Sep 21, 2022

Europe’s Subzero Rate Era Poised to End as SNB Plays Catchup

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The Swiss National Bank will probably end Europe’s decade-long experiment with negative interest rate policy this week as officials emphatically hike above zero.

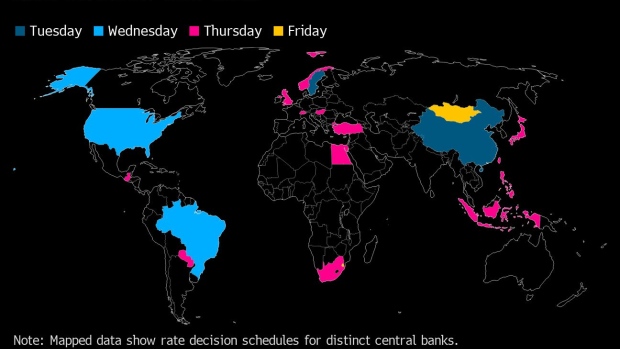

Economists are split three ways on what to expect on Thursday, with about half surveyed anticipating a 75 basis-point increase -- matching European Central Bank action this month -- to 0.5% while the rest see either a quarter-point less or more than that.

Any of those outcomes would leave the Bank of Japan -- due to meet on Thursday -- as the only other global central bank still retaining negative rate policy.

The uncertainty over the SNB reflects the difficulty in second-guessing how closely President Thomas Jordan and his colleagues want to act against inflation by shadowing the surrounding euro area, while sticking to a decision calendar with only half as many meetings. A 75 basis-point hike wouldn’t factor in more ECB moves to come.

“The SNB will come up with a more firm rate increase now so they can afford a smaller step in December,” said Maxime Botteron, an economist at Credit Suisse Group AG in Zurich. “We expect a slowdown or even a recession in the euro zone, so the window of opportunity for large rate hikes is closing.”

Botteron’s forecast of a 75 basis-point hike assumes officials will now stick to their quarterly timetable rather than reverting to their former habit of surprising investors with policy changes between meetings.

A 100 basis-point move -- as sprung by Sweden’s Riksbank on Tuesday -- is predicted by three economists. Alexander Koch, an economist at Raiffeisen Schweiz in Zurich, is among eight predicting a smaller half-point rate move, though he doesn’t exclude something bigger.

“In order not to not have to react with an intra-meeting hike in the autumn, they could choose to hike rates more strongly,” he acknowledged.

The calendar constraint brings an added complication to the challenge of directing monetary policy amid spillovers from other jurisdictions. Much of the world is already struggling with that in the wake of aggressive tightening by the US Federal Reserve, which will hike again on Wednesday.

Swiss officials have long tried to insulate their economy from the policy of their neighbors, with whom they conduct most of their trade. It was in a bid to protect exporters from gains in the franc versus the euro in 2015 that officials brought rates below zero.

The strength of the currency is a boon right now however, keeping imported price pressures at bay. Even with inflation above 3%, it remains a fraction of the euro zone’s. Meanwhile the economy is still predicted to grow, albeit with a weaker outlook than before.

The Swiss will be the last in Europe to exit negative rates after the ECB’s hike in July and Denmark’s increase this month. Sweden’s Riksbank went above zero in 2019, judging the policy’s side effects as too damaging to the financial system.

While the SNB wasn’t the first central bank to go negative this century -- that accolade goes to Denmark -- it did so most aggressively. Until June, its rate was -0.75, the world’s lowest and it now is at -0.25%.

The policy revisited an episode in the 1970s when Switzerland’s government imposed a charge on deposits held by foreigners. Jordan has described that measure as not comparable and not very effective.

While the SNB always defended the use of negative rates, it also tried to insulate its financial system from their worst effects on profitability. Exiting that stance now brings its own challenges, according to Koch at Raiffeisen.

“There is a high level of excess liquidity,” he said. “To get banks and money markets accustomed, maybe it is also advisable not to move too rapidly into the new regime.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.