-down of its balance sheet was even a “hawkish surprise,” according to ING rates strategist Antoine Bouvet.

“We know as of today that we have more ground to cover,” Lagarde said. “Whatever the decision of the Fed is in the next few weeks months, we are going to be riveted to our objective.”

Bank of France Governor Francois Villeroy de Galhau echoed that sentiment, telling Radio Classique on Friday that “we’ve done what we needed to do, even if there will probably also be further hikes.”

Emboldening the ECB is its collective view that prices aren’t yet fully under control. Lagarde cited recent wage agreements as adding to the risks, “especially if profit margins remain high.” Headline inflation even accelerated in April, reaching 7%.

It’s the extent of tightening in the US — 500 basis points compared with just 375 for the ECB — combined with jitters caused by regional bank failures that have left the Fed in a possible holding pattern.

By contrast, aside from a wobble for Deutsche Bank, Europe has weathered that turmoil well. While underlining that there’s no room for complacency, ECB Vice President Luis de Guindos reiterated that its banks are “resilient.”

Whether that remains the case will help determine how long ECB hawkishness can endure. Megan Greene, global chief economist at the Kroll Institute and a future Bank of England policymaker, said central banks will struggle to keep such pressures at bay.

While there’s no full-blown banking crisis now, “we can be sure that there will be more financial instability going forward as central banks are hiking rates or keeping rates high,” she told Bloomberg Television. “When you have financial instability, that impinges on the macro picture.”

That view would be ratified by the experience of the 2008 crisis, which appeared at first to pass much of Europe by, before the sovereign-debt mess ensued.

Even if financial stability can be preserved, it’s hard to find a market observer who reckons the ECB can enduringly decouple its policy course from the Fed’s.

“It was only a couple of years ago when clients were asking us whether the ECB would ever raise interest rates,” said Ulrich Leuchtmann, an FX strategist at Commerzbank. “Now they’ll be raising rates when the Fed isn’t — this is a very novel situation. I’m not certain the ECB will truly be more hawkish than the Fed in the longer term.”

--With assistance from Jeremy Diamond, Guy Johnson, Alix Steel, Jonathan Ferro, Jana Randow, Gaspard Sebag, Alexander Weber, Jasmina Kuzmanovic, Andrea Dudik and James Hirai.

(Updates with French central bank chief in 13th paragraph)

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.