Oct 18, 2022

Trudeau Insider Warns Inflation Hinders Fight Against Inequality

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- One of Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s longest-serving economic advisers said progressive governments need to reckon with the unequal impact of inflation, arguing it requires carefully-targeted spending.

Tyler Meredith, who left government last month after nearly seven years, warned that Canada’s 40-year-high inflation rate “hurts, most importantly, the people at the bottom end of the income distribution.” It therefore risks undermining Trudeau policies that have sought to reduce wealth inequality.

“As a progressive, I care about those things,” Meredith said during an hour-long interview last week at Bloomberg’s Ottawa bureau. He discussed Trudeau’s record, the Liberal government’s extraordinary pandemic spending, and where Canada’s economy is headed now.

“How you deal with inflation isn’t just about, ‘Do you need to enter an austerity period, to cut in order to reduce aggregate demand?’ There are ways to have a more targeted approach that helps protect people,” Meredith said.

Last month, with a new Conservative leader hounding him about the rising cost of living, Trudeau announced two measures to cushion the blow. The government temporarily doubled a sales-tax rebate for low-income earners at a cost of C$2.5 billion ($1.8 billion) and boosted a housing benefit for renters for about C$700 million. Despite the modest price tag, the Bank of Nova Scotia said the moves risk adding to price pressures.

Meredith defended the spending as precise, aimed at people who need it. He said Canadians should be paying more attention to how many provincially-controlled welfare programs aren’t automatically keeping up with rising costs, unlike federal transfers.

“It is abysmal that we have not seen more of a public debate about how to protect poor people in that context,” he said, “and why not all provinces are doing what they should be doing to ensure that the most vulnerable in society are protected.”

Pandemic Shock

Meredith, 36, served in both Trudeau’s office and at the finance department, where he was director of economic strategy and planning under Chrystia Freeland. He holds a master’s degree in public administration from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario.

After stints as a management consultant and think-tank research chief, he joined government in January 2016 and became a key architect of policy and Liberal Party campaign platforms. Asked why he left, Meredith said he needed a break after working nearly nonstop since the pandemic hit.

He said it will take time for economists to determine how much of the current spike in prices is due to governments being too slow to pull back spending, and how much is driven by global factors like the war in Ukraine. Canada’s annual inflation rate hit 8.1% in June and has since eased to 7%, with September data due Wednesday.

Canada is nonetheless coming out of the pandemic better positioned than its Group of Seven peers, Meredith argued.

It’s seen “a labor market recovery that’s one of the best in the G-7. GDP levels that were not only returned to baseline, but grew.” And Canada’s support programs, combined with comparatively strong public-health restrictions, ultimately saved lives, he added.

Still, Meredith acknowledged that many analysts -- including some within government -- are forecasting zero growth next year. Royal Bank of Canada and others are even predicting an outright recession.

“You’ve got to think about that scenario,” Meredith said, adding that the government’s playbook should incorporate lessons from the pandemic on how to support both people and businesses. Above all, the employment insurance system may need reform to ensure its coverage extends to “all of the places in the labor market where you may get hit.”

In the run-up to the 2015 election, Trudeau criticized then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper for having the worst growth record since the Great Depression. But seven years into his mandate, the Liberal prime minister’s performance -- with growth averaging about 1.6% -- has been just as anemic. And he could wind up doing worse than Harper should the economy slip into recession.

The relationship between Trudeau’s team and corporate Canada has also been fraught, with some business leaders worried the government isn’t devoting serious attention to fixing the nation’s long-term competitiveness problem.

Meredith, who advised Freeland’s predecessor, Bill Morneau, before the former finance minister’s departure in 2020, conceded that Trudeau’s growth agenda was hampered by a commodities recession that was underway when the Liberals were elected and lasted into early 2017. Three years later, the pandemic upended government planning.

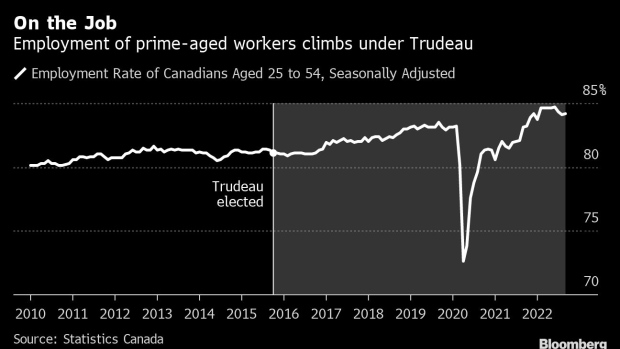

But Meredith pointed to Trudeau’s record on labor-force participation as a major accomplishment, with a rise in the employment rate among workers between 25 and 54 years old. The rate had flat-lined during the previous nine years under Harper.

The policy adviser said the employment gains have “increasingly gone to groups traditionally underrepresented in the labor market: low income people, people of color, Indigenous people, people with disabilities.”

When Canadians think about the economy, Meredith said, “they don’t think of growth as nominal GDP, or even real GDP. They think of: ‘Do I have a job? Does the job pay well enough?’”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.