Sep 27, 2022

Solar Panels Piling Up in Warehouses in Energy-Starved Europe

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Tens of thousands of solar panels are sitting unused in warehouses across Europe just as the continent struggles with an unprecedented energy crisis.

The spike in electricity prices after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is making the case for a speedier transition to renewable power. Demand for solar from households and businesses is soaring and the supply of panels is rising to meet it. But a key piece of the puzzle is missing: there aren’t enough engineers to install the rooftop modules fast enough to keep up with orders.

“Solar power is infrastructure, and you can’t just click your fingers and make infrastructure happen,” said Jenny Chase, lead solar analyst at BloombergNEF. Solar firms “are starting to realize that, actually, they are not installing as fast as they are buying.”

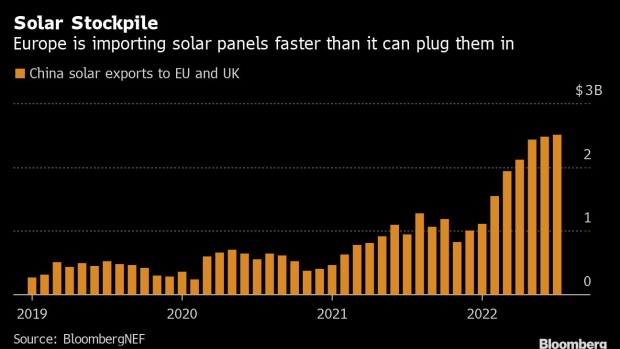

The backlog is showing up in export data from the world’s biggest producer of solar panels. China’s sales to Europe totaled $14.2 billion from January to July, or about 54 gigawatts, according to BloombergNEF. That’s enough to power more than 16 million German households, and more than the 41 gigawatts BNEF had forecast would be installed in the region over the whole of this year.

Europe is still set to install a record amount of solar capacity in 2022, but the number would be even higher if all the people clamoring for panels could actually get them, according to Dries Acke, director of Brussels-based lobby group Solar Power Europe.

“Installers in many countries are fully booked for the next weeks and months,” Acke said. For Belgium or Germany, panels ordered now might not get installed before March, he said.

The problem is that fixing solar panels to rooftops is labor-intensive. Interruptions caused by a lack of installers are much more common in the sector than for the scaled-up power plants constructed by utilities, according to Daniel Tipping, an analyst at consultancy Wood Mackenzie Ltd.

One of Spain’s biggest rooftop installers, Holaluz-Clidom SA, has started an academy to train workers to address the labor shortage. A year ago, it took about 180 days to get a rooftop system installed, but the company has now got that down to a maximum of 45 days, said Chief Executive Officer Carlota Pi Amoros.

“There’s insane demand for solar in Spain,” Pi Amoros said in an interview. “We’re entering into fall, and we assure our customers they’ll have their solar panels before winter. It’s a very strong selling point.”

Supply Chain

Labor shortages are the main bottleneck for Europe’s solar industry right now. But a pileup of panels in Rotterdam, the continent’s largest port, is also about logistics. Long delays are being reported at customs, while a global shortage of computer chips mean that some panels are missing the inverters used to process electricity.

“It’s really bad at the moment with the supply chain,” said Martin Schachinger, managing director of German solar brokerage platform pvXchange Trading GmbH. “We have no chance to reach our climate targets in the next years if this shortage delays the growth of the industry.”

China’s solar firms are alive to the risk to earnings from their biggest market in the European Union, where sales more than doubled in the first half of the year. Jinko Solar Co.’s Chief Marketing Officer Gener Miao told investors last month that demand in some European countries is expected to slow in the second half due to “problems affecting the logistics chain.”

And there’s another threat looming, albeit over the longer term. EU legislators have proposed taking the bloc’s prohibition on goods made with forced labor and expanding it to third countries. For the Chinese solar industry, it’s an unwelcome echo of the US crackdown on products manufactured in Xinjiang, a raw materials hub for much of the nation’s solar production.

Solar Giants Slump as Forced Labor Concerns Spread to Europe

The allegations of abuses against the region’s Muslim Uyghur population -- denied by China -- have soured relations between Beijing and Washington even further, disrupting shipments of the modules that are an important component of the energy transition planned by the Biden administration.

The European Commission’s proposed ban is still to be approved and in any case would probably take a couple of years before it took effect, according to Morgan Stanley analysts including Simon Lee.

“US policies relating to labor issues have resulted in delays to China’s solar shipments,” Lee said in a note. “A proposed EU policy raises similar possibilities.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.