Oct 13, 2021

Jane Fraser has a plan to remake Citigroup while tormenting rivals

, Bloomberg News

Expect a dividend increase from the U.S. banks: David Baskin

One of Citigroup Inc.’s more serendipitous real estate investments turned out to be the roof deck it built into its newly renovated downtown New York headquarters. With sweeping views of the Hudson River, it’s a thoroughly ventilated space that investment bankers and traders can slip away to for some socializing or after-hours cocktails. Not a bad perk for those back in the office in the midst of the lingering pandemic.

Kicking back at a patio table, Jane Fraser, Citigroup’s newly installed chief executive officer, is discussing one of her first wins on the job. Early in the summer, she broke with a slew of rival bank CEOs who were cajoling workers back to their old desks just as the delta variant of COVID-19 was spreading, leading to infections that eventually forced them to revise their plans yet again. She’s taken a more relaxed approach, mostly letting employees decide when they want to return. This may sound warm and fuzzy, but it’s also a weapon for recruiting and retaining talent. Her team has been fielding inquiries recently from executives looking to defect from rivals including JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

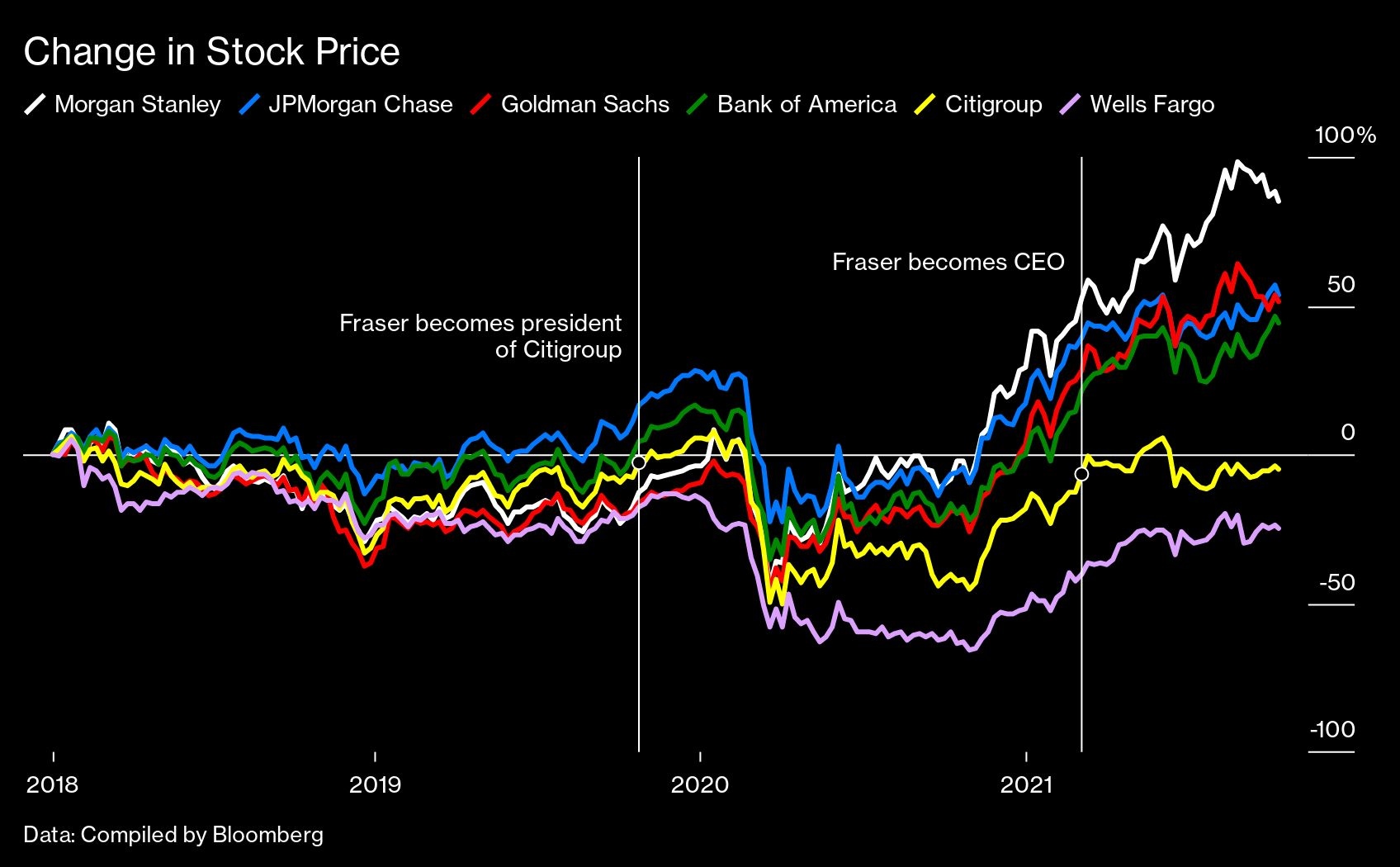

“I want to crush the competition,” Fraser says, sipping her coffee. The first woman CEO of a top U.S. bank makes it easy to forget she’s assumed one of the toughest jobs in global finance right now. Citigroup’s stock price is languishing below the levels it notched just a bit over three years ago, even as some of its U.S. competitors’ shares sit near record highs. The Scotland-born 54-year-old says she has a plan to reshape the bank, starting with its wealth management and global consumer businesses.

