Sep 22, 2022

Japan’s Historic Intervention Fails to Alter Forces Sapping Yen

, Bloomberg News

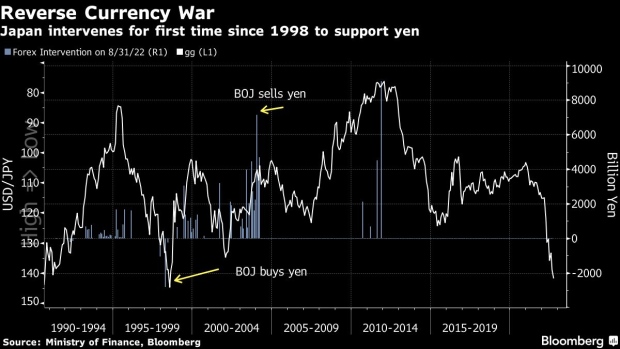

(Bloomberg) -- Japan’s first market intervention in over two decades to push up the yen halted the currency’s steady drop. What it didn’t do was alter the widening gulf in global monetary policy that’s driving the decline.

That means the impact may be relatively short-lived as long as the Bank of Japan remains a dovish holdout among the world’s central banks. The yen’s nearly 20% decline against the US dollar this year has largely resulted from its policy of holding down interest rates as others raise them aggressively in the face of inflation.

This week, the BOJ pulled even further away, reaffirming its policy of capping yields just as the Federal Reserve enacted its third straight three-quarter percentage point rate hike. Banks from Indonesia to the U.K. kept tightening policy. Switzerland did, too, putting an end to an era of negative interest rates in Europe.

The net effect has been a virtually inexorable drag on the yen as investors shift cash elsewhere to seize on interest rates well above those in Japan. And unless that changes, analysts see little odds that the currency will rebound against the US dollar.

The “intervention flies in the face of the Fed and the BOJ’s actions,” said Mark Sobel, a former US Treasury Department official who is now the US chair of the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, a think tank. “So, on balance, expect it to have a very short-term impact.”

That effect of the Ministry of Finance’s move was apparent in currency markets Thursday, where the yen surged as much as 2.6% to a little over 140 to the dollar. It had tumbled to as low as 145.90, the weakest since 1998.

Japan Intervenes to Support Yen for the First Time Since 1998

The US Treasury and the European Central Bank said they didn’t participate in the intervention. And though the finance ministry’s purchases may keep the yen trading in a range, the downward pull on the currency may strengthen if US inflation remains high and the Fed charts a more aggressive tack.

“While the intervention may not be enough, they are tapping on the break,” said Stephen Jen, the London-based chief executive of hedge fund Eurizon SLJ Capital Ltd. He said the move may hold the yen below 150. “They can slow down the market, and control the market at 145. They are showing their displeasure, despite the fact that the Fed and the BOJ are going in opposite directions.”

Historically, Japan has intervened far more often to keep the yen from strengthening too much, which poses risks to its export industries. The largest yen purchase came in April 1998 when the BOJ bought 2.8 trillion yen ($20 billion) in the foreign-exchange market.

But that didn’t immediately arrest the yen’s slide and it didn’t bottom out until that August. It started to rapidly appreciate only after Russia’s debt default and the collapse of the Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund sowed chaos in financial markets, forcing investors to unwind trades that relied on borrowing yen and investing elsewhere. By the end of December, the yen had rallied 30% against the dollar from its lows.

Unlike in 1998, however, the yen’s weakness isn’t being driven by carry-trade speculators, who borrow yen and sell it to invest the proceeds elsewhere. In fact, short bets on the yen by leveraged funds are 35% less than the level in mid-April when the yen was trading around 125 per dollar, according to the data compiled by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission.

Instead, it’s the policy divergence and Japan’s fast-deteriorating trade positions -- thanks to lofty energy prices -- that are to blame for the yen’s depreciation. In August, the trade deficit in Japan -- a net energy importer -- reached a record, meaning the country was flooding the global markets with yen to pay for goods.

Of course, the significant stockpile of reserves that Japan can use in the currency markets will likely cow any trader seeking to pile on bets against the currency. Japan had $1.17 trillion in reserves at the end of August, compared with average daily yen trading volume in Tokyo of around $479 billion.

That stockpile may be large enough to help bolster the currency until the end of the Fed’s tightening cycle, which swaps traders see coming by early- to mid-2023.

Here’s what strategists had to say:

Jens Nordvig, founder of New York-based research firm Exante Data

“We think the Ministry of finance/Bank of Japan are working to hold the dollar-yen rate below 145 for a period. But we do not think a much lower dollar-yen rate is likely to result from intervention. As such, we could be in a 140-145 range for a little while. But a hawkish Fed and weak global growth is a powerful combo to keep supporting the dollar.”

Chris Turner, head of foreign-exchange strategy at ING in London

“Clearly, investors are going to think twice about paying for USD/JPY over 145 now. And one can argue that we will now enter a volatile 140-145 trading range. But expect investors to be happy to buy dollars on dips near 140/141 knowing that Tokyo will find it impossible to turn this strong dollar tide – a tide that should keep the dollar supported through the remainder of this year.”

Steven Englander, head of Group-of-10 currency research at Standard Chartered Bank

“I think they are very satisfied so far -- market chatter doesn’t suggest they spent to much and US dollar-yen rate is down by more than 4 big figures. They caught market off stride even though everyone was discussing risk of intervention. If I were them I would rinse and repeat in NY time to see if they could get it to go under 140.”

George Saravelos, global head of FX research, Deutsche Bank

“As we have argued for a long time, it is simply not credible for a central bank to be debasing its currency via extreme amounts of QE while authorities pursue a stronger FX at the same time. When Japan last intervened to defend the currency in 1998, the US - Japan interest rate differential was moving sideways instead of sharply higher, like it is today. That the intervention has been unilateral and that it happened on the same day of a dovish Bank of Japan meeting speaks to the very large internal contradictions.”

Michael Metcalfe, head of macro strategy, State Street Global Markets

“If past intervention periods are a guide, it will likely take repeated actions to prevent further JPY weakness especially given the BOJ’s decision to leave yield curve control in place. The action will also be closely watched by other central banks, especially in Europe, where currency undervaluation in excess of 20% is making an unwelcome contribution to inflation pressures.

For the moment more co-ordinated intervention to weaken the USD is potentially inconsistent with the US authorities desire to tighten financial conditions. However, once US interest rates get to their peak early next year, it is quite possible that a less strong USD will be in all the G7’s interests; keep a close eye on bookings at the New York’s Plaza Hotel in Q1 2023.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.