Dec 16, 2020

The future of cities: The end of the rat race will reshape Canada's urban centres

The global pandemic changed everything in 2020. Now it is going to change everything forever. This is part of "The Future of" series, in which BNN Bloomberg looks at what is next for our transformed economy and daily lives.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Max Zhu had what can only be described as a hellish commute. It started with a 10-minute drive from his Oshawa, Ont., home to the local commuter GO-Train station, then a 70-minute (if there were no delays) train ride to Toronto’s Exhibition station, and finally a 10-minute walk to the Liberty Village offices of First Capital where he works as a senior financial analyst. That’s an hour-and-a-half of travel each way from Monday to Friday — or a total of 15 hours in transit per week.

Working from home over the past nine months, Zhu says he’s been happy to have those hours back and would like to continue the arrangement post-pandemic — but only on a part-time basis. He misses the water-cooler chat and collaboration that can only take place face-to-face, but would prefer to return to the office only two or three days a week. “We had so many get-togethers and industry working groups where all this expertise could come together in one place and we could bounce ideas off each other — it was incredible,” says the 26-year-old Chartered Professional Accountant. “That made the long commute worth it.”

Zhu’s perspective reveals one of the major long-lasting changes expected to come out of the pandemic. While there’s still a need for workers to be physically present for the purposes of problem-solving and innovation, the days of everyone rushing into the city en masse at the same time each morning — only to sit in front of a computer or attend progress update meetings — are over.

- The future of money: After the pandemic, will you have your own 'financial pandemic'?

- Future of work: Business is not a zero-sum game, says OpenText CEO

- Companies will keep downtown offices to differentiate themselves: Allied Properties CEO

THE FUTURE OF...

“That’s a waste of time and energy on both the part of the employee and the employer,” says Richard Florida, a professor at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management and School of Cities, and one of the world’s leading urban theorists. “The whole idea of separating work from home, the way we did in the industrial revolution, and enduring long commutes is starting to finally at long last decline.” He expects about 20 per cent of the workforce to continue to work from home full time post-pandemic, with another 30 per cent telecommuting part of the week.

Instead of the usual rat race, people will only come into the city when it provides an experience they can’t get at home. “Just like retail has been transformed into an experience, the office will have to be transformed into an experience, in order to get people back into the office,” Florida says.

But the coming farewell to the harried commute downtown for all workers five days a week won’t only be felt within the walls of Canada’s urban workplaces. This shift will also usher in a transformation to our cities as a whole, allowing for more affordable housing, walkable neighbourhoods, multi-use public spaces and repurposed transportation routes. Here are the trends to watch.

RISE OF THE 15-MINUTE NEIGHBOURHOOD

Many urban experts, including Florida, expect the shift to working from home will reduce demand for office space in central business districts. But that could be a good thing for cities. “Many of those office towers can be turned into much-needed affordable housing,” he says. “Instead of being a 9-to-5 neighborhood, it can be a 24/7 neighbourhood.”

That sounds great to Zhu, who wouldn’t hesitate to move to Toronto if he could afford it. He likes the concept of a 15-minute neighbourhood — in which shops, restaurants and services are all within a short walk or bike ride from where residents live and work. “Where I live in Oshawa, I’d have to drive 20 minutes just to get to the gym,” he says.

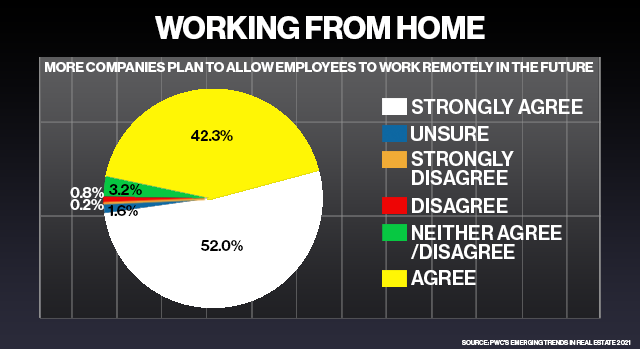

It’s still unclear, however, whether a decline in demand for urban office space will truly come to pass. According to PwC’s Emerging Trends in Real Estate 2021, there’s a fair bit of uncertainty about what commercial tenants will do long term. Some predict that everything will go back to the way it was pre-pandemic, while others expect a renewed interest in suburban office development, as some employees look to work closer to home.