Fraser is trying to turn around the original banking behemoth—one investors think has grown too complicated, with the wrong mix of businesses and a lot of baggage. Although it has roots going back 210 years, the modern Citigroup was bolted together in the 1990s by Sanford “Sandy” Weill, who persuaded Congress to repeal the Depression-era law that had separated federally insured deposit-taking banks from riskier Wall Street businesses. Then, in true Titanic fashion, Citigroup showed why that’s dangerous. Slammed by losses tied to bad mortgages and other distressed holdings in 2008, it required more U.S. taxpayer support than any other bank in the financial crisis. In 2009 its stock price dipped below US$1. Even now, the shares trade 86 per centlower than 15 years ago.

Of the six major Wall Street banks, Citigroup is the only one trading for less than the net value of its assets per share, a common measure of a bank’s worth. Even so, it’s a formidable player. It operates in more than 160 countries, moves US$4 trillion in payments a day, and houses the world’s largest credit card issuer. Regulators deem it one of the three most systemically important banks on the planet, so it’s not only investors who have a stake in Fraser getting Citigroup’s house in order.

Citigroup’s problem is that it doesn’t generate profits commensurate with its size. Fraser’s predecessors had to spend much of the decade after the crisis whittling down an US$800 billion pile of bad and unwanted assets. By the late 2010s, Citigroup was “slowly but surely” catching up with its rivals in profitability, says Chris Kotowski, an analyst at Oppenheimer & Co. “Then COVID just knocked them back to square one again.” The bank’s credit card business has hindered results, for a counterintuitive reason: Thanks to government efforts to keep the economy alive, people were able to pay down balances even as lockdowns caused them to spend less. Citigroup also has a smaller branch network than JPMorgan and Bank of America, so it struggled to keep up as they soaked up deposits from consumers.

Wall Street’s gold standard for measuring how much a bank earns with every shareholder dollar, known as return on tangible common equity, was a mere 6.9 per centat Citigroup last year. JPMorgan achieved 14%. The No. 1 thing shareholders want to see, according to Fraser, is “closing the return gap with our peers and focusing more on higher-returning businesses.”

She has little room for error. The bank is in the midst of a yearslong campaign to shore up its internal systems and data programs that will end up costing it billions. Last year the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Reserve singled out Citigroup for “longstanding” failures in its risk management and controls. In addition to fining the bank US$400 million, they ordered it to take steps to fix the problems. The bank also has to seek approval from the OCC before making any acquisitions. Citigroup’s dysfunction was on display last year, when employees at the bank mistakenly sent almost US$1 billion to Revlon Inc. creditors, an error that wasn’t cited by the regulators but has resulted in a lengthy and embarrassing public court battle to recover the funds.

Like every CEO right now, Fraser also has to deal with the more immediate challenge of managing a totally disrupted workplace. The first inkling that Fraser might do that differently than other Wall Street bosses came just days after she took the job in March, when she promised that most of the bank’s staff would be able to work from home at least two days a week on a permanent basis. The news sent shock waves through Wall Street. JPMorgan’s Jamie Dimon and Goldman Sachs’s David Solomon had been turning up the volume on their desire to see all of their workers return.

Fraser didn’t stop there. She’s also letting employees rewrite their schedules. It’s fine, she says, if people want to knock off early to pick up their kids from school and log on in the evening to finish their work. “Maybe see your kids or avoid a particular time of commuting that’s hellacious,” she says. That’s a huge shift for Wall Street, known for requiring 100-hour workweeks of its junior bankers and boisterous trading floors that have historically had mostly male staff. Citigroup is essentially embarking on the industry’s first case study to see whether a completely different approach will work—for everybody. “The number of dads that came up and said, ‘It’s so neat because I can work from home and therefore I can get to the kid’s school play.’”

The bank is closely monitoring how people respond, and so far there’s no sign they’re slacking off. “You can see from the output,” Fraser says. “It’s refreshing because you get rid of some old anachronistic cultures or ways of doing things and you unleash this energy.”

One place Citigroup hopes to see some new energy is in its wealth management business. Citigroup’s sale after the financial crisis of its Smith Barney brokerage to Morgan Stanley marked one of Wall Street’s most heralded transformations—for the buyer. “It’s unfortunate they had to sell Smith Barney,” says Kotowski. The deal launched rival Morgan Stanley’s ambitious expansion into wealth management and advice for affluent individuals, giving it a stream of steady revenue and sending its stock soaring; its recent purchase of Eaton Vance Corp. for its asset management business is an attempt to bolster that bet.

Citigroup, hamstrung by the OCC’s order limiting its ability to make deals, is in no position to try to mimic that move. But as a number of global banks pursue versions of Morgan Stanley’s strategy, Fraser says she thinks they’re actually making a mistake. Their idea is to marry an asset management unit that cranks out products to a fleet of brokers or financial advisers who help sell them to clients. The problem, says Fraser, is that the industry is on the verge of sweeping changes.

