Jan 26, 2023

EU Considers Capping Russian Diesel at $100 Ahead of Import Ban

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The European Union is floating a plan to cap the price of Russian diesel at $100 a barrel — a level that might help to stave off the very worst effects of a fuel-imports ban that the bloc will impose on Moscow in just 10 days’ time.

The EU’s executive arm is considering cap levels after the Group of Seven nations offered a price range based in part on the existing cap on Russian crude oil. The thresholds are expected to apply from Feb. 5, the same date as the EU will ban almost all imports of refined Russian products as punishment for the nation’s invasion of Ukraine.

The EU and G-7 want to impose the limits on Russian exports to third countries, whose companies would only be able to access key western services if they comply. The $100-a-barrel cap would apply to products like diesel that trade at a premium to crude, according to people familiar with the matter. A lower $45 threshold would be set for discounted ones like fuel oil, the people added. The figures could still change during talks between member states.

The negotiations need to balance two competing goals: limiting Russian revenue while preventing price spikes or shortages in key products on the global market. The EU will have to agree unanimously on price cap levels, which the G-7 will then need to approve.

EU diplomats will start discussing the prices levels more formally on Friday and heated talks are expected to continue over the next several days, with a group of countries seeking to impose stricter limits on Russian revenues from oil exports and toughen broader EU sanctions on Moscow.

What Europe Risks With Wider Sanctions on Russian Oil: QuickTake

European officials have been worried in particular about shortages of diesel after the imports ban, and the price cap is aimed at making sure Russian exports can still be sold to other parts of the world, thereby keeping global supplies in balance.

There’s still uncertainty about whether other regions will fill the buying void when Europe’s ban starts, but caps that are acceptable to Russia should help to keep trade flowing.

“We would expect Russian crude runs to be largely unaffected by this,” said Alan Gelder, vice president for refining, chemicals and oil markets at Wood Mackenzie Ltd. “Flows will largely continue and it will reduce Russia’s revenue.”

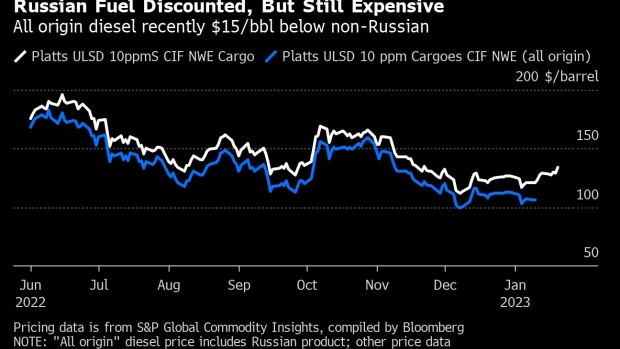

To put the $100-a-barrel cap in context, headline diesel futures are currently trading at about $130 a barrel in northwest Europe, according to ICE Futures Europe data.

Russian supplies have, however, recently been trading at a large discount to those from elsewhere, meaning that the impact on Russian sellers’ revenues may not be so large, data provided by S&P Global Commodity Insights show.

The firm, better known by oil traders as Platts, along with competitor Argus Media Ltd., stopped certain Russian diesel assessments earlier this month in preparation for the EU’s seaborne imports ban. On Jan. 10, Platts assessed Russian diesel at a discount of $113.50 a ton, or $15.20 a barrel, to non-Russian supply.

The price cap mechanism works by allowing European companies to provide financing, insurance and other important services for oil exports from Russia — but only for purchases at or below the threshold.

Trade Uncertainty

While the cap may not be too impactful, the EU’s imports ban could be. The measures will deprive Russia of its top diesel export market and the bloc of its main external supplier.

As such, the cap is secondary to the imports ban, said Richard Bronze, head of geopolitics at consulting firm Energy Aspects Ltd.

“The looser the price cap, or the higher the price cap is set for diesel, it makes it slightly easier for Russia to redirect some of the exports that will no longer be going to Europe,” he said. “But even a very high price cap wouldn’t mean that Russia could find alternative destinations for all of those supplies, and I don’t think the $100 a barrel is anywhere close to what I’d classify as a very high price cap.”

Latin America

G-7 officials expect that Russian diesel currently sold to Europe will likely find buyers in Latin America and Africa. Europe, meanwhile, will try to buy diesel from the Middle East and the US, which currently sell more to Latin America and Africa.

The changes could usher in higher shipping costs since some shipments will be going over a longer distance.

The refined fuels cap comes after the EU agreed late last year to set an upper limit on Russian crude exports at $60 a barrel, which was the end result of a lengthy negotiation.

That system has helped keep Russian oil on the market, but at a discount. Russia’s Urals grade crude, its top export stream, was $45.55 a barrel at the Baltic Sea port of Primorsk last week, according to data provided by Argus Media. The main Brent crude contract was at about $85 at the time.

US, Allies Agree to Review Russian Crude Price Cap in March

(Updates with analyst comment from 14th paragraph.)

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.