Nov 4, 2022

Powell Snub Leaves Stock Bulls Facing Ruthless Valuation Math

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- With hopes dashed of a Federal Reserve reprieve, investors are being forced to do something they’ve been trying to avoid all year: assess stocks on their merits. What they’re seeing isn’t pretty.

The S&P 500 slumped 3.4% this week -- reversing about half its rally since mid-October at one point -- as Jerome Powell’s unwavering war on inflation and America’s worsening recession odds exposed a valuation backdrop that may only be resolvable through more investor pain. Climbing bond yields are exacerbating a situation where equities can be framed as anywhere from 10% to 30% too expensive based on history.

The most recent market swoon, coming after two weeks of big rallies, is an unwelcome reminder of valuations’ sway to those who just piled into stocks at one of the fastest rates this year. Last month, investors poured $58 billion of fresh money into equity-focused exchange-traded funds, the most since March, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

“We are now in round three of investors playing chicken with the Fed, and losing,” said Mike Bailey, director of research at FBB Capital Partners. “Investors now have more obstacles in their path, since the Fed is clearly on a rampage to slow the economy, while earnings are likely in the early stages of a painful 10% to 20% decline from prior peaks.”

Tempted by past years of success in dip buying, bulls haven’t given up despite repeated failures, including the most recent, which came after Fed Chair Jerome Powell again doused optimism about a dovish central bank.

Even after a massive valuation correction, stocks are far from screamingly cheap, going by past bear-market bottoms. At the low in October, the S&P 500 was trading at 17.3 times profits, exceeding trough valuations from all 11 previous drawdowns and topping the median of those by 30%.

“It’s tough to find a very strong bull case for equities,” said Charlie Ripley, senior investment strategist at Allianz Investment Management. “Obviously the Fed has done a tremendous amount of tightening already into the economy, but we really haven’t seen a marked slowdown from that policy tightening just yet. So I don’t think that we’ve seen maybe the worst of it yet.”

Of course, valuations provide a poor timing tool, and a continuing expansion in corporate profits could also, mathematically speaking, offer the route by which their excesses are cured. Yet anyone watching the trajectory of interest rates and earnings would concede that the fundamental backdrop is ominous.

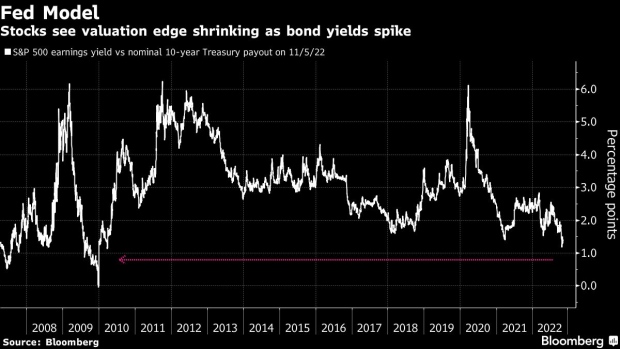

While gauging fair market value is obviously an inexact science, a technique that compares the income stream from stocks and bonds known as the Fed model gives a lens into the perils facing equity investors. By that model, the S&P 500’s earnings yield, the reciprocal of its P/E ratio, sits 1.3 percentage points above what’s offered by 10-year Treasuries, near the smallest premium since 2010.

Should 10-year yields rise to 5% from the current 4.2% -- a scenario that’s not out of question with bond traders betting the Fed will hike interest rates to above that threshold next year -- the S&P 500’s P/E ratio would need to slide to 16 from the current reading of 18, all else equal, to keep its valuation edge intact. Or profits would have to go up by 15%.

Betting on a big earnings bump like that, however, is a long shot. Going by analyst estimates, S&P 500 profits will increase 4% next year. Even that, many investors say, is too optimistic.

In a client survey conducted by Evercore ISI this week, investors expect large-cap earnings to end 2023 at an annual rate of $198 a share, or $49.50 a quarter. That’s 18% below the fourth-quarter forecast of $60.54 by analysts tracked by Bloomberg Intelligence.

In other words, what looks like a reasonably priced market may turn out to be expensive if the rosy outlook doesn’t materialize. Based on $198 a share, the S&P 500 trades at a multiple of 19.

“We’re still cautious on US equities,” said Lisa Erickson, senior vice president and head of public markets group at US Bank Wealth Management. “We are still seeing signs of growth slowing in the economy as well as in corporate earnings.”

The gloomy camp has bond investors on their side. In a growing warning over a recession, the yield on two-year Treasuries kept rising relative to the 10-year note’s this week, reaching a level of extreme inversion not seen since the early 1980s.

Navigating 2022’s market has been painful for bulls and bears alike. While the S&P 500 plunged 25% from peak to trough, reaping gains as a short seller means one had to endure seven episodes of rallies, with the largest scoring gains of 17%.

Along the way, the index has posted monthly moves of at least 7.5% in five separate months -- two up and three down. Not since 1937 has a full year experienced so many dramatic months.

The large swings reflect conflicting narratives. While manufacturing and housing data indicate an economic slowdown, a strengthening labor market points to consumer resilience. With the Fed depending on incoming data to set the agenda for monetary policy, the window of outcomes is wide open between a softening in growth and a serious contraction.

Amid the murky outlook and market turbulence, Zachary Hill, head of portfolio management at Horizon Investments, says his firm has sought safety in consumer-staple and health-care stocks.

He’s not alone in turning cautious. Money managers last month slashed equity exposure to record lows amid recession fears, while their cash holdings hit all-time highs, according to Bank of America Corp.’s latest survey.

“We’ve been that way for a while and we need to see a lot more clarity to get rid of that defensive bias,” Hill said. “We’ve been looking for more certainty from the bond market in order to feel good about what type of multiple we need to be applying to earnings in this environment.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.