Mar 3, 2021

Greensill’s Overnight Fall From Grace Was Months in the Making

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- From the outside, 2020 was bringing validation to the idea behind Lex Greensill’s financial empire.

His eponymous firm was seeking funds at a lofty valuation with the pitch that the pandemic laid bare small suppliers’ need to be paid quickly.

But by the middle of last year, two parallel sets of events were quietly threatening two of the biggest sources of funding that enabled his brand of financial disruption -- eventually bringing the firm to a breaking point.

In July, an obscure Australian insurer refused to extend policies covering the loans Greensill made, taking away the security blanket that allowed major investors like Credit Suisse Group AG getting comfortable with his courting clients below their radar. And around the same time, the German regulator BaFin started a probe into his fast-growing bank in Bremen.

At issue in both cases was the question of risk, and in BaFin’s case, the amount of it that was tied to another entrepreneur in Greensill’s inner circle, Sanjeev Gupta. He had been an early client and investor in Greensill, and the loans to Gupta’s firms fueled the growth of both men’s conglomerates.

Interviews with more than a dozen people familiar with the matter show how the twin threads unraveled rapidly this week, bringing Greensill’s firm to the verge of collapse. Started a decade ago with a promise of “making finance fairer” -- attracting backers such as SoftBank Group Corp. and advisers like former U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron -- Greensill Capital’s swift spiral now is risking thousands of jobs at borrowing companies, disrupting the supply chains of multinationals and even the U.K. healthcare system.

It has been a stunning comedown for a firm that as recently as last year was touting a valuation of $7 billion. Greensill Capital is planning to start insolvency proceedings in the U.K. as it seeks to sell its operating business to Athene Holding Ltd., the annuity seller backed by Apollo Global Management. And Germany’s financial watchdog shuttered Greensill Bank after asking law enforcement officials to investigate accounting irregularities at the lender.

Greensill, whose interest in supply-chain finance stemmed from his early years working on his family’s farm in Australia, carved a niche for himself in a fast-growing business that saw a boost in the years following the global financial crisis more than a decade ago. Banks were pulling back from lending to smaller firms, as regulations around risky lending practices grew increasingly more onerous.

Cameron, Gupta

To lawmakers eager to stimulate a recovery, supply chain finance seemed like the perfect solution. In 2012, then-Prime Minister Cameron announced a supply-chain finance program that was designed to get funding to small companies quicker. Greensill was an adviser to the U.K. government on that program, and in 2017 was anointed as a Commander of the British Empire for his services to the economy.

Greensill had started his own firm in 2011 after stints at Morgan Stanley and Citigroup Inc., later attracting $1.5 billion of investment from SoftBank Group Corp. Over the years, Greensill has also been closely linked to British-Indian businessman Gupta, the man once dubbed the “savior of steel” by the U.K. press because of his penchant to buy up moribund steel plants.

Greensill’s links to Gupta have roiled other money managers. Long-dated project finance notes tied to Gupta’s GFG Alliance and arranged by Greensill were at the center of an investigation that prompted the suspension of GAM Holding AG’s one-time star Tim Haywood in 2018.

BaFin’s Audit

BaFin last year started a forensic audit of Greensill Bank, charging KPMG with the task, after concerns emerged that too many of the assets on the bank’s books are ultimately tied to the same source: Gupta.

Gupta, a former commodities trader, heads GFG Alliance, a loose collection of entities owned by him and other family members. Much of the business, which spans steel, aluminum and renewable energy, was built at a breakneck pace that saw him spend about $6 billion over a five-year period on a series of deals and investments from Scotland to South Carolina. The targets were largely old, unwanted assets in need of significant investment.

Providing the financial firepower that drove the spree was Greensill’s eponymous firm. Gupta told Bloomberg News in October that Greensill was the company’s biggest lender.

The links between Greensill and Gupta ultimately proved to be the focus of BaFin’s probe. The KPMG probe found irregularities with how Greensill Bank booked certain assets linked to Gupta. One of the most serious findings was that the bank had booked claims for transactions that hadn’t yet occurred but which were accounted for as if they had.

“BaFin found that Greensill Bank AG was unable to provide evidence of the existence of receivables in its balance sheet that it had purchased from the GFG Alliance Group, ” according to a statement from the German regulator.

‘Extensive Advice’

Greensill said in a statement late Wednesday that it had received “extensive advice,” from law firms in the U.K. and Germany on how to classify the assets, and that it immediately complied after BaFin advised it late last year and early this year that it didn’t agree with its accounting.

“Greensill Bank has at all times been transparent with its regulators and auditors about its approach to classifying assets and the methodologies for determining such classifications,” a spokesman for the company said by email.

Pressure from BaFin was a factor that prompted Greensill to look for potential buyers for its exposure to Gupta earlier this year. One of the parties that Greensill reached out to was Credit Suisse, people familiar with the matter said.

But on the other side of the globe in Australia, separate developments were afoot. In a last-ditch effort to make its insurer extend policies that were due to lapse on March 1, Greensill took Bond and Credit Company, a unit of Tokio Marine Holding, to court. The company warned that losing $4.6 billion in insurance coverage for its 40 or so clients could spark defaults and put 50,000 jobs at risk. But late on Monday a judge in Sydney struck down Greensill’s injunction.

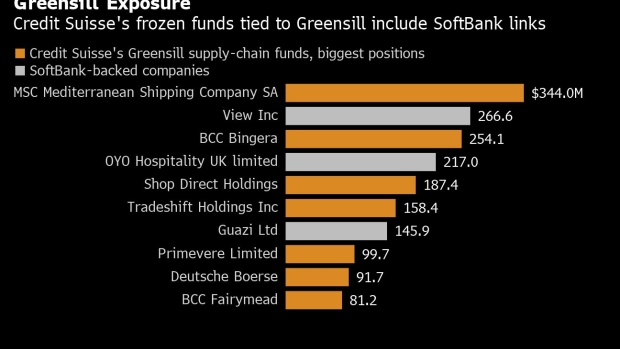

Hours later in Zurich, Credit Suisse suspended its $10 billion family of funds that invested in loans arranged by Greensill, choking off a key source of funding to the companies. The insurance lapse left some debt no longer valued on the strength of the insurer but rather on the underlying borrower, triggering questions on the valuations of the assets.

The series of events underscore a key element that underpinned Greensill’s strategy: its reliance on insurance coverage. The insurance arrangements gave firms like Greensill’s the flexibility to court smaller borrowers that wouldn’t otherwise be able to get investment-grade ratings, with a measure of security that an insurance policy brings. The impeccable credentials also allowed Credit Suisse to sell funds to investors such as pensions and corporate treasurers seeking suitable assets to help boost returns.

It’s not clear why Bond and Credit Company allowed the policies to lapse. In denying Greensill’s injunction to force the insurer to renew the contracts, the Australian judge noted that “despite the fact that the underwriters’ position was made clear eight months ago, apparently Greensill only sought legal advice about its position” in the last week of February.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.