Mar 25, 2020

Fed Can Turn to Peers for Tips on Pushing Loans to Business

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The Federal Reserve might want to ask its international peers for advice on how to ensure sure its attempts to support smaller businesses work out.

Central bankers in the U.K., the euro zone and Japan have spent years pushing measures to boost credit to companies, and are revamping those tools to combat the economic shock from the coronavirus pandemic. Fed policy makers joined their efforts for the first time on Monday with a pledge to create a ‘main-street business-lending program.’

“They’re all trying to do the same thing and I think they will all be somewhat effective,” said Joseph Gagnon, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and a former Fed official.

Yet the jury’s out on precisely how useful the European and Asian programs are in the longer term. Here’s how they’re designed, and what they’ve achieved.

Euro Zone

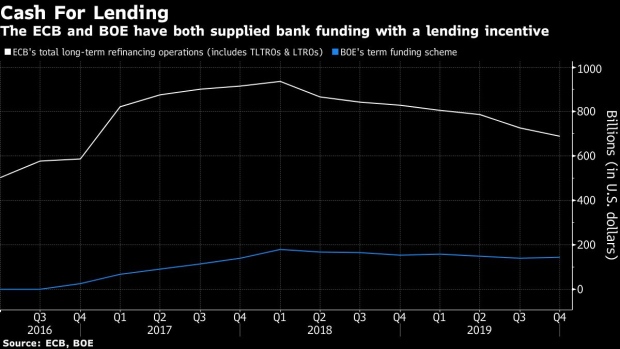

The European Central Bank has provided cheap long-term financing to commercial banks with incentives to lend it on since 2014. The approach reflects the heavy reliance of the region’s companies, particularly smaller ones, on bank loans rather than capital markets -- far more so than in the U.S.

The terms of these targeted longer-term refinancing operations have become easier over time, with banks now actually paid by the ECB -- via a negative interest rate -- to borrow the cash.

While the ECB says the policy has successfully ensured its monetary stimulus reaches companies and households, some studies suggest its effectiveness varies across the 19-nation bloc.

The higher the banking-sector concentration, the weaker the transmission of low borrowing costs, according to research by Matteo Benetton of the University of California, Berkeley, and Bank of Italy’s Davide Fantino.

A country’s economic vulnerability might also play a role. University of Lisbon’s Antonio Afonso and Bank of Portugal’s Joana Sousa-Leite found that while banks were probably using TLTRO funds to lend to the real economy, the impact was higher in less-vulnerable economies.

Ultimately, the ECB can make it easier for banks to fund smaller companies but it can’t take on all the risk, according to Piet Christiansen, chief strategist at Danske Bank.

“The ECB can deal with the liquidity side of the problem, but they can’t deal with credit risk -- commercial banks still need to take that,” he said. “The only way around that would be for governments to step in and say they won’t allow loans to default.”

U.K.

A key part of the Bank of England’s coronavirus crisis response is TFSME, under which the institution hands out four-year loans at or very close to the benchmark rate -- now 0.1% -- and offers additional funding to those that increase lending, especially to smaller firms.

It builds on something called the Term Funding Scheme that was deployed in the aftermath of Britain’s vote to leave the European Union in 2016. Azad Zangana, an economist at Schroders, says that program helped corporate lending.

“Allowing very cheap funding against a broad array of collateral to the banking system is a very helpful thing,” said David Miles, a former BOE policy maker.

The U.K. Treasury, BOE and Financial Conduct Authority wrote a letter to banks on Wednesday, urging them to keep lending amid the uncertainty.

Still, the BOE said the goal of the TFS wasn’t necessarily to increase loans, but to ensure that cuts in its benchmark rate were passed on to businesses. It also to some extent just replaced private securitization markets, according to researchers at Deloitte.

The BOE’s history of supporting smaller firms goes back even further. Its Funding for Lending Scheme, introduced in 2012, provided cheap loans to encourage banks to expand credit. Yet an OECD paper by Olena Havrylchyk, an economics professor at the Sorbonne, was unable to show whether the FLS incentives directly boosted loan growth to smaller firms.

Japan

The Bank of Japan’s latest initiative to bolster credit is an 8 trillion-yen ($72 billion) program extending yearlong, interest-free loans to banks using corporate debt as collateral.

It builds on several attempts to stimulate business activity after years of deflation. One facility helps industries with growth potential including tourism; another allows banks to borrow twice as much from the BOJ as the new loans they offer to companies.

“The BOJ lending programs have been fairly effective at keeping channels of finance open at times of crisis, and that’s one of the reasons we haven’t had a panic in lending activities in Japan,” said Masamichi Adachi, chief Japan economist at UBS Securities and a former BOJ official.

The lesson though is that it’s hard to end a program once it’s launched. Loans for banks struggling after the earthquake and tsunami in 2011, designed as a temporary program, are now permanent. A corporate-bond purchase program set up after the global financial crisis is also still around -- the upper limit on the BOJ’s holdings has just been raised to 4.2 trillion yen.

(Updates with BOE, FCA, Treasury letter in fifteenth paragraph.)

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.