That, in turn, would help create 15-minute neighbourhoods in suburbs, which have typically been a place where people live but not work. “One can see a lot of those old, abandoned office parks and malls turned into much better versions of co-worker spaces, restaurants, cafés and workout facilities,” says Florida.

Right now, however, tenants are hedging their bets by taking short-term leases on office space, says Frank Magliocco, national real estate leader at PwC Canada. Magliocco also expects there will be a structural change in the way commercial real estate is used. “Employers are going to take a hard look at their offices and ask themselves what role that space should serve going forward,” he says.

MORE COLLABORATIVE WORKPLACES

Tonya Surman, CEO of the Centre for Social Innovation, says she thinks the office of the future will resemble the co-working model her organization first brought to Canada 15 years ago, which companies like WeWork have since taken mainstream.

“Community is going to become even more important,” she says. Smaller employers, in particular, will downsize but maintain enough space so staff can come in a few times a week, hold meetings, train staff and reconnect.

“The whole idea of separating work from home, the way we did in the industrial revolution, and enduring long commutes is starting to finally at long last decline.”

Florida agrees office designs will have more of a focus on common spaces and collaboration. “The office as workspace — where you have a desk or a cubicle — will give way to the office as meeting space or interaction space,” he says, adding that there will be spaces for people to work out, do yoga or meditate, and more outdoor spaces for people to congregate.

And for those whose employer decides to go completely virtual or move to the suburbs to avoid the high cost of downtown commercial real estate, niche third-party co-working spaces such as CSI will fill the void, says Surman. Where CSI provides networking and business development opportunities for individuals who want to make the world better, other co-working spaces will become networking hubs for communities with other personal or professional interests, she says.

DEDICATED PUBLIC SPACES

An end to the rat race commute could also lead to a permanent change in the way roads are used. With less traffic coming into the city, some road space could be dedicated to bike lanes, wider sidewalks for pedestrians, or additional outdoor dining, as was the case during the pandemic.

“This could be done in a flexible manner, where the space is not permanent or fixed but reallocated depending on the day or time of day,” says Lawrence Frank, an affiliate professor at UBC's School of Community and Regional Planning and the School of Population and Public Health, and president of Urban Design 4 Health.

He even imagines a scenario in which municipalities designate specific commuting days — say, Tuesday through Thursday — and offer tax incentives to employers who demonstrate a reduction in their commuter base to maintain lower traffic levels.

“When it’s a commute day, certain streets will have to be cleared for traffic and movement of goods. On weekends, high streets could get blocked off from traffic and be set up for pedestrians and urban living. On shoulder days, maybe there would be a kind of hybrid.”

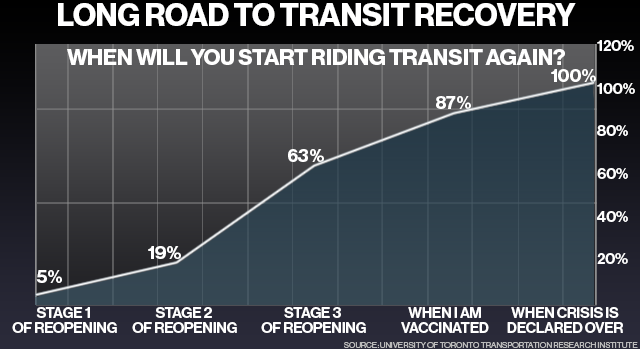

TRANSIT MOVES LOCAL

Public transit will be less about moving workers on a nine-to-five schedule from the suburbs to downtown office centres, and more about moving people between different kinds of activities within their neighbourhoods, says Florida. Even so, he expects that fears about the health risks of riding public transit will linger. “Transit will be an issue for a long time even post-vaccine,” he says.

Research by the University of Toronto Transportation Research Institute indicates a more optimistic view. In an online survey of 2,753 adults who rode public transit in Toronto at least twice a week pre-COVID, but stopped using the service during the outbreak, 87 per cent said they will come back once they’ve been vaccinated, and 100 per cent will return once the crisis is declared over. But because ridership has fallen drastically during the pandemic, public transit systems like the TTC that rely on fares for the bulk of revenue may not have the resources to return full force when riders are ready, says Frank.

“Will transit be there when the demand returns? And if service is poor — if it’s too crowded and people can’t get a seat — they might lose ridership permanently,” he says.

That, of course, would be disastrous for Zhu and others who rely on regional transit to get downtown — even if they’d only be making that commute two or three days a week.

In the meantime, Zhu is dreaming about a future when he can work in the city again — whether as a commuter or a resident — and reconnect with his colleagues and friends.