“A lot of the U.S. model is very broker-driven, which I think is going to get obliterated in the years ahead,” Fraser says. Silicon Valley startups and banks alike have been rolling out virtually free trading and automated investing platforms. That’s going to make it easier for people to sift through and select their investment products. At the same time, successful teams of brokers have been defecting from their banks. Citigroup wants to position itself as a more objective counselor. “Because we don’t have an asset manager, we’re very clear that we’re there to serve our clients,” she says.

In her final months as the company’s president, just before rising to CEO, Fraser merged Citigroup’s wealth unit for retirement savers with its private bank for the ultra-rich. The combined division will lean on a pipeline of customers including those from Citigroup’s commercial bank, the unit that caters to midsize businesses. The thinking: help entrepreneurs build their companies, then work with them on tending their wealth. Maybe help them with buying up competitors, issuing bonds, or raising cash along the way. “Uber and Airbnb started off in our commercial bank in the U.S. as a client, the unicorns in Latin America and Asia started off in our commercial bank as a client,” Fraser says, referring to private companies valued at more than US$1 billion. “We’re helping those companies create that wealth in the company, and then we can help the owner.”

Some in the U.S. banking industry might snicker: Citigroup’s wealth management business isn’t nearly the biggest in its home market. But it ranks No. 3 in Asia.

If international reach is one of Citigroup’s advantages in wealth management, in the eyes of investors it presents other problems. “They have banking operations around the globe, and I think that has put a lot of pressure on efficiency,” says Jim Shanahan, an analyst at Edward Jones. “It’s difficult to run global banking operations as efficiently as it would be to run a domestic-only retail banking strategy.” That critique strikes at the heart of Citigroup’s historic identity. A sitdown with the bank’s leaders a decade ago would have meant listening—a lot—to glowing descriptions of its global might. “Name just about any country—and no other foreign bank got there first or has been there longer,” then-CEO Vikram Pandit boasted to shareholders in 2011.

Fraser has spent much of her career selling off pieces of Citigroup’s global empire—first while overseeing operations in Latin America, and now as its CEO. Currently up for bid: consumer banking operations in a dozen markets across Asia and Europe that failed to turn a profit last year. Her team is going to be “clinical and dispassionate when we’re looking at things,” she says. “We make sure that we are going to be simpler.”

Time and again, Citigroup has set targets for both cutting costs and improving results and missed them. In 2008 the company told investors it would seek to improve its efficiency ratio—a measure of how much it spends to produce a dollar of revenue—by bringing it down to 58%. It ended the first half of this year above that 13-year-old target.

Fraser has given herself and her deputies a tight deadline to show investors that things will improve. The bank recently announced it will host an investor day in March, its first in almost five years. Investor days are a chance, separate from regular quarterly earnings announcements, for companies to talk to major shareholders and make the case for their businesses. Fraser, who cut her teeth as a McKinsey & Co. consultant telling other banks what they should do, will be in her element. “Investor Day is likely to be McKinsey on steroids,” predicts Mike Mayo, an analyst at Wells Fargo & Co. and a longtime critic of Citigroup. “There’s no question in my mind that it’s going to be crisp with strategic plans, with milestones.”

But Mayo wants Fraser to go even further in remaking the bank. “What she’s done so far is more like elective outpatient procedures,” he says. “They need some more serious surgery to reconfigure Citi for the future.” For instance, Mayo wants Fraser to focus on the firm’s sprawling treasury and trade solutions business, which moves money for many of the world’s largest corporations. In an Oct. 11 note to clients, he also criticized a bonus program that could reward three of Fraser’s top lieutenants—the bank’s chief financial officer, the head of the institutional clients group, and the head of enterprise operations and technology—millions of dollars each for hitting undisclosed stock targets and goals for carrying out the bank’s “transformation” plan. The awards may amount to “extra pay to execs for just doing their job,” Mayo wrote.

Fraser seems to have little trouble attracting talent to the bank. In recent months she’s added JPMorgan’s Rob Casper as chair of the bank’s data transformation and plucked Goldman Sachs’s Erika Irish Brown to lead diversity and inclusion efforts. Brent McIntosh, a former Department of the Treasury official, will soon join as general counsel and corporate secretary, while the investment bank has added a slew of new talent including JPMorgan’s Brian Truesdale, Goldman’s Chuck Adams, and Credit Suisse Group AG’s Dhiren Shah. “She’s come with a breath of fresh air,” says Mindy Lubber, CEO of the nonprofit Ceres, which campaigns for sustainable investment. “She is open to looking at the new world.”

Even amid the pandemic, Fraser has spent much of this summer traveling, holding hundreds of meetings with employees, investors, government officials, and clients. In recent weeks she’s jetted to Kenya, Mexico, the United Kingdom, and Germany, among other places. Now she says the listening tour is over. “We’re going to craft our own path,” she says, “to be as relevant in the decades ahead as we have been globally in the past. And we’re willing to be bold to do that.” Whether that happens at the desk, over Zoom, or on the roof doesn’t matter so much.