Mar 21, 2023

Swiss Brace for Credit Suisse Bailout Costing Them $13,500 Each

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Switzerland’s tab for shoring up its reputation as a financial center could run to 12,500 Swiss francs ($13,500) for every man, woman and child in the country.

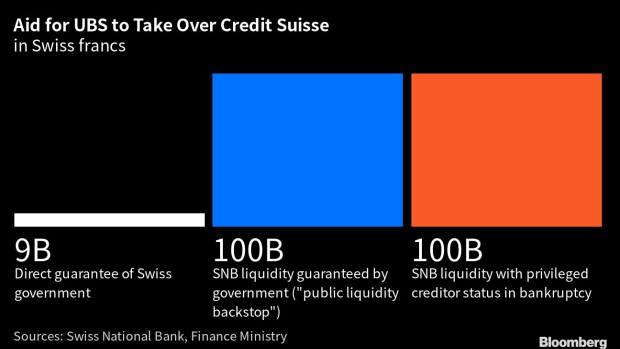

To backstop the emergency sale of Credit Suisse Group AG to its Zurich rival UBS Group AG, the Swiss government pledged to make as much as 109 billion francs available — a hefty burden for the country of 8.7 million people.

On top of that, there’s a guarantee from the Swiss National Bank of 100 billion francs that isn’t backed by a government guarantee, according to the deal announced Sunday evening.

The combined sum of 209 billion francs is equivalent to about a quarter of Switzerland’s gross domestic product and exceeds total European defense spending in 2021. The price tag for Switzerland’s largest ever corporate rescue could add up to more than three times the 60 billion-franc bailout of UBS in 2008.

The renewed rescue for well-paid bankers sparked protests. About 200 people gathered outside Credit Suisse’s headquarters in Zurich on Monday, chanting “eat the rich” and throwing eggs at the building at the heart of the city’s financial district.

“We are fed up with the idea that if you are big enough, you get everything,” said Christoph Rechsteiner, a partner at the Zurich-based tax consultancy MME. “The law is changed for you over a weekend.”

Read more: Credit Suisse’s Demise Spurs Protests in Zurich Financial Center

On top of the financial guarantees, the Swiss government agreed to change legislation that bypasses shareholder approval and the country’s financial regulator wiped out about 16 billion francs worth of Credit Suisse bonds to increase the bank’s core capital.

“The solution that has been drafted now is that if all comes good, UBS makes a huge profit,” Rechsteiner said by phone. “They got Credit Suisse for nothing at all and the government is backing the losses.”

Despite the frustration, financial experts cautioned that there’s little chance the final price tag will reach the limits set by the government, while the cost of doing nothing could have been much higher.

On the 100 billion-franc guarantee to SNB, “there I see a somewhat limited risk,” said Manuel Ammann, director of the Swiss Institute of Banking and Finance at the University of St. Gallen. “I see more risks in the 9 billion francs that the government is guaranteeing in terms of excess losses for Credit Suisse.”

The government’s SNB guarantee would be partially covered by securities and bankruptcy privileges, which should ensure that even in the worst-case scenario it would be covered without the need to tap state funds, Ammann said.

Liability for the government-backed 100 billion francs “would only materialize if there was a bankruptcy of the merged entity,” he added. “This is a real long shot at the moment.”

Bumpy Track Record

During the global financial crisis, UBS received 6 billion francs from the government and split off 54 billion francs of risky assets into a fund backed by the central bank.

While the government did impose new “too big to fail” regulation for banks after the 2008 crisis, the legislation failed to counter the steady run of scandals and management upheaval that ultimately destroyed investor trust in Credit Suisse.

Systemically relevant banks had to turn themselves into holding companies. That was supposed to facilitate a clean breakup and protect domestic retail banking operations. In theory, all other parts would have been liquidated to prevent dangers to the Swiss financial system.

But Switzerland’s government decided not to implement the legislation, and instead pushed for the merger. The evident lack of trust in its own rules could prove very costly for the image of one of the world’s premier financial centers, according to Ammann.

“Now both Swiss banks had to be saved by the government,” he said. “That’s not a good track record.”

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.