Feb 6, 2023

Trudeau eyes billions to patch Canada's creaking health system

, Bloomberg News

Millionaires still flock to Canada due to its health care and education systems: Immigration expert

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is preparing to commit billions of dollars to help shore up a strained health-care system, opening the spending taps for a service that many Canadians say isn’t working well.

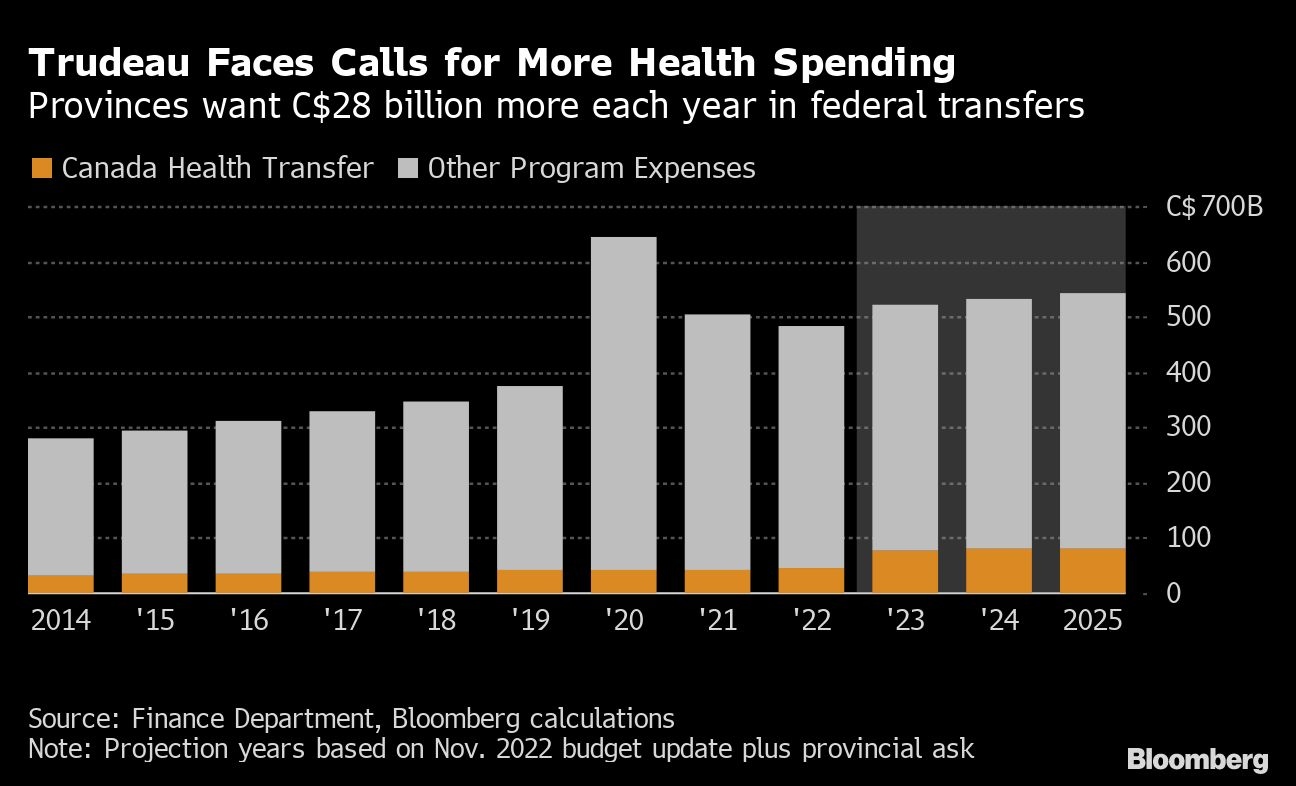

Trudeau will host provincial leaders this week in Ottawa to try to make progress on a new health funding deal. The premiers want as much as $28 billion (US$21 billion) in new annual spending. Federal officials dispute the need for that amount, and they want to place conditions on the money, such improving outcomes in long-term care.

Canada’s government-dominated medical system bears some resemblance to Britain’s National Health Service, but it’s not truly national. Most of the funding and administrative responsibility lies with the provinces, with some federal money attached. But all sides agree that it was pushed to the brink by COVID-19.

“The Canadian health-care system is at a crisis point,” said Haizhen Mou, a public policy professor at the University of Saskatchewan who studies health-care funding. “We are still living in the aftershock of the pandemic.”

Along with the backlog of surgeries and other procedures created by the pandemic, which forced hospitals to ration resources, frontline staff are burned out from the stress of the COVID crisis, she said.

Some facilities have even been forced to temporarily shut down emergency rooms for lack of staff. Family physicians are in short supply in some regions — forcing many newcomers to immigrant-friendly Canada to rely on hospital bed rental, walk-in clinics, telephone and online appointments or ER visits, for lack of an available doctor.

Trudeau and his finance minister, Chrystia Freeland, are responding to those facts. Yet they’re also hemmed in by other fiscal promises and demands — for expensive new programs like daycare, which they pledged in the 2021 election, and for subsidies or tax incentives to help industries stay competitive with the U.S. after the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act.

Major new spending is certain to prompt concerns about the government’s fiscal track, given the enormous deficits it ran up during the pandemic, which raised the ratio of federal debt to gross domestic product to about 45 per cent from 30 per cent before.

The risk of Canada’s finances becoming unsustainable was outlined last month in a report co-authored by former Bank of Canada Governor David Dodge and Robert Asselin, a long-time Trudeau adviser who’s now with the Business Council of Canada.

Dodge and Asselin concluded that, based on the government’s most recent budget update, “there is a significant risk that both the debt ratio and the interest cost ratios exceed comfortable levels over the remainder of this decade.”

Pledging more money for health care comes on top of the Liberal government’s $30 billion childcare program and a $5.3 billion dental-care plan announced last year.

The main source of existing federal funding for provincial health systems is the Canada Health Transfer, which is enshrined in legislation and grows in line with a three-year moving average of nominal GDP. In the fiscal year that began last April, the transfer rose to $45.2 billion, or 9.4 per cent of total program expenses.

But during his time in office, Trudeau has preferred to boost health funding by negotiating side deals with provinces that come with conditions attached, as opposed to simply making that main program richer.

In 2017, the government signed bilateral deals with each province that laid out details of how $11 billion in new money would be used for improving access to home and community care, along with mental-health and addiction services.

A similar process is likely to play out this time around — and the main question is how much more money Trudeau and Freeland are willing to put on the table, and if they’re willing to increase the main transfer.

The Liberal election platform in 2021 pledged roughly $25 billion over five years in new funding for various health initiatives, including for long-term care facilities and expanding access to family doctors.

If Trudeau sticks to that, new spending would be closer to the $5 billion mark annually — on top of the automatic growth in the health transfer each year. But it may take more than that to mollify the provinces.

Freeland, speaking Friday in Toronto after meeting provincial finance ministers, said the government has two big-ticket spending priorities as it prepares its next budget: health care and clean energy investment incentives.

“We do need to behave with real fiscal responsibility even as we need to make these two big investments,” she said. “And it was important for me to be candid with provincial and territorial finance ministers about that reality